June 5 marked five years since the bloodshed in Bagua, in the Amazon of Peru. Five years ago, indigenous groups such as the Awajun and Wampis staged numerous protests after the Peruvian government negotiated a Free Trade Agreement with the United States that gave mining corporations special rights to access the Amazon for oil. Then-President Alan García declared a state of emergency and sent in the Peruvian National Police to stop the protests. At least 33 people were killed, including members of both the police and indigenous groups. Although some politicians resigned their posts, like the Prime Minister Yehude Simon, no politicians have been prosecuted for being the intellectual executors of the crime.

Many Peruvians now view both the police and the Awajun and Wampis peoples as victims of a game in which the players cared and continue to care much more for the benefit of transnationals and their own pockets than the lives of “second class citizens,” as Alan García defined them.

This year on June 7, different organizations and the general public gathered at the Plaza San Martín in the evening to execute an asalto cultural, or cultural assault. Street art and paintings featured the faces of indigenous protestors and politicians seen as perpetrators of these crimes, highlighting the bond between human rights activists and artists. While witnessing this colorful and charged event, I had a conversation with William Soberón, an investigative journalist who travelled to Bagua right after the events to carry out a 21-day investigation. Soberón quoted Noam Chomsky when he spoke to me emphatically about the importance of alternative media in grassroots organizing, such as these cultural assaults, in breaking the cerco mediático, or mediatic fence, put up by powerful media corporations through the use of such outlets as Facebook, YouTube, blogs, and AM radio programs.

As we walked through the filled Plaza, Soberón and I began talking about television and the popular media that manipulate people into a state of ignorant numbness. He mentioned meeting young people who are disoriented, who want information. “Here is where they find it, in the alternative media.”

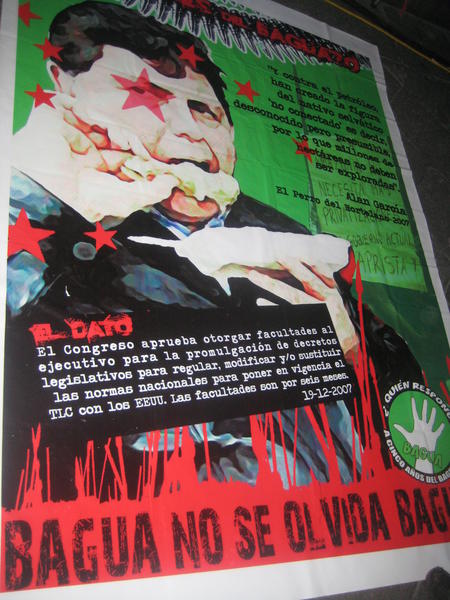

Here is Alan García, depicted as an emperor, washing his hands of indigenous blood.

Here is Alan García, depicted as an emperor, washing his hands of indigenous blood.

“Five years after, we’re still roaring.”

“Five years after, we’re still roaring.”

Most if not all indigenous protesters on June 5, 2009, defended themselves and their land with spears.

Most if not all indigenous protesters on June 5, 2009, defended themselves and their land with spears.

“We are all Bagua.”

“We are all Bagua.”

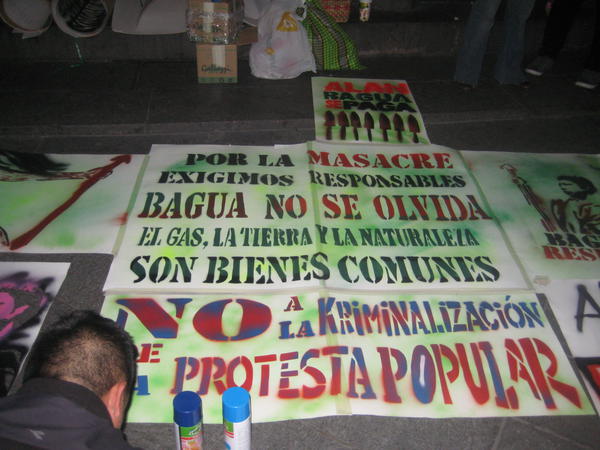

“We demand to know who is responsible.” Many people now view both the police and the indigenous people involved as victims.

“We demand to know who is responsible.” Many people now view both the police and the indigenous people involved as victims.

Five years after the Baguazo, they want to punish the indigenous leaders with life in prison. Alan García remains unscathed.

Five years after the Baguazo, they want to punish the indigenous leaders with life in prison. Alan García remains unscathed.

Silk-screening activities. The t-shirts read “Todos Somos Bagua” (We Are All Bagua).

Silk-screening activities. The t-shirts read “Todos Somos Bagua” (We Are All Bagua).

“Congress approves granting special powers to the executive… in order to activate the FTA with the United States” Alan García

“Congress approves granting special powers to the executive… in order to activate the FTA with the United States” Alan García

“Sharpen Your Spear. Defend Your Land.”

“Sharpen Your Spear. Defend Your Land.”

Constanza Ontaneda is a student in the Master’s of Latin American and Carribean Studies program at NYU. She was born in New Delhi and has lived most of her life in between Peru and the United States. Her current research focuses on race, ethnicity, and food sovereignty in Peru. She is particularly interested in Quechua-speaking rural-to-urban emigrate populations in Lima, Peru.