This piece was published in the Summer 2013 issue of the NACLA Report.

The passing of Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez on March 5 was a great blow to Venezuelans in the Bolivarian process, but particularly to women, who have been some of the major beneficiaries of Venezuela’s social programs and legislation over the last 14 years.

Article 88 of the 1999 Venezuelan Constitution recognizes work in the home as a contribution to the economy, making housewives available for social security benefits. As a result, by 2010, over 200,000 women had benefited from the government Mothers From the Barrio Mission, which provides financial support, job training, and sexual education to poor women living in the slums of Venezuela.1

Through the government Robinson and Sucre Missions, hundreds of thousands of low-income Venezuelans have learned to read and write, graduated high school, and studied at the university. Under the Housing Mission, over 370,000 homes have been constructed and distributed to low-income families over the last two years.2 The Baby Jesus Mission has helped to reduce infant mortality to a rate of 13 per 1,000 live births by improving hospital infrastructure and increasing the availability of medicine.3 The Children of Venezuela Mission now provides monthly stipends to low-income pregnant mothers, adolescents, and families with handicapped children.

In recent years, several laws have been promoted by women’s movements and passed by the Venezuelan National Assembly. The 2007 Law on the Women’s Right to a Life Free from Violence describes violence against women as a human rights crime, and outlines the government’s responsibility to guarantee women’s rights. The responsible paternity law, passed the same year, recognizes fathers’ rights, particularly paternity leave. Venezuela’s new Labor Law went into effect on May 7, guaranteeing the right to work for both women and people with disabilities, and pensions for all Venezuelans, including full time mothers. It also increased maternity leave to six months and gave the same right to parents who adopt a child under three years of age.4

All of these steps, as well as the government’s creation of a National Women’s Institute and a Ministry of Women’s Affairs, have been particularly important for Venezuelan women who are disproportionately affected by poverty. According to Alba Carosio, Co-Founder of the Center for Women’s Studies at the Central University of Venezuela, 70% of those in poverty are women, and the majority of poor households have women at the head of the family.5

Perhaps this is part of the reason that women have played such a substantial role in the Bolivarian process. Seventy percent of the people participating in the Venezuela government missions are women.6 And they are at the heart of the communal councils, the committees, various grassroots movements, and feminist collectives working across the country. Despite all of this, machismo, patriarchy, and individualism maintain a powerful grip over the country.

Yanahir Reyes is a young Venezuelan feminist and activist from the Caracas barrio of Caricuao. She is a founder of the feminist radio program Millennium Women’s Word on the Caracas community radio station Radio Perola and she worked for many years with Women’s First Steps, a community group in the low-income Caracas barrio of la Pedrera that focused on empowering women through education and action. She currently works as a community educator for children and families for the National Institute for Nutrition, but, as she says, “always with a gender vision.” This interview took place on April 17.

MF: In terms of violence against women, what is the situation like in Venezuela? Did it improve under Chávez? And what is the role of women’s organizations in combating it?

YR: This is definitely one of the legacies that our comandante left. Women from the feminist struggle have effectively brought to light the importance of dismantling a patriarchal system. One of the greatest achievements of this legacy is the passage of the new Labor Law, in which, above all, the woman worker, the mother, was defended. But, effectively, in this [revolutionary] process is where women have been able to win back their native place, being respected in language and in practice. The violence has lessened over time. I have felt that there is a new sensibility. Violence against women is talked about a little more, promoting a new masculinity, one that helps maintain better relations of equality among men and women. But at the same time, we still have problems of violence, of sexism maintained by the mainstream media. Even though we have won laws that protect women workers, students, mothers, it is culturally still a structural problem, and change comes much more slowly. This can be seen in elections, because nothing is isolated. You can see this now in our defeat in the elections—I call it a defeat, because although we have a president and we won, the revolution is in danger because of a structural cultural problem. This is a sign that there is still a cultural rejection of a profound transformation. So there is still much to do so that we can really see more equal relations between men and women in daily life. And above all for the women who are mothers, who are responsible for their children. Although they are successful, it’s not fair that they have to bear all the responsibility. Transformation is occurring, but the comandante was also the space that made the feminists’ struggles even more visible.

MF: What does Chávez’s death mean for women in the Bolivarian process?

MF: What does Chávez’s death mean for women in the Bolivarian process?

YR: For us women, we lost a great brother who listened to us, who had humane sensitivity, so humane that he had the capacity to heed the needs of women. Women have been crying, now, over the loss of a brother, son, husband, a comrade. As I read it, Chávez redeemed the father that many never had, as well as the human relation among men. Chávez broke with a paradigm and built a beautiful relationship with his brothers of Latin America, with Correa, his affection for Fidel, and a relationship that was so close with Evo Morales. He reclaimed that necessary masculinity, which in its turn demonstrated our comandante’s feminine side. I would have liked to have seen it in the 2013–19 National Plan, which Chávez wrote before he passed, that this is an anti-imperialist and anti-patriarchal country, but it does not appear. However, in practice, in his sensitivity, he was strengthening another point of view, another relationship between men and with masculinity, and he left a great void. Many women cried as if they had lost their life partner, as if he had been the father we never had, because this is a country of single mothers, of abandoned sons and daughters. This is the feeling, that we had been left orphans by this compañero. And of course all the victories that our comandante bore were a great burden and we now feel we must take on this responsibility, but with him we felt there was a guarantee of continuity. So it’s been very difficult for women and very significant for children.

MF: He also called himself a feminist.

YR: I think it was very brave of him to call himself a feminist, and on top of that, all of the social policy that was focused on liberating women. From Mothers From the Barrio to the Children of Venezuela, the most recent mission. The literacy campaign through Robinson Mission, which has also helped people graduate from high school, and Sucre Mission, which is made up of almost 90% women, who are studying in the university. And although we haven’t had 50% representation in politics, women are participating in different political spaces. As I told you, he left us a wide, ready-made path, to continue constructing and consolidating equal relations. You’re there every day working to create a new consciousness. Clearly Chávez benefitted women more than anyone else.

MF: What has been women’s role in transforming the country?

YR: I think the construction of communal councils has been an effort on the part of women. Apart from the communal councils, women have been at the heart of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela itself. The different laws’ humanist vision has been another gigantic contribution of women. The woman who is working every day in the community for the good of her family, this is fundamental for the transformation of the country. These are the people I call the silent heroines, who at one time were made invisible but can now be seen. In fact, in the most recent elections the majority of the people involved in the campaign were women, defending the political process and you saw them on TV and they spoke with such clarity and passion that characterizes women, of defending their dreams, of defending their rights as women, which they are not going to lose. Each day, women are creating a very important transformative process. In the area of nutrition, which I am now involved in and which has to do with people assuming political responsibility for their diet, women take leadership. The issues of nutrition, education, and grassroots work all have a woman’s face; the transformation and revolution have a woman’s face.

MF: Has the participation of women changed the family structure in one way or another?

YR: Well, that is difficult to say. It’s difficult to tell you mathematically that this has changed substantially. I believe it has, speaking from my own experience. I think one of the advances is that there is an important self-esteem. That is one of the first steps, recognizing the visibility of women. This has helped women develop a different attitude. The majority didn’t feel this self-esteem, and their oppression had become normal. But I feel that women today have more self-esteem, more strength. They are familiar with this topic of rights, and this helps them change their relationships, to reconfigure the traditional role of woman, even reclaiming, more than the traditional role, the role that is imposed. They have reclaimed it. Cooking, child rearing, have been some spaces that have been dignified. They are no longer spaces of oppression, but of liberation. This is important to recognize. Thanks to the advances that we have won, women have a new way of doing things and a new way of thinking.

MF: What kinds of movements have come about with the Bolivarian process, and how have they been organized?

YR: There are new collectives. I come from a very interesting one called First Steps, which was born in a community with many difficulties. Even President Chávez himself was in the community calling on people to protect their lives, giving them refuge from the rains and floodwaters that threatened families. This is a community that the president himself dignified by providing them with housing though Misión Vivienda, and the group of women from the collective, which I belonged to, have all gone through a transformation. They now have a different way of thinking, they have prospered, and they have their apartments. It is also important to highlight that from the moment Chávez came to power, he worked to provide housing for people living in precarious situations. Chávez worked even harder in the last years on housing, particularly through the Housing Mission. So this collective of women is also evidence that through organization and women’s solidarity, you can achieve many things. One of the most important things is confidence, confidence among us as women. This helps break machismo and establishes another mindset of relating among women.

There is also a great women’s movement under way. One of the most well-known is the Feminist Spider, which is one of the movements that brings together diverse women’s collectives and a diversity of genders at the national level. Of course, in these last months, the movement has shown its support for the Bolivarian process, before the historical and political situation that we find ourselves in. And new movements are emerging all of the time. A little while ago, I found out about a movement called Rebellious Skirts, which is also a group of young people who are struggling for an anti-patriarchal society and putting the decriminalization of abortion on the table and the political agenda. The grassroots collectives are working toward this and other taboo issues.

MF: And what has been these grassroots collectives’ style of organizing? How spontaneous has their political and cultural vision been?

YR: There is spontaneity everywhere, in the different forms and trenches of struggle. For example, I am now taking a course on humanizing pregnancy, labor, and birth, where there are different compañeras who work in different areas: one works in media, one is a dancer, another is a physical therapist, another is a mother. Together, we are trying to learn in order to unite, and we are forming a collective to fight to put birth in debate: How should labor be? How should it be newly empowering for woman and not for the technocracy of medicine? And we are working to see what we can do. This is going on all over Venezuela in different forms and in different trenches, in the cultural realm, in education, liberated education, of course. And this is going to continue, for sure. I see it and live it every day.

MF: In general, did the collectives feel supported by the Chávez government, and can you speak to the specific ways that Chávez helped women in Venezuela?

YR: It’s a complex relationship. Yes, there has been support and great victories. The most concrete for the grassroots collectives was the recognition of lengthening the time that women workers could spend with their newborns. This has been one of the concrete policies that have been generated by the feminist grassroots movements. As well as the Law on the Women’s Right to a Life Free from Violence, the law of responsible paternity, and the promotion of breastfeeding. But, nevertheless, the relationship between the state, power, and feminist struggles is still very tense. Some things have been accomplished and others have not, because a deep, structural, and cultural clash is still affecting relations. Yes, there have been concrete government policies that have come from above that have benefited women, like the one I mentioned to you, Children of Venezuela, which is to support the children of single mothers, not just Mothers From the Barrio, which directs money at women but also at the children. Also, mothers with disabled children have been given priority, so that now there is a new term, “functional diversity,” which is used to refer to children with some physical or mental difficulty. And Children of Venezuela has responded to this.

There is also the Baby Jesus Mission, which is for newborns and women who have recently given birth. These are profound missions, but which advance slowly, because there are other priorities on the political agenda—and above all in the last months. We had the electoral campaign, the comandante died, and the situation we find ourselves in now. But I definitely think that as soon as we have the strength, we will continue advancing. The government continues to work, the collectives continue working, there is stability, but now the state is alert, in a tense and very important moment. We are even trying to comprehend the possibility of the loss of our political power, of control of the state and the central government.

But all the same, I think the struggle is there, on the table, and it is as important as other issues, like that of gender diversity which is also still on the agenda, and for which much work needs to be done. That is why it is important to ensure this process continues. To be able to materialize this whole group of necessities of equality and justice in relations and consciousness of our Venezuelan people and our Latin American people too.

MF: Speaking of feminist activists, did they feel at any time constricted by the necessity to follow the Chavista line?

YR: There are always tensions and differences of opinion, but right now I think that it’s more about unity. Right now I think we feminists are more focused on being efficient in what we have, in what we are achieving. For women to feel protected, to feel recognized we have to keep fighting. It is a very hard internal fight, but always recognizing that this is the space where we can achieve it, not in a different form of government. In another form of government it would be impossible; it would not exist. That is why we defend the process with our lives.

MF: For women, what has been the weakness or the need that has not been achieved yet during the process?

YR: One that is very important is the legalization of abortion. Under Venezuelan law, abortion is still a crime, it is still not seen as a matter of public health or of protecting women. This is one of the issues. There is a wing of the government that is very Catholic and has stalled the creation of spaces where we could discuss this openly and come to some concrete legal decisions. This is one of the priorities on feminist agendas, among other important ones, for example the need to increase and further develop public education, in culture, the need to speak of gender and gender equality. Among other important things we need to take Madres de Barrio to the next level, so that it is not just a financial grant. And we need to continue to develop people’s consciousness. And here you have the latest electoral results. With all of the benefits that have been given and that have benefited women, a house, the economic support, the redemption of women, and yet many people have voted against Chavismo and the revolutionary process. This means they didn’t understand the message. This, I think, is one of the fundamental things that the feminist movement has not been able to achieve. The demands have largely been material.

1. Carlos Martinez, Michael Fox, and JoJo Farrell, Venezuela Speaks! Voices From the Grassroots (PM Press, 2010), 73.

2. AVN, “Gran Misión Vivienda Venezuela entrega casa número 7.005 en Yaracuy,” April 3, 2013.

3. The Guardian (UK) “How did Venezuela change under Hugo Chávez?,” March 6, 2013.

4. Ryan Mallett-Outtrim, “ ‘Part of the Transition to Socialism’: Venezuela’s Labour Law Comes into Effect,” Venezuelanalysis.com, May 10, 2013.

5. Ibid.

6. Sujatha Fernandes, “Barrio Women and Popular Politics in Chávez’s Venezuela,” Latin American Politics & Society 49, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 97-127.

Michael Fox is a former editor of NACLA Report on the Americas and a member of the NACLA Multimedia Team. He is most–recently the co-author of the new book Latin America’s Turbulent Transitions: The Future of 21st Century Socialism (Zed Books, 2013). Transcribed by Laura Casas; translated by Pablo Morales.

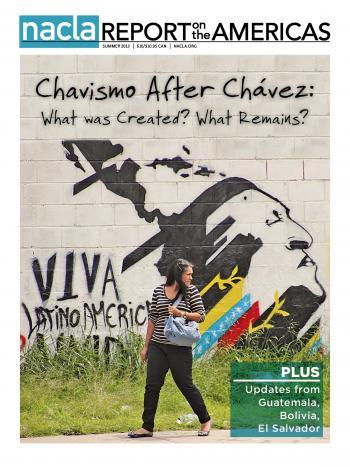

Read the rest of NACLA’s Summer 2013 issue: “Chavismo After Chávez: What Was Created? What Remains?”