On October 6, Bolivian President Evo Morales signed a new construction contract for the first segment of a controversial highway that would bisect the TIPNIS Indigenous Territory and National Park, ramping up the stakes in the conflict as indigenous resistance and community divisions continue.

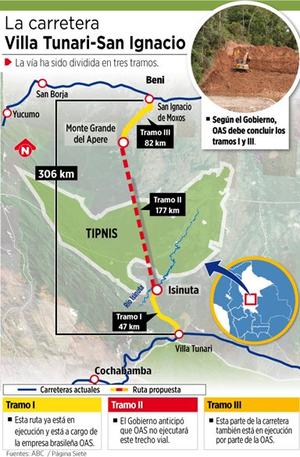

3 segments of original OAS contract. Credit: Página Siete.The contract covers the 28-mile road segment leading to the park’s southern border, one of three sections comprising the original highway contract with Brazilian company OAS (see map). Construction on this segment was halted last April when Morales revoked the entire contract, leading Brazil to withdraw its $332 million loan covering 80% of the $415 million project.

3 segments of original OAS contract. Credit: Página Siete.The contract covers the 28-mile road segment leading to the park’s southern border, one of three sections comprising the original highway contract with Brazilian company OAS (see map). Construction on this segment was halted last April when Morales revoked the entire contract, leading Brazil to withdraw its $332 million loan covering 80% of the $415 million project.

While the cancellation was officially justified on the grounds of construction delays and other irregularities, it also lent an image of legitimacy to the government’s community consultation process, which is required (by the Bolivian constitution and international law) to take place prior to any decision or action advancing the road. The consultation process, which began last July and is scheduled to end December 7, covers only the middle portion of the road that would divide the indigenous territory.

The new $32.5 million contract was awarded without a competitive solicitation to EBC, a state-owned contractor, and AMVI, a community enterprise owned by three cocalero union federations. Funding will be provided from the federal Treasury.

According to the government, the no-bid contract was justified by the need to complete OAS’s unfinished work before the rainy season and by AMVI’s unique experience with regional construction issues. For lowland indigenous groups who oppose the road, it’s just another example of government support for the pro-road cocalero sector (as well as a conflict of interest for Morales, who remains as president of the cocalero union federations).

The new contract ups the ante in the TIPNIS conflict as indigenous resistance, to both the consultation process and its apparent results, continues. The government insists that it has consulted 48 of 69 communities in the TIPNIS, with 47 approving the road, providing a strong two-thirds mandate. TIPNIS leaders dispute these results, citing their own surveys showing that 52 communities reject both the road and the consulta. Ongoing resistance, including river blockades centered in the community of Gundonovia, has paralyzed the consulta in the park’s northeast section. In San Ramoncito, located near the center of the park, a consulta brigade arriving by helicopter was prevented from entering the community.

As the consulta lurches towards its official deadline, the government has struggled with different end-game strategies for dealing with the resistance. Earlier this month, Morales announced that it was “no longer important” to complete the consulta, since the government’s 2/3 mandate would be “sufficient.” Senate president Gabriela Montaño concurred that the government can’t force dissenting communities to be consulted. Credit: La Razón.

Credit: La Razón.

However, the TIPNIS consulta law requires all mojeño, chimán, and yuracaré communities within the territory to be consulted. Accordingly, government officials proposed to relocate the consulta, along with any members of the dissenting communities who wished to participate, to the city of Trinidad, outside the TIPNIS. Vice President Alvaro García Linera cited the example of war-torn Colombia as proof that ample international precedent exists for this strategy.

After this plan was informally nixed by members of the Supreme Electoral Court, the government proposed to implement the consulta between the hours of 10 p.m. and 4 a.m. in dissenting communities. At least two such consultations were reportedly carried out, with no indication of the level of participation achieved. Most recently, the government has announced that it will require dissenting communities to complete a form, validated by all community members, evidencing their rejection of the consulta.

The government has also used judicial, legal, and economic pressures in an effort to discourage the resistance. Initially, officials blamed “outside agitators” for the blockades and attempted to expel at least 10 foreigners (who said they were tourists). More recently, judicial action has been threatened against indigenous leaders and allied NGOs for obstructing the consulta and allegedly blocking the delivery of food and medicine to TIPNIS communities (which indigenous leaders vehemently deny).

Community licenses for cacao production and caiman hunting have recently been suspended, in line with the government’s position that the territory’s current “intangible” status precludes community development initiatives, along with construction of the highway. Importantly, the government has not used force or police intervention to dislodge the resistance.

As evidence of the extraordinary degree of distrust and polarization that now exists within the TIPNIS, the government has acknowledged that at least 40 communities have refused to cooperate with preliminary mapping activities for the decennial census. Lowland indigenous groups fear that the census will be used to audit and revert their communally-held lands, for redistribution to migrant farmer-settlers. The quest for more productive land by these highland indigenous “colonists” —who are major supporters of the TIPNIS road and the Morales government—and their resentment of “unproductive” native landholdings (used primarily for hunting, fishing, and food-gathering)—is a major underlying issue behind the TIPNIS conflict.

Indigenous deputy Pedro Nuni. Credit: Página Siete. The government has responded that communities not counted in the census will lose their rights to health, education, and other services. Aymará sociologist Pablo Mamani has commented that the government may stand to lose as much as the communities from this harsh verdict. The state’s inability to carry out the census, he argues, demonstrates an absolute loss of sovereignty in these 40 communities, representing 3 indigenous people—an “unwillingness of the populace to be governed.” In Mamani’s view, these communities are in a virtual “state of war” against the government, while the government has declared a form of “plurinational apartheid.”

Indigenous deputy Pedro Nuni. Credit: Página Siete. The government has responded that communities not counted in the census will lose their rights to health, education, and other services. Aymará sociologist Pablo Mamani has commented that the government may stand to lose as much as the communities from this harsh verdict. The state’s inability to carry out the census, he argues, demonstrates an absolute loss of sovereignty in these 40 communities, representing 3 indigenous people—an “unwillingness of the populace to be governed.” In Mamani’s view, these communities are in a virtual “state of war” against the government, while the government has declared a form of “plurinational apartheid.”

To further cement this rupture, indigenous organizations in the Beni department (where part of the TIPNIS is located) have decided to field their own candidate in the upcoming gubernatorial election. Pedro Nuni, an indigenous deputy elected on the MAS (Moving Towards Socialism) government party ticket, but now a MAS dissident and a leader of the two TIPNIS marches will run against MAS candidate Jessica Jordan (a former beauty queen) and at least two opposition party candidates. This marks a significant departure from lowland indigenous groups’ traditional political support for the MAS.

While lowland indigenous leaders say they will not ally with opposition parties in Beni, they have also signaled that Beni is a rehearsal for the 2014 presidential elections.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s weekly blog Rebel Currents, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).