Ed: The political consequences of the 1985 earthquake that devastated Mexico City were enormous. Not only did the scale of death and destruction, the haphazard rescue of survivors, and the government’s inability to map a coherent plan of reconstruction expose the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) as being both corrupt and incompetent, but the civic response to the corruption and incompetence gave rise to a new way of doing radical politics. This response is most often attributed to the emergence of a network of community reconstruction groups. Though the vertical organizing of the old radical model has not vanished, an increasing number of people are abandoning it. This new way is very much still with us.

It occurred in a slow, smooth, and mysterious manner. People stopped believing in one way of doing politics and instead began believing in another. This new way combined innumerable political innovations with the recovery of ancient forms of being, thinking, and living that had always constituted the core of Mexican social reality. Ordinary men and women, insubordinate, rebellious, dreamers, decided to retake control of their lives in an hour of horror.

If one had to put a date on something that has none, it would be September 19, 1985. As many have noted, the earthquake that destroyed the center of Mexico City quickly became a catalyst of collective action and made widely visible the forms of organizing that are now called horizontalism and autonomy.

It took some time for people to congregate at the rubble the morning of September 19. Those who were not directly trapped by the damage were the first to meet. Suddenly, leaving the watertight compartments of daily oppression, those who had been unaware of each other began a process of mutual re-cognition. They felt themselves to be co-citizens and made the city theirs again; the city that had been escaping from their grasp and was already only a common space for oppression and confrontation.

In the devastated zone there were some, closely affiliated with the PRI, who wished for the return of the hierarchical status quo. Others, however, opened themselves to personal communion and encountered one another. Their attitude was one of improvisation, their style one of informality, and their method one of convivial autonomy and masterful knowledge of concrete reality. Perhaps it took time to feel the urgency to recover a hope that had been lost after so many years of corruption and authoritarianism, to tear up the institutionalization of daily life, characteristic of modern societies, where recognition and dependence are depersonalized.

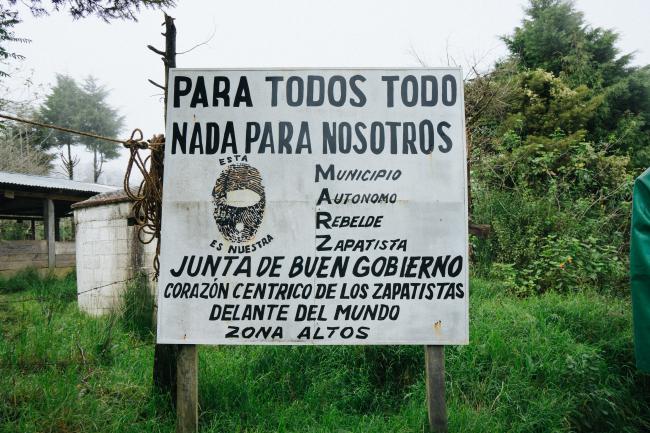

Ed: Nine years later, on New Years Day 1994, the day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect, an indigenous group calling itself the Zapatista Army of National Liberation rose up in the southern state of Chiapas to seize wide swaths of land and demand autonomy from the corrupt and authoritarian Mexican government. For more information on the state of Zapatismo today, see www.nacla.org/deathandresurrection. For more information on the Zapatista pedagogical center, the Escuelita, with accompanying photo essay, see www.nacla.org/escuelita.

The Zapatista movement has some of its roots in this explosion of collective action. In the period leading up to the uprising, Subcomandante Marcos, with a small group of professional revolutionaries, had been in the Lacandon Jungle learning with the indigenous communities how to build Zapatismo. After the uprising, many thousands took to the streets to say rapidly and effectively that the Zapatistas were not alone, but that they did not want more violence. The Zapatistas obeyed: from January 12, 1994 onward they did not fire a single shot, not even in self-defense against the constant paramilitary attacks. However, they were bewildered. As Marcos said, somewhat perplexed, they had prepared for war, not for the dialogue that civil society imposed on them. They learned quickly to focus on dialogue and became deeply dedicated to it, but they had to change their interlocutor. When the government and political parties betrayed their word and signature on the San Andrés Accords—a peace agreement signed in 1996 that granted recognition and autonomy to indigenous communities in Mexico—the Zapatistas concentrated their efforts on civil society.

With the Zapatistas, as with the post-earthquake neighborhood movements of Mexico City, the departure from the Leninist doctrine that presided over the twentieth century has not stemmed from a theoretical debate. Instead, it has been the expression of a practice that has employed new words or has given a new meaning to words already in use. For example, in Mexico, the term “civil society” itself gained a new meaning and value in the 1980s. The mobilization and initiatives associated with the 1985 earthquake redefined it as a community effort in self-management and solidarity—a space independent of the government, but a zone of antagonism. While the expression “horizontalism” is rarely used by civil society actors in Mexico, throughout the pueblos and barrios, community members have been rejecting vertical forms of organization, opting instead for a horizontal framework.

The Zapatistas also brought autonomy—a word with a long tradition in Mexican popular movements—to the center of political debate, joining it with “civil society” and giving it new energy and meaning. But not just any kind of autonomy. The Zapatistas quickly discarded the school of thought, similar to the European autonomous tradition adopted in Nicaragua, that saw autonomy as part of a process of political decentralization, fully subsumed to state order.

The notion embodied in the San Andrés Accords, with which the government did not comply, included three elements: ontonomy, autonomy, and heteronomy. Ontonomy is the regulation based on one’s own cultural tradition; autonomy, regulation appropriate for the current generation, modifying tradition; and heteronomy, regulation imposed from outside, rejected by autonomous construction. In practice, autonomy covers not only aspects of regulation, but also those related to self-sufficiency and self-management.

In August and December of 2013 and January of 2014, the Zapatistas organized a course called “Freedom According to the Zapatistas,” in which some six thousand people participated. The courses were part of a social justice school the Zapatistas named the Escuelita, or “little school.” Ordinary men and women, the same ones who were constructing a new society, taught the courses in the Zapatista communities directly, drawing in a global network of activists to participate.

The “students” were able to see firsthand how Zapatista norms that regulate daily life were developed in the communities, the municipalities (groups of communities), and the zones (groups of municipalities). The governing framework of decisions and power relations was established from the bottom up, shared universally, instead of proceeding from an elite downwards.

Most emblematic of Zapatista norms is the notion of “mandar obedeciendo” or “rule by obeying.” The seven principles of “rule by obeying” are applied to those in positions of authority: serve others and not yourself; represent others and don’t supplant them; construct and don’t destroy; obey and don’t command; propose and don’t impose; convince and don’t conquer; work from below and don’t seek to rise. The revolutionary laws were written clandestinely before the uprising and then published on January 1, 1994. Many people were involved in their development, and in step with Zapatista horizontalism more generally, their language is not attributed to any specific individual, and is open to continual revision.

Within Zapatista territory, there are no police—and they are not needed. Despite the continued experience of external aggression by the state, the Zapatista territory is one of the safest in Mexico. Domestic violence has been reduced, which is particularly significant in pueblos where hitting women and children had been generally accepted. In place of a policing body, everyone participates in various types of commissions to watch over and control government functions as well as the implementation of the communal projects. This helps assure transparency and accountability.

Since an army cannot operate neither democratically nor horizontally—commanders give orders and the troops obey—when the Zapatistas emerged as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, bent on seizing and holding national territory, its community base of support, men and women, concentrated their power in the hands of political-military men to organize the uprising.

The leaders of social movements and revolutions typically hold onto the power that brought them to triumph and expand it when facing new situations. It has not been like that among the Zapatistas. The power that they had originally concentrated within the leaders has now been gradually returned to those who granted it, restoring the Zapatista notion of “power from below.”

Along the way, during the difficult dialogue with the government, the Zapatistas constructed a speaker in Subcomandante Marcos. Once he had played his role, they destroyed their creation. In his goodbye speech on May 24, 2014, he recalled some Zapatista milestones:

His demands: “Against death, we demand life. Against silence, we demand words and respect. Against forgetting, memory. Against humiliation and contempt, dignity. Against oppression, rebellion. Against slavery, freedom. Against imposition, democracy. Against crime, justice.”

His practices: “From revolutionary vanguardism to ‘rule by obeying’; from taking power from above to the creation of power from below; from professional politics to everyday politics; from the leaders to the pueblos; from gender marginalization to the direct participation of women; from mocking otherness to the celebration of difference.”

“It is our conviction and our practice,” say the Zapatistas in summary, “that to rebel and to fight it is not necessary to have leaders nor caudillos nor messiahs nor saviors. To fight it is only necessary to have a little bit of humility, some dignity, and a lot of organization.”

Gustavo Esteva is a grassroots activist and public intellectual, former advisor to the Zapatistas, and founder of the Universidad de la Tierra. He writes columns for La Jornada and occasionally for The Guardian. Translated by Naomi Glassman.

Read the rest of NACLA’s 2014 Fall Issue: Horizontalism & Autonomy