In Ecuador, an historic environmental initiative to save the Yasuní rainforest and a landmark class action lawsuit against the Chevron Oil Company for environmental damages recently found their fates potentially intertwined.

In early December, the Ecuadoran government announced that its initial $100 million goal for the Yasuní project had been met. Under a novel scheme launched by leftist president Rafael Correa in 2007, the government has pledged to leave close to a billion barrels of crude under the ground indefinitely in this Amazonian paradise, in exchange for receiving $3.6 billion—50% of the oil’s market value—from wealthy nations and corporations. The donated funds, to be held in trust by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and fully contributed by 2024, will be earmarked for renewable energy and sustainable development initiatives, as well as social programs in Ecuador’s impoverished Amazon region. Credit: World Resources Institute

Credit: World Resources Institute

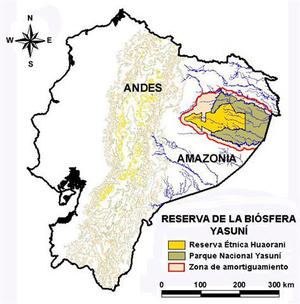

Located at the intersection of the Amazon rainforest, the Andean mountains, and the equator, the 3,800 square mile Yasuní National Park is one of the world’s most biodiverse regions. A designated World Biosphere Reserve, it is also home to two native communities living in voluntary isolation.

In addition to preserving unique flora, fauna, and indigenous cultures, saving Yasuní will prevent the release of some 400 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. According to the government, the Yasuní initiative represents a “paradigm change towards a post-fossil fuel model of development,” which will help Ecuador transition from an extractive economy based on oil exports to a new strategy based on sustainability.

The Yasuní plan has been widely praised as an innovative approach to reducing carbon emissions, promoted by statesmen and celebrities such as Desmond Tutu, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Leonardo DiCaprio. But the worsening global economic crisis and shifting global climate politics have taken their toll on potential contributions.

Last summer, Correa announced that the project was on the verge of failing, with only $40 million raised—primarily through a debt-swap agreement with Italy. Countries like Germany announced their reluctance to donate to forest protection without the benefit of carbon offset credits—a market-based approach widely criticized by climate justice groups for commodifying the rainforest while allowing polluters to continue degrading the environment. In contrast, the Yasuní model is based on the principle that wealthy nations and corporations owe a climate debt to countries like Ecuador that should not be compensated through carbon markets.

Meanwhile, Correa warned that a Chinese company was poised to move ahead with oil drilling in Yasuní if a $100 million “downpayment” on the project could not be raised by year’s end. Critics accused him of “environmental blackmail” and of sending mixed messages that served to undermine his own initiative. Some noted the government’s duplicity in proposing to save Yasuní while promoting oil exploration elsewhere in the Amazon, as well as pipeline and highway construction projects that threaten to displace indigenous residents from areas adjacent to the park.

Chevron protestor carries oily waste to courthouse. Credit: Firgs.Understandably, the announcement that Yasuní’s initial deadline had been met was greeted by environmental groups with some surprise and skepticism, including accusations of “creative accounting.” Suspicions deepened when the activist group Amazon Watch charged that Chevron Oil had offered to “bail out” the initiative with a $500 million contribution (matched by an equal amount for environmental clean-up)—if the Ecuadoran government would arrange to dismiss a landmark legal case in which Chevron has been found liable for $18 billion in environmental damages.

Chevron protestor carries oily waste to courthouse. Credit: Firgs.Understandably, the announcement that Yasuní’s initial deadline had been met was greeted by environmental groups with some surprise and skepticism, including accusations of “creative accounting.” Suspicions deepened when the activist group Amazon Watch charged that Chevron Oil had offered to “bail out” the initiative with a $500 million contribution (matched by an equal amount for environmental clean-up)—if the Ecuadoran government would arrange to dismiss a landmark legal case in which Chevron has been found liable for $18 billion in environmental damages.

In this precedent-setting class action litigation, 30,000 indigenous Ecuadoran farmers and residents have sued Chevron—the second largest U.S. oil conglomerate—for environmental damage caused when Texaco, its predecessor company, dumped billions of gallons of toxic waste in their communities more than 30 years ago. The story was memorialized in the documentary film “Crude.”

Chevron lost the case last February in Ecuador, but has sought to block enforcement of the judgment through international arbitration in The Hague and in U.S. courts. Chevron’s legal position was considerably weakened last September, when a U.S. appeals court unfroze the $18 billion award—the largest environmental judgment in history. Just this week, the award was upheld by an Ecuadoran appeals court. Chevron has vowed to continue to fight the ruling.

While there’s no evidence that the Ecuadoran government seriously considered Chevron’s proposal, Amazon Watch says that Ivonne Baki, Ecuador’s former U.S. ambassador who now coordinates the Yasuní initiative, was actively “shopping” the deal in an effort to salvage Yasuní. Says Pablo Fajardo, lead attorney for the Chevron plaintiffs, “Chevron and Baki think Ecuadoran officials are still running a banana republic government willing to sacrifice the rights of their own citizens for a small bribe.”

“We’re not about to give Chevron a get-out-of-jail-free card by donating to the Yasuní,” says Esperanza Martinez, an Ecuadoran environmental activist. “Ecuador is not interested in Chevron’s blood money.”

On December 30, Baki reaffirmed that nearly $117 million has been raised for Yasuní, keeping the project alive (without any contributions from Chevron). The full list of donors is not yet available on the project website. Another $580 million must be pledged by the end of 2013.

The Yasuní fund is now open to individual donors. It’s too late for 2011, but for those seeking a head start on 2012, tax-free contributions for as little as $1 can be made here.

Read more from Emily Achtenberg’s blog, Rebel Currents. See also “The Chevron-Texaco Judgement: A Triumph of Humanity,” by Alberto Acosta, in the March/April 2011 NACLA Report. Or subscribe to NACLA.