Photo credit: GrufidesPeru is a mining conflict country. In September of this year, the Defensoría del Pueblo (National Ombudsman Office) reported 223 social conflicts in September alone, with more than two thirds of them linked to minerals. The report also registers 196 dead and 2,369 injured in disputes over natural resources from 2006 to 2011. The database of the Latin American Observatory of Mining Conflicts (OCMAL) registers 34 cases across Peru. Even though the State has increased its presence in some mining areas and has its own Social Conflict Administration Office, the front line often becomes the ugliest side of corporate-community relations.

Photo credit: GrufidesPeru is a mining conflict country. In September of this year, the Defensoría del Pueblo (National Ombudsman Office) reported 223 social conflicts in September alone, with more than two thirds of them linked to minerals. The report also registers 196 dead and 2,369 injured in disputes over natural resources from 2006 to 2011. The database of the Latin American Observatory of Mining Conflicts (OCMAL) registers 34 cases across Peru. Even though the State has increased its presence in some mining areas and has its own Social Conflict Administration Office, the front line often becomes the ugliest side of corporate-community relations.

Hard Partners

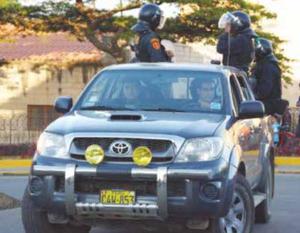

A report published this month by Peruvian NGOs Grufides, Derechos Humanos Sin Fronteras (Human Rights without Borders), the Coordinadora Nacional de Derechos Humanos (National Coordinator for Human Rights, CNDDHH), and the Society for Threatened Peoples (STP) of Switzerland, revealed that mining corporations have signed agreements with the National Police to secure their assets. Titled “Police in the Pay of Mining Companies,” the report examined the links between the police and mining corporations Antamina, Gold Fields, Sulliden Gold, Xstrata Tintaya, Minera Coimolache, and Yanacocha. These agreements allow them to request permanent police presence or ask for rapid deployment of larger units to prevent or repress social protests. In some cases, the companies provide full financial and logistical support: an incentive to use force.

Expanding Giant

The Switzerland-based commodities giant Glencore Xstrata owns the Tintaya mine and its expansion Antapaccay. Protesters in the province of Espinar have accused the company of causing pollution. As the protests grew, police moved in: three people were killed and around one hundred were injured. In a typical “knee jerk” reaction, the government of Ollanta Humala suspended freedom of assembly and imposed a state of emergency. What then? In an unusual display of force, the police arrested the mayor leading the protest against Xstrata. Dozens of riot police carrying plastic shields stormed the municipal building to pull Óscar Mollohuanca out.

Far away, indignant voters in the relaxed Swiss town of Hedingen decided to donate to charity some US$120,700 of taxes paid by Glencore Xstrata Chief Executive Ivan Glasenberg in protest against the commodities trader’s business practices.

On the Payroll

Early this year, the report “Policía mercenaria” (mercenary police) released in April by the combative newspaper Hildebrandt en sus trece, reported that in normal conditions, mining companies pay around S/.48 a day (US$10) to the official in charge, and S/.28 a day (US$10) to sub officials, for providing protection to the corporation. In circumstances denoted as “special,” the pay can be as high as S/.78 a day (US$28). Mar Pérez from the CNDDHH says that these agreements put all the responsibility for the repression of the protests in the hands of the police. “If someone dies,” she notes, “it is much harder to investigate the crime.”

Photo credit: Hildebrandt en sus trece

Photo credit: Hildebrandt en sus trece

Police corruption is not just a mining issue. In fact, it was one of the main issues in last week’s Lima political agenda when a scandal broke out involving the police protection of Óscar Lopez Meneses, former intelligence officer under house arrest. Meneses was a member of the inner circle and in the 1990s was a close advisor to Vladimiro Montesinos, chief of intelligence under dictator Alberto Fujimori who is now serving a 25-year prison sentence. In response, José de Echave, Director of Lima-based NGO Cooperacción, wrote: “the fact that a fundamental body of the State such as the National Police should take the side of those who pay them, instead of the side of the public…reveals that it does not care about public interest in the least.”

Keepers of the Lakes

The Conga mining project is located some 73 km northeast of the city of Cajamarca, in the discricts of Sorochuco and Huasmín. It has been the site of anti-mining protests for years. The U.S.-based Newmont Mining Corp. proposes to dig the Chailhuagón and Perol pits and at least two other additional areas. A plant with the capacity to process 92,000 tons of rock a day would produce 3.1 billion pounds of copper and 11.6 million ounces of gold in 20 years. However, the mineral content is very low: each ton contains less than 1 gram of gold and 0.2% of copper.

The Regional Government and the local communities denounced the serious impacts the project would have on the watersheds. To the complaints about the destruction of the Azul, Perol, Mala, and Chica Andean lakes, Minera Yanacocha replied that it would build three reservoirs to replace them. In July 2011, Denver-based Newmont Mining and its local partner Buenaventura publicly announced that they had approved funding for the project to the value of US$4800 million, one of the biggest mining investments in the history of Peru. In Cajamarca, the same mining companies have operated Yanacocha, the largest open-pit goldmine in South America, for the past 19 years.

But in November 2011, a massive strike forced them to suspend all activities. In December, Humala decreed a 60-day state of emergency in the provinces of Cajamarca, Hualgayoc, Celendín, and Contumazá. In the first days of July 2012, brutal police repression of demonstrators protesting to defend their lakes left a tragic toll of five dead and around 150 injured. In response, the communities have organized an admirable form of protests: the guardianes de las lagunas (keepers of the lakes).

Private Security Agencies

Luis Escarcena Ishikawa is the Securitas coordinator for Canadian corporation Hudbay Minerals. He was Alberto Fujimori´s aide-de-camp and one of the three pilots of the “narco-plane,” the Peruvian Air Force detained minutes before leaving for Russia with 170 Kg (375lbs) of cocaine in May 1996. According to a report by IDL Reporteros, Fujimori himself exculpated Escarcena in a public speech in July 1997.

Hudbay bought Norsemont Mining and its Constancia copper project near the Tintaya mine in 2011. Some 40% of the construction of the mine has already been completed. Authorities of the Chamaca community have expressed their concerns about the project’s “huge enviornmental impacts and reduced economic benefits.” Tito Cruz Llacma, from the local organization Frente Único de Defensa de los Intereses de Chamaca (United Front in Defense of the Chamaca’s Interests, FUDICH) stated that “it’s going to be like Espinar, where cattle and agriculture have been affected by contamination of the rivers.”

Congressional Investigation

Private security firm Forza was investigated in 2009, when a Congressional commission opened an inquiry into whether crimes were committed by the police and private security personnel in response to protests. Peruvian prosecutors accused the police of torturing protesters at the Rio Blanco mining camp in 2005, but cleared the security firm. At the time, Monterrico Metals operated the Rio Blanco project. When the scandal erupted, Forza’s press office referred Reuters to Switzerland’s Securitas, which later officially bought the Peruvian company in 2007. After the Monterrico affair, China’s Zijin bought the project in 2007. Monterrico was sued by 33 of the victims in a UK court and in 2011 agreed to pay them compensation.

Surviving the Pierina Mine

On September 19, 2012 at 3:30 p.m., about 100 protesters from the Marinayoc Community, a close neighbor of Barrick Gold Corporation’s Pierina gold and silver mine in Huaraz, gathered at the mine’s main gate known as Bravo 22. They demanded that the Toronto-based gold miner fulfill its promise to provide the community with fresh and clean water, as the massive open pit and its infrastructure had destroyed their water sources. While they were protesting at the gate, the police sent by Barrick fired tear gas bombs. The protestors dispersed down the hill while being chased by shotguns. Nemesio Poma Rosales (55) was wounded and later died. Barrick released his body to the local morgue the next day in Jangas, the district capital. According to Lima-based newspaper La República, “Edith Poma denounced that her father Nemesio was taken alive to the mine medical post where he bled to death.”

When the police started shooting, many of the protesters ran away. Alejandro Tomás Rosales Chávez (45) had made it some 20 steps down the hill when he was wounded in his back by bullet splinters. Alejandro was then taken to a clinic in Huaraz where, after three operations, the doctors saved his life. I took his testimony for this year’s edition of Barrick Gold alternative annual report. A day after the violence at Pierina, Human Rights Watch issued an open letter to President Ollanta Humala expressing concern over the use of lethal force deployed during protests. Barrick financed the restoration of the house where César Vallejo, the canonical Latin American poet, spent his childhood. The stated goals of the project were to strengthen regional pride in the rich cultural heritage of La Libertad and to improve the local economy through an expansion of the tourist industry; the money came from the Lagunas Norte mine in La Libertad, located some 150 km from Pierina.

Luis Manuel Claps studied Communications at the Buenos Aires University. He has followed mining in Latin America since 2004 as editor of the Mines and Communities Website. He is based in Lima, Perú.