For our web edition, NACLA partnered with digital news site Mas de 131 to translate original coverage of the supposed “resignation” of Zapatista Sucommander Marcos last May. See original article here.

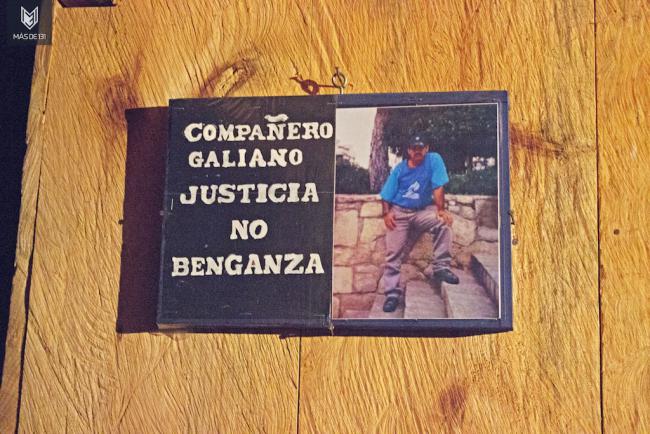

La Realidad, Chiapas, May 24, 2014. At the premises of the Caracol I: La Realidad the crowds are gathering. Support bases of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) are grouped into two blocks facing one another on a basketball court in honor of the Zapatista José Luis Galeano López Solís, who had been killed by paramilitaries.

Commander Tacho, member of the General Command of the EZLN, guides the Zapatistas as they arrange into their formation. Then the militiamen move to the front of the support bases, forming a line.

They all wear a patch over the right eye while keeping their left eye fixed on the crowd gathered at the auditorium. On command, they move into a close formation with arms linked. They look down and to the right, then down and to the left, and center. Finally, they look up into the sky and advance, marching.

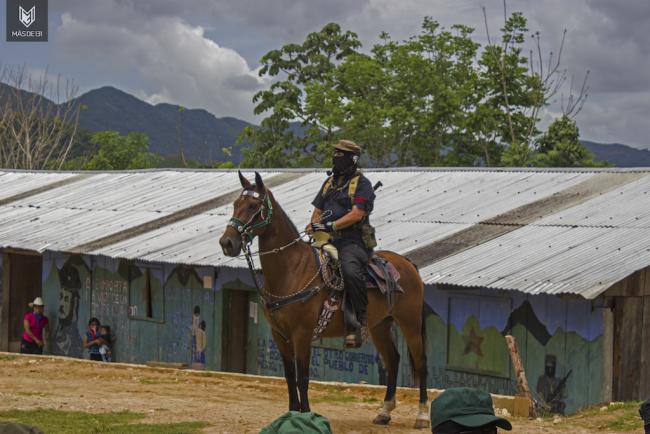

Sub Marcos enters on horseback, also wearing a patch over the right eye. He carries a machete on his back. The song “Latinoamérica” by Calle 13 queues his entrance. Out comes the rest of the EZLN leadership. They greet Marcos, the attendees, and the civilian support bases. Like several people in the crowd, they each have on a black ribbon. At the end, they fall back in line.

Sub Marcos enters on horseback, also wearing a patch over the right eye. He carries a machete on his back. The song “Latinoamérica” by Calle 13 queues his entrance. Out comes the rest of the EZLN leadership. They greet Marcos, the attendees, and the civilian support bases. Like several people in the crowd, they each have on a black ribbon. At the end, they fall back in line.

“You are not alone!” they yell. “Galeano lives!”

The transmission of the Zapatista radio station Radio Insurgente begins. Marcos’s voice comes on to introduce Subcommander Moisés, who will present the results of the investigation that the EZLN command is conducting in relation to the murder of Galeano. “We are not like them, our anger is directed against the system,” says Moisés, referring to the members of the self-described “historic” Independent Central of Agricultural Workers and Peasants (CIOAC), who were responsible for the murder of Galeano. He denounces the divisions that within CIOAC lead to internal threats and bribery. Citing the Fray Bartolomé de las Casas Human Rights Center as a witness, he stresses that CIOAC never approached the Zapatista support bases to start a conversation.

“They are killing each other,” accuses Moisés, who also announced that it was a woman who struck Galeano in the mouth with a machete, and another woman who dragged the body of the murdered Zapatista.

At the end of his speech, one thing is clear: Galeano is and will continue to be the unforgettable companion.

A new speaker takes the stage. Fortunately for the more than one thousand people present—sent from the five Zapatista administrative centers, or caracoles, from national and international civil society, and from the “Caravan of Justice for the Compa Galeano!”—the sun subsides.

Facing the crowd, two men carry a crown of flowers to commemorate Galeano, and to their sides, two women hold white bouquets.

Dressed like the rest of the militia, Subcommander Moisés takes a roll of paper out of his clothing, and with a dynamic voice, starts reading. He explains the presence of the army in the caracol: “The EZLN cannot barge into autonomous communities or governments as it pleases,” he says. “It can only intervene in community business when requested to do so, because the military must serve the civilians.”

He highlights the importance of the Zapatista dictum “rule by obeying.” The EZLN was present at this mostly civilian event because the Good Government Council of La Realidad had asked for its presence and support.

According to his statement, counterinsurgency has worsened in the region. Social programs are used to feed paramilitary groups: in exchange for instigating and attacking Zapatista communities, members of these groups benefit from the social welfare program “Oportunidades” and other institutional projects, whether state or federal.

Moisés directly accuses Florinda Sántiz, councilor for the National Action Party (PAN) in Las Margaritas. According to the insurgent, Sántiz—in conjunction with Governor Manuel Velasco, former governors, the commissioner for peace, Luis H. Alvarez, and several senators and deputies—has orchestrated CIOAC’s paramilitary work, which culminated in the assassination of “compa” Galeano.

This form of doing politics is not isolated, but is in fact part of the counterinsurgency tactics mandated by the federal government. They, continues Moisés, say they will do the same in other caracoles. He then describes a series of attacks that the CIOAC has carried out in different autonomous Zapatista municipalities.

“We had to choose our people and so we did,” says Moisés. “We came to La Realidad, where there’s pain and anger. They are our food and our destiny. They are us. “

Night draws near. A light drizzle, reluctant to become rain, teases us for brief moments, while the crowd grows impatient waiting for a press conference.

Subcommander Tacho comes and goes. He gives orders through the microphone, points to empty seats, and tells independent media representatives to take their places in front of the platform. At midnight the press conference begins.

With his face covered by a pirate’s eye-patch, Marcos reads the communiqué “Between Light and Shadow,” in which he announces his own death. Or at least the death of that colorful ruse he had had to don.

He recounts the last twenty years of the EZLN. He speaks of generational rebirth, in light of the fact that the insurgents and voters of the Zapatista’s pedagogical experiment in autonomous organizing, the escuelita, or little school, were mostly young people. He then talks of other kinds of rebirth, such as that of ideological rebirth. Marcos uses the example of the paradigm shift from vanguardist Marxism to that of “rule by obeying,” part of the Zapatista Good Government principles.

“An army may strive to find peace where it has disappeared,” Marcos says. He explains that the EZLN is an army that prefers to “cultivate life rather than worship death.” However, he said that the EZLN still maintains a military and insurgent consciousness. He then remembers the attention that the media has paid him.

“Marcos was a colorful ruse,” he says ironically. But he then points out: “He was Non-Free Media—which is not the same as being paid media.” He then recounts how he was publicly presented by the government of Ernesto Zedillo as: Guillén, university student originally of Tamaulipas.

He talks of the sixth Declaration of the Lacandonian Jungle and the efforts that followed it, such as the festival of Righteous Rage, the Other Campaign, and more recently, the course on freedom according to the Zapatistas, where people came to dialogue.

“Now masks are no longer necessary,” he says.

“These will be my last public words until I cease to exist. It has been a collective decision,” asserts the Subcommander. Then he explains that his stepping down is not because of disease or death.

Subsequently, Marcos recounts the story of those killed during the police repression in San Salvador Atenco in 2006, the murders of Ostula, Bachajón, Guerrero, Oaxaca, and Juan Francisco Kuykendall.

He speaks of justice, a “small” justice. He speaks of pain and of listening closely to the decision that the EZLN should make.

We think that it is necessary for one of us to die so that Galeano lives.

To satisfy the impertinence that is death, in place of Galeano we put another name, so that Galeano lives and death takes not a life but just a name—a few letters empty of any meaning, without their own history or life.

He announces the end of the story of Don Durito from the Lacandonian Jungle, and of old Antonio: “The children will not cry because they are all grown up and able to judge for themselves.”

And then there’s silence. Marcos has left, it is Insurgent Subcommander Galeano that speaks now. Moisés, now military leader and official spokesperson of the EZLN, announces the end of the press conference: “You may go and sleep or dream, as you please.”

This coverage was a collective effort among different media platforms frequently considered free, alternative, independent, or whatever.

Read the rest of NACLA’s 2014 Fall Issue: Horizontalism & Autonomy