As Bolivia’s election campaign moves into full swing ahead of the scheduled October 12 vote, President Evo Morales’s controversial plan to build a highway linking the country’s Andean and Amazonian regions has resurfaced. Last week, Senator Julio Salazar of the ruling MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) party confirmed that the on-again, off-again road  TIPNIS march arrives in La Paz, October 2011 (La Razón; used with permission).that would bisect the TIPNIS indigenous territory and national park is indeed slated for construction between 2015 and 2020, according to the party’s recent electoral manifesto—optimistically entitled “Juntos Vamos Bien Para Vivir Bien” (“Working Together To Live Well”).

TIPNIS march arrives in La Paz, October 2011 (La Razón; used with permission).that would bisect the TIPNIS indigenous territory and national park is indeed slated for construction between 2015 and 2020, according to the party’s recent electoral manifesto—optimistically entitled “Juntos Vamos Bien Para Vivir Bien” (“Working Together To Live Well”).

The announcement adds a new twist to the ongoing TIPNIS saga—the most divisive conflict of Morales’s nine-year tenure (see Emily Achtenberg in NACLA’s Summer 2013 Report)—as Morales seeks his third presidential term. Pitting pro-road campesino and cocalero sectors (the traditional bastions of MAS support) against lowland indigenous groups seeking to defend their ancestral lands, the conflict has ruptured the alliance among five national social movements that originally brought Morales to power in 2005. It has profoundly altered Bolivia’s political landscape, while exposing the challenges and contradictions of protecting indigenous and environmental rights in an extractive, developmentalist economy that prioritizes territorial integration.

Despite these broad ramifications, the TIPNIS highway itself has not been a prominent feature of the electoral campaign to date. In April 2013, Morales announced that the road would be “on hold” until extreme poverty in the TIPNIS is eliminated, an anticipated three-year strategy that appeared to defuse the conflict until after the election. Subsequently, both Morales and Vice President Alvaro García Linera publicly acknowledged their misgivings about the political viability (but not the geopolitical merits) of the highway project, and the government’s flawed process for community consultation.

“We have rejected construction of the highway; it’s not going to happen—at least for another 20, 50, or 100 years,” said García Linera in Argentina in June 2013. Despite the favorable results of the consulta, he acknowledged, the government’s failure to solicit community input until after-the-fact (of securing both Brazilian financing and a contract with Brazilian firm OAS to build the road) was a grave error, creating a national rift that will take decades to heal. “We didn’t have the ability to explain [our position], to listen, to bring about consensus…community by community, ayllu by ayllu, family by family,” he lamented.

In his state-of-the-nation address last January, Morales identified the failure to resolve the TIPNIS conflict as a major shortcoming of his administration. “We didn’t achieve consensus on the road…in the end, we didn’t understand the reality of their [inhabitants of the TIPNIS] living situation,” he acknowledged. “We made a mistake.”

In retrospect, it’s apparent that the Morales government never abandoned its commitment to build the TIPNIS road. In October 2012, Morales signed a new construction contract for the 28-mile road segment leading to the park’s southern border (one of three sections comprising the original OAS contract, which he had cancelled the previous April to enhance the credibility of the forthcoming “consulta previa”). As of December 2013, construction on this first segment, which is being undertaken jointly by a state company and three cocalero union federations, was 30% complete. Financing is being provided entirely by the Bolivian government, replacing Brazil’s loan (for all three segments), which was withdrawn when the OAS contract was revoked.

Current status of the 3 road segments (Página Siete; used with permission).In recent weeks, public statements by Morales have anticipated the latest policy shift. In his Independence Day speech on August 6, Morales lamented the loss of Brazil’s guaranteed financing for the highway, due to “problems with the TIPNIS segment.” “We have lost time and resources,” he acknowledged, “but…we’re far advanced.” Later in the month, announcing plans for an industrial park in the Amazonian Beni department, he expressed regret that “due to [the opposition of] a small group of Bolivians, financing for the TIPNIS highway was lost,” depriving the region of its full commercial, touristic, and economic potential.

Current status of the 3 road segments (Página Siete; used with permission).In recent weeks, public statements by Morales have anticipated the latest policy shift. In his Independence Day speech on August 6, Morales lamented the loss of Brazil’s guaranteed financing for the highway, due to “problems with the TIPNIS segment.” “We have lost time and resources,” he acknowledged, “but…we’re far advanced.” Later in the month, announcing plans for an industrial park in the Amazonian Beni department, he expressed regret that “due to [the opposition of] a small group of Bolivians, financing for the TIPNIS highway was lost,” depriving the region of its full commercial, touristic, and economic potential.

On August 15, Minister of the Presidency Juan Ramón Quintana announced that more than $8.5 million has been invested in TIPNIS anti-poverty initiatives in fulfillment of Morales’s presidential mandate, including educational, productive, infrastructure, and telecommunications projects and delivery of basic services. Early in 2015, Quintana stated, the government will ask the UN, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), or another multilateral body to verify that extreme poverty in the TIPNIS has been eliminated.

Exactly why Morales has chosen this political moment to refocus attention on the TIPNIS road and conflict, rather than wait until after the election, is unclear. With his commanding lead in the polls (recently estimated at 59%), and the probability that the MAS will retain two-thirds control of the national congress, Morales may perceive a strategic benefit, and little cost, in shoring up the pro-development constituency that the TIPNIS conflict helped to consolidate.

At the same time, the multiple opposition parties to the left and right of the MAS are staking out alternative positions, in the hopes of capitalizing on the once-considerable opposition to the road—and to the government’s mishandling of the conflict—by urban middle class voters and some popular sectors. Candidates for the conservative PDC (Christian Democrat) and UD (Democratic Unity) parties are advocating for an alternative route outside the TIPNIS and/or an expanded water transportation network. The center-right MSM (Movement Without Fear) party opposes any road through the TIPNIS.

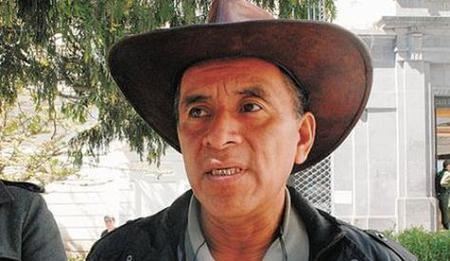

One candidate who stands to benefit from the revival of the TIPNIS issue is Fernando Vargas, an indigenous leader of the TIPNIS resistance who is running for president on the PVB (Green Party of Bolivia) ticket. Vargas has recently supported a proposal for a railroad that would connect the Cochabamba tropics with the Beni along a route east of the park. He views Morales’s anti-poverty initiatives in the TIPNIS as a double-edged sword, providing concrete benefits to communities while reinforcing their dependency on the proposed highway, which he perceives as the government’s ultimate objective.

Fernando Vargas (La Razón; used with permission).The PVB, a recently formed ecological party that is polling around 2% nationally, sees its current goal as popular education around the need for an alternative sustainable development model, through the election of congressional representatives. Two prominent MAS dissidents—Alejandro Almaraz, former Vice-Minister of Lands in first Morales administration, and Filemón Escóbar, ex-leader of the revolutionary mineworkers federation, founder of the MAS party, and mentor to Morales—are running on the PVB ticket for Senate and Congress, respectively.

Fernando Vargas (La Razón; used with permission).The PVB, a recently formed ecological party that is polling around 2% nationally, sees its current goal as popular education around the need for an alternative sustainable development model, through the election of congressional representatives. Two prominent MAS dissidents—Alejandro Almaraz, former Vice-Minister of Lands in first Morales administration, and Filemón Escóbar, ex-leader of the revolutionary mineworkers federation, founder of the MAS party, and mentor to Morales—are running on the PVB ticket for Senate and Congress, respectively.

Still, divisions and alliances around the TIPNIS conflict continue to evolve in unpredictable ways. Justa Cabrera, another indigenous leader of the first TIPNIS march, has recently rejoined the MAS party to campaign for Morales. She describes her shifting allegiance not as an alliance, but as a return to the organization she helped to found, in response to the mandate of the Guaraní people. “If the indigenous who inhabit the TIPNIS say they need a road,” says Cabrera, “I’m not going to be the one to say, don’t build this route.”

On a related front, opponents of the TIPNIS highway are keeping a close eye on Brazil’s October election, where upstart candidate Marina Silva appears to have a chance of winning the presidency on a second-round vote. Silva, an environmental activist and former Environmental Minister in the cabinet of Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, reportedly supported the first TIPNIS march and could be a leading force for sustainable economic development, and alternatives to extractivism, throughout the region.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner and the author of NACLA’s Rebel Currents blog, covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments (nacla.org/blog/rebel-currents).