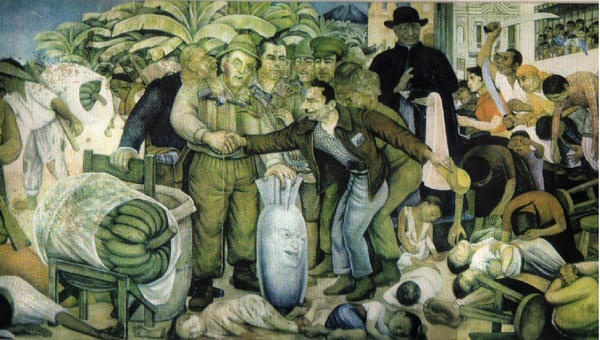

Diego Rivera’s mockingly titled “Glorious Victory” depicts the 1954 CIA coup in Guatemala (elycefeliz / Creative Commons)

Diego Rivera’s mockingly titled “Glorious Victory” depicts the 1954 CIA coup in Guatemala (elycefeliz / Creative Commons)

Before dying of pneumonia at a Guatemala hospital in late May, the recently deported 21-year-old Gustavo Antonio Vásquez Chaj told his family that the U.S. Border Patrol had kept him, at some point, wet, stripped of a layer of clothing, and in a cold cell during several days in detention. Gustavo’s travel companion, Maximiliano Tucux Chiché, 19, survived but was hospitalized in critical condition at the time of Gustavo’s death. The young men left Chicuá, their community near the city of Quetzaltenango, in late April, hoping to reach Washington, D.C., where a relative of Vásquez’s has lived for 12 years.

The tragic journey of Vásquez Chaj and Tucux Chiché is one story among many of how harmful U.S. political and economic policies in Latin America violently intersect with a hardening and brutal system of U.S. immigration control. In their case, the young men’s voyage was first and foremost one of necessity rather than of choice. Vásquez Chaj and Tucux Chiché were economic migrants fleeing a country of wreck and ruin that decades of harmful U.S. foreign and economic policies have helped to bring about. In order to “improve their quality of life,” the youths traveled northward “in search of the American dream”, wrote the Guatemalan newspaper El Quetzalteco.

This is the ultimate reason migrants from Central America have been crossing into the United States in increasing numbers in recent months. Harsh immigration enforcement policies, such as the ones that the Obama administration is currently championing, add insult to injury as the United States punishes migrants when they arrive, when it should be paying people like those of Guatemala massive reparations.

It is indisputable that the United States shares significant responsibility for the genocide of tens of thousands of Guatemalans—mainly indigenous Mayans, including members of Gustavo and Maximiliano’s community, who comprised a majority of the (at least) 150,000 killed in the 1980s alone. A 1999 UN Truth Commission blamed Guatemalan state forces for 93 percent of the atrocities. That same year, former President Bill Clinton admitted the wrongness of U.S. support for Guatemalan state violence.

U.S. culpability for Guatemala’s plight endures to this day. The problem—then and now—is that the United States is in denial as a nation over what to do about its complicity.

Just ask Bill Clinton. The day of his remorseful words in Guatemala City, he looked genocide survivors in the face, acknowledged that Washington enabled their suffering, and then rejected their impassioned pleas for U.S. immigration reform because, he said, “we must enforce our laws.” Today, many in Guatemala continue to call on the U.S. for reform measures like temporary protected status. And still, U.S. officials meet them with silence or dismissal.

Meaningful forms of justice and accountability would have a long reach. They would provide restitution to Guatemalan youth like Gustavo and Maximiliano, who are carrying the burden of genocide from their parents’ generation. True accountability would also address, among many other cases, the 16,472 DREAM-ers who have listed Guatemala as their country of origin when they registered for President Obama’s 2012 deferred action program (DACA). Moreover, justice and accountability would lead to fundamental changes in U.S. policies toward the Guatemalan state.

Instead, Washington offers programs such as the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), a $496 million endeavor since 2008 to train and assist local security forces to counter, among other perceived threats, “border security deficiencies.” Along with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the US Southern and Northern Commands, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the Bureau for Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) have all expanded activities in the region under the auspices of the war on drugs, gangs, and other criminal activity.

The U.S. formally cut off military aid to Guatemala in 1977, though U.S. funding flowed at normal levels through the early 1980s and Guatemala enjoyed enormous military support, by proxy, through U.S. client states such as Israel, Taiwan, and South Africa.

All in all, U.S. militarization in Guatemala has altered only in wording, shifting predominantly from anti-communist to currently anti-drug and counter-terror rhetoric. The policy trend continues through the present day, spanning across the Guatemalan boundary with Mexico as the “new southern border” of the United States, in the words of Chief Diplomatic Officer for DHS Alan Bersin.

The official U.S. position on supporting Guatemalan military activities is that it “was wrong” in the past, and is no longer permissible to support Guatemalan militarization except in relation to “homeland security.” In other words, Washington exercises the “doublethink” practice of “holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them,” to quote George Orwell.

So what next? Recognizing guilt is a crucial first step. Even more important is what comes after that recognition. Relevant here, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described the function of a “guilt complex” in the U.S. conscience regarding past and ongoing abuses. In a 1957 interview with NBC, King remarked: “Psychologists would say that a guilt complex can lead to two reactions. One is acceptance and the desire to change. The other reaction is to indulge in more of the very thing that you have the sense of guilt about.”

Recognition of U.S. guilt over the Guatemalan genocide should translate into concrete forms of remedial action which, to the degree possible, corresponds with the scope of the crime.

Such U.S. actions should range from radical immigration reform to extensive reparations in Guatemala, to individual and institutional accountability in rampant abuse cases like those which took the life of Vásquez Chaj and threatened the life of Tucux Chiché. Both men’s deportation and hospitalization have left their families in severe debt, according to a source I interviewed.

The treatment of these individuals and many others is emblematic of a long history of U.S. abuse of the Guatemalan people. Ending such deaths—and the ongoing influx of Guatemalans across the U.S.-Mexico divide—requires not only a recognition of that abuse but some sort of substantial restitution.

As U.S. policies remain unchanged, migrants will continue to travel northward as a necessary means of decent survival. This is a major reality of Guatemalan life. As Vásquez Chaj’s mother, told the Guatemalan newspaper Prensa Libre, U.S. treatment against her son and his companion was unfair since they were “not criminals and only sought the welfare of their families.”

This blog post has been amended to reflect the following corrections: The post previously stated Gustavo Antonio Vásquez Chaj and Maximiliano Tucux Chiché were both 20 years old, and that they were naked while locked in a cold cell during detention. In a recent interview, a source close to the author who interviewed one of the boy’s families confirmed that Gustavo is 21 years old and Maximiliano is 19 years old, and that both were stripped of some clothing but were not fully naked.

Gabriel M. Schivone is from Tucson, AZ, and has worked as a humanitarian volunteer in the Mexico-U.S. borderlands for more than five years. His articles have is appeared in The Arizona Daily Star, The Arizona Republic, the UK Guardian, McClatchy newspapers, The Chicago Tribune and others. He is currently working on a book manuscript about the history of U.S. foreign policy towards Guatemala and its relation to current United States immigration issues. You can follow Gabriel on twitter @GSchivone.