The coup d’etat by General Augusto Pinochet in Chile on September 11, 1973 transformed the history of socialism. Almost a thousand days before, Salvador Allende and the Popular Unity coalition had taken office promising a “Chilean Road to Socialism” based on democratic principles. The government launched an agrarian reform program, recognized the right of workers to take over factories and run them collectively, took control of most of the country’s banks, and expropriated multinational corporations like Kennecott and ITT, all within the framework of the Chilean constitution.

From the start most of the Chilean business clans backed by the U.S. government and the multinational corporations moved to undermine and destroy this experiment in democratic socialism. As Richard Nixon’s national security adviser Henry Kissinger declared: “I don’t see why we need to stand idly by and watch a country go Communist due to the irresponsibility of its own people.” By mid-1973 it was clear to many in Chile, including myself, that the democratic institutions would not hold as the opposition began to openly call on the military to violently overthrow the government. On the left, some argued that the existing constitutional system and many democratic liberties had to be suspended and that it was necessary for workers and the popular classes to unite with loyalist sectors of the military to establish a new political regime. (1)

But one man, Salvador Allende, refused to violate the democratic institutions that brought him and the Popular Unity coalition to power. He was caught in a bitter dilemma: If he seized power and ruled by decree he would be violating the democratic principles he believed in, and yet, by not abandoning those principles he risked subjecting the country to rule by reactionary forces and the destruction of the nascent socialist society.

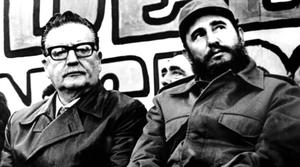

Authentic democratic socialism died with Allende in La Moneda, the presidential palace of Chile. His quest for a peaceful democratic transition to socialism proved to be a contradiction in terms. The overthrow of the Popular Unity government meant there was no viable alternative to the existing state socialist model delineated by the Soviet Union. And in Latin America progressive governments like those in Argentina and Uruguay fell under the sway of right wing repressive regimes, joining Brazil where the military had seized power in 1964. Cuba once again stood alone in the Americas. Fidel Castro had been infatuated by the Chilean road to socialism, spending 25 days there on a state visit in late 1971, exchanging views and holding conversations about the different paths to socialism. After the coup, Cuba was compelled to rely even more on the Soviet Union and the Eastern European bloc nations for its survival.

Out of the ashes of defeat, a concept of a different world began to take hold. In Chile a human rights movement emerged that drew broad support from diverse sectors of Chilean society. It soon forged a network with international human rights organizations, including many in other countries that were also confronting brutal dictatorships. The rise of the human rights movement proved to be a harbinger of a new global movement that would sink deep roots in civil society over the coming decades.(2)

In Nicaragua where the Somoza family had ruled for decades, the human rights movement took root as the Sandinista Front for National Liberation (FSLN) fought a guerrilla war against the regime. President Jimmy Carter, who assumed office in 1977 proclaiming that human rights was the “soul” of his administration’s foreign policy, tried to negotiate a transition that would preserve Somocismo without Somoza. This meant that the regime’s structures, particularly the military would remain intact. But Anastascio Somoza refused to abandon power, and Carter was compelled to suspend military and economic assistance to the regime.

On July 19, 1979, less than six years after the fall of Allende, the FSLN marched into Managua as Somoza fled the country from his private airport. The Chilean experience was very much in the minds of the new revolutionary leadership. Militants of the MIR, the Left Revolutionary Movement of Chile, had fought in the southern front with FSLN combatants led by Humberto Ortega. Now in power, it was clear that Somoza’s army, the National Guard, had to be abolished, as the FSLN constructed the Sandinista Popular Army.

Other lessons were drawn from the Chilean experience. Hoping to garner multi-class support, the Sandinistas formed a broad front government, the Junta of National Reconstruction, that included business interests that had opposed Somoza. The platform of the Sandinistas also called for a mixed economy. There would be no rapid transition to a socialist economy as private enterprise would co-exist with a state sector.

Like the Popular Unity government of Salvador Allende, the Sandinistas were committed to democratic rule. In 1984 open elections were held that the Sandinistas resoundingly won with Daniel Ortega becoming president. But as in Chile, the U.S. government, now with Ronald Reagan as president, refused to accept the results. Even before the elections, the CIA had begun recruiting elements of Somoza’s National Guard to wage a war against the Sandinistas.

The “Contras”, as they were called, did not win a major victory nor did they occupy a significant population center. But they did inflict enormous pain and suffering on the Nicaraguan people, often inflicting atrocities on remote villages. The war also devastated the economy, and it became increasingly similar to Chile’s under Allende as the business class turned against the government, hyper-inflation took hold, and there were shortages of basic commodities from toilet paper to rice and light bulbs.

By 1989, the Sandinistas faced an impasse. The Contras had largely been defeated on the battlefield, but the Reagan administration continued to support them and there was no end in sight for the low-grade, protracted war of attrition. Daniel Ortega, in an effort to secure peace, engaged in negotiations with other Central American nations and ultimately with the Contras that led to early elections in 1990.

On February 25, the day of balloting, I flew to Managua, expecting to celebrate a victory with my friends who had fought so hard for the Sandinista revolution for the past decade. We were shocked when the results rolled in. Violeta Barrios de Chamorro defeated Daniel Ortega with 54% of the vote. The next day as I was sitting in front of a friend’s house a woman vendor selling tamales passed by sobbing. I asked her what was wrong, and she said, “Daniel will no longer be my president.” After exchanging a few more words, I queried her about who she had voted for: She replied, “Violeta, because I want my son in the Sandinista army to come home alive.” She understood better than any political analyst that if the Sandinistas remained in power, the United States would continue to inflict destruction on Nicaragua in one form or another.

The Sandinista electoral defeat concurred with the collapse of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the dismantling of the Soviet Union in 1991. State socialism was crumbling. Cuba found itself isolated in the hemisphere and devoid of its international allies. The country entered a “special period” of severe economic austerity. In this void, neoliberalism, the economic doctrine that had first been implanted in Chile under Pinochet, consolidated its hold on Latin America.

In March 1990, Pinochet, after loosing a plebiscite on his continued rule, turned the presidential sash over to Patricio Aylwin, a Christian Democrat who was part of a political coalition called the Concertación. In 1973 Aylwin had supported the coup. Socialism was not on the agenda as the Concertación made a pact with Pinochet that allowed him to remain in command of the armed forces until 1998, whereupon he would become a senator for life. Just as important, neoliberalism remained the economic doctrine of the country.

Wherever one looked, socialism was moribund. But history often brings forth new unexpected social actors in the most desperate moments. A wave of social movements and organizations led by peasants and indigenous groups emerged in the rural areas of Latin America as state socialism was collapsing. By the mid-1990s they had assumed the lead in challenging the neoliberal order, particularly in Ecuador, Mexico, Bolivia, and Brazil. These new organizations were generally more democratic and participatory than the class-based organizations that traditional Marxist political parties had set up in rural areas in previous decades.

As the 1990s drew to a close and the new millennium opened, social struggles and popular rebellions erupted primarily in the cities, but often overlapping with existing rural-based struggles. The urban organizations varied greatly, some with a distinct class basis and others having a multi-class composition.

Starting in 1999 with Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, a string of left-leaning governments came to power in Latin America. These governments largely owed their ascendancy to the social movements. For the first time since the 1980s the discussion of socialism began to enter the public discourse. On January 30, 2005 Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez addressed the fifth annual gathering of the World Social Forum, declaring: “It is necessary to transcend capitalism…through socialism, true socialism with equality and justice.”(3) The roaring crowd of 15,000 at the Gigantinho stadium in Porto Alegre, Brazil heard Chávez go on to say: “We have to re-invent socialism. It can’t be the kind of socialism that we saw in the Soviet Union, but it will emerge as we develop new systems that are built on cooperation, not competition.” This marked what many refer to as the inception of what Chávez called “twenty-first century socialism.”

In Ecuador and Bolivia the socialist banner began to unfurl. The quest for socialism is now most advanced politically and economically in Venezuela, while in Ecuador the concept of socialism is only infrequently raised in public discourse, owing in part to the wide breach between the social movements and Correa’s self-proclaimed citizens’ revolution. Bolivia occupies a middle ground in which innovative discussions are taking place within and between the government and social movements that relate socialism to the indigenous concept of buen vivir.

Twenty-first century socialism is an inextricable part of the history that flows from the Popular Unity government of Salvador Allende. It inspired and informed the leaders who govern today. Like Allende, they are deeply committed to democratic procedures. During the 14 years of Hugo Chávez’s presidency there were 16 elections or referendums, while during the seven years of Evo Morales there have been seven, and during Rafael Correa’s six years there have also been seven. They have also learned from the Chilean experience the importance of opening up the legal system by convening constituent assemblies to draft new constitutions that reflect the popular interests of their societies rather than those of the traditional oligarchs and elites.

The Chilean popular movement is in turn learning from these new experiments in socialism. As the Chilean magazine Punto Final editorializes in its special edition on the 40th anniversary of the coup: “Only a democratic constitution, the product of a constituent assembly approved by the people will permit us to retake the path of liberation that was interrupted when La Moneda went up in flames.”(4) In reference to the Concertación politicians who opportunistically governed the country for two decades under Pinochet’s constitution, the editorial declares: “President Salvador Allende Gossens bequeathed the Chilean left a lesson of being consequential and personally moral that should not be forgotten.” It adds, these values are essential “for the advance of a socialist and democratic left that wants to construct a society based on citizen participation, social justice, and the integration of the peoples of Latin America.” Allende’s heroic stand will inspire those who aspire to a new socialist utopia for generations to come.

1. This article draws on my experiences in Chile from 1971-73 as well as my book. The Pinochet Affair: State Terrorism and Global Justice. London: Zed Books,, 2003.

2. NACLA was part of this movement, producing a number of studies and reports on the Chilean dictatorship and the human rights movement in Latin America. See for example Amalia Bertoli, Roger Burbach, David Hathaway, Robert High, and Eugene Kelly, “Carter and the Generals.” NACLA Report on the Americas, Vol. 13, No.2, March/April, 1979.

3. Cleto A. Sojo, “Venezuela’s Chávez closes World Social Forum with call to transcend capitalism.” Venezuela Analysis, 31 January, 2005. venezuelanalysis.coBurbm/print/907.

4. “Allende y su Leccion.” Punto Final, Edition No. 789 6 September – 26 September, 2013. Www.puntofinal.cl

Roger Burbach is the director of the Center for the Study of the Americas (CENSA) based in Berkeley, CA. He is the co-author with Michael Fox and Fred Fuentes of: Latin America’s Turbulent Transitions: The Future of Twenty-First-Century Socialism, Zed Books, London, 2013. See: www.futuresocialism.org