On August 13, President Evo Morales promulgated a new law ending the special “untouchable” status of the Isiboro-Sécure Indigenous Territory and National Park (TIPNIS) in the Bolivian Amazon, and allowing construction of a controversial highway through the reserve.

Almost six years earlier to the day (on August 15, 2011), some 1,000 indigenous TIPNIS residents and their supporters began a 360-mile trek from the Amazon lowlands to La Paz to protest Morales’s inauguration of the proposed 182-mile road, whose central segment would bisect the 4,630 square mile reserve. The TIPNIS, doubly “protected” as an indigenous territory and a national park since 1990, is the ancestral homeland of the Chimáne, Yuracaré, and Moxeño- Trinitario peoples, who collectively own most of its land. Some 8,000–12,500 native indigenous subsist on fishing, hunting, and foraging activities throughout the park, which is among the most biodiverse regions in the world.

In a spectacle that shocked the nation, the march was brutally repressed by police at Chaparina, leaving at least 70 wounded. In the wake of the tragedy, Morales agreed to cancel the road. In October 2011, he signed a law banning its construction and protecting the reserve as an “untouchable” zone. This effectively put the road on hold—even after a bitterly-contested government-sponsored consulta concluded that 80% of the TIPNIS communities polled supported it.

The TIPNIS conflict, which pitted pro-road campesino and cocalero (coca grower) sectors against dissident lowland indigenous groups, is widely viewed as a turning point in Bolivia’s “process of change.” It profoundly altered the country’s political and social landscape by rupturing the Unity Pact, the insurgent alliance of social movements that brought Morales to power in 2005. It exposed the contradictions of Morales’s global championship of indigenous and environmental rights while promoting destructive projects at home. It also sparked a new grassroots resistance to the extractivist development model which has increasingly challenged Morales and the ruling MAS (Movement Towards Socialism) party.

To outside observers, Morales’s seeming policy reversal and revival of this long-dormant controversy may seem perplexing, especially coming at a time when his popularity has waned and his political future is uncertain. In February 2016, Morales narrowly lost a referendum bid that would have allowed him to run for a fourth presidential term in 2019, leaving his supporters to pursue a variety of complex legal strategies to permit his candidacy. So, as the daily Página Siete recently pondered, does the new TIPNIS law signal political suicide for Morales, or is it a bold strategy to aid his re-election?

Evolution of Government Policy

Morales insists that the new move to legally “de-protect” the TIPNIS is not necessarily a decision to build the road. Still, the law explicitly authorizes roads and highways through the TIPNIS, and allows private exploitation of the reserve’s natural resources “in association with” indigenous TIPNIS groups. Morales himself affirmed in July that “sooner or later, this road will be built.”

In retrospect it’s apparent that the Morales government has never abandoned its commitment to the road, but has continuously tailored its official narrative to political expediency. In April 2013, in the run-up to the 2014 presidential election, Morales announced that the road would be “on hold” until extreme poverty in the TIPNIS was eliminated, with an estimated three-year timeframe.

Subsequently, both Morales and Vice-President Alvaro Garcia Linera acknowledged misgivings about the political viability (but not the geopolitical merits) of the road, and the government’s much-contested consulta process. “We didn’t achieve consensus on the road…in the end, we didn’t understand the reality of their [inhabitants of the TIPNIS] living situation,” Morales lamented in his 2014 state of the union address. “We made a mistake.”

After Morales’s resounding (61%) victory in October 2014, which consolidated the MAS as a national power with two-thirds control of both legislative branches, plans for the TIPNIS road resurfaced. They intensified in 2015 when MAS won the governorship of Beni, the Amazonian department where half of the TIPNIS road is located—after the electoral commission had decertified the entire slate of the rival opposition party. (In 2011, the opposition Beni governor supported the indigenous protestors and opposed the road.)

As a final measure, within the past few years Morales has initiated construction on the two highway segments that connect with the TIPNIS road at the park’s northern and southern borders. (All three sections were originally combined in a single contract with the Brazilian firm OAS, which Morales revoked in April 2012.) The southern segment, now complete, was built by a joint venture between the state and a construction cooperative sponsored by the cocalero union federation, with government financing. The northern section is being undertaken directly by the Binational Army Corp of Engineers (Bolivia-Venezuela).

Arguments For and Against the Road

The new law has already sparked bitter controversy, reviving old arguments for and against the road, with some new twists.

According to Morales, the primary beneficiaries of the law will be the indigenous communities of the TIPNIS, whose desperate needs for basic services and infrastructure cannot be addressed while the reserve remains “untouchable.” The impetus to end “untouchability” and revive the road, he emphasizes, comes directly from indigenous organizations within the TIPNIS, which sponsored the legislative proposal. The government, he says, is merely following the mandate of the 2012 consulta.

By linking the departments of Beni and Cochabamba, the road will also integrate the country’s Amazonian and Andean regions, a dream since Bolivian independence. As the new MAS governor of Beni has emphasized, the “liberation” of Beni—long eclipsed by its eastern rival, Santa Cruz—from historical isolation will provide a much-needed boost for the department’s agricultural and meat-producing economy.

Finally, the government reasons, since the two connecting sections of the road are under construction, the TIPNIS road is a fait accompli. All that remains is to consolidate the central section, which has already been significantly breached by illegal logging activity.

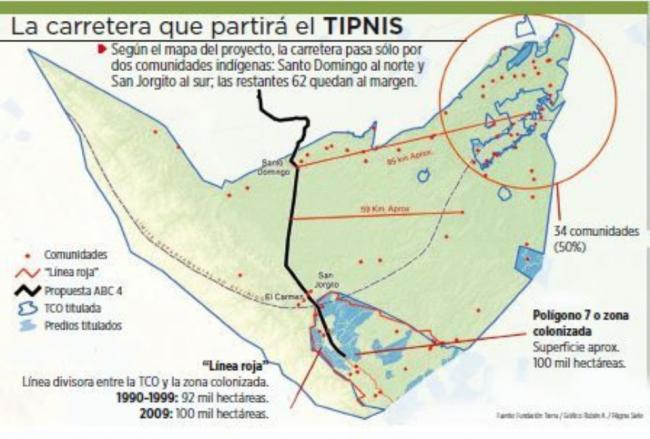

Opponents of the road—including indigenous TIPNIS leaders, environmental activists, and allied civil society organizations—counter that only a handful of TIPNIS communities are located close enough to the historically-proposed north-south route to benefit from enhanced access to services. Most are remote river villages, located “two days by water or three days by trek” from the road. Even so, critics contend, the government is constitutionally mandated to provide basic services to all TIPNIS residents, regardless of where they live or of the reserve’s “untouchable” status.

In fact, critics note that during the run-up to the 2014 presidential election, Morales committed more than $8.5 million to TIPNIS communities for education, health, infrastructure, and telecommunications projects. The government has acknowledged commencing construction on 3 bridges in or bordering the protected zone, well before its “untouchable” status was lifted.

As to the popular mandate established by the government consulta, an independent commission sponsored by the Catholic Church and human rights organizations concluded that the process was deeply flawed, and inconsistent with the requirement to secure “free, prior, and informed consent” established by Bolivian and international norms. Of the 35 communities surveyed by the Commission, 30 stated that they rejected the road. Among other things, the Commission found that the government manipulated and divided indigenous communities with offers of conditional benefits (such as outboard motors), biasing the results of the process and splitting groups into pro- and anti-road factions or parallel organizations.

What opponents fear most is that the highway will open up the TIPNIS to deforestation, environmental degradation, and colonization, principally by coca farmers pushing up from the park’s southern border. This taps into a long-standing conflict between lowland indigenous groups native to the TIPNIS and highland indigenous (Aymará and Quechua) migrant settlers who have colonized southeastern Bolivia, including portions of the TIPNIS, over the past 50 years, primarily as coca farmers.

The cocalero union federations of the Cochabamba tropics (organized and headed to this day by Evo Morales, and headquartered in Villa Tunari, gateway to the TIPNIS from the south) are a critical bastion of MAS support. They recently won passage of a law that increases the allowable coca-growing acreage. TIPNIS leader Fernando Vargas, who headed the 2011-12 protest march, has raised the specter of “35,000 cocaleros just waiting for the [TIPNIS] highway to be built.” Morales, however, insists that no expansion of coca cultivation will be permitted in the national parks.

Still, the Morales government is now openly encouraging hydrocarbons exploration in protected areas, raising growing concern about the 3 concessions already held by transnational oil companies in the TIPNIS. Taken together, these risks are perceived as posing a substantial threat to the livelihoods, culture, and the very survival of indigenous peoples in the TIPNIS, and to the sustainability of the region’s already fragile ecological balance and environment.

For Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linera, this critique reflects an “environmental colonialist” mentality, which U.S.-linked NGOs seek to impose on indigenous communities to impede their development and Bolivia’s national sovereignty. Any road built through the TIPNIS, he insists, will be an “ecological highway,” required by the new law to be designed with indigenous participation and in compliance with environmental norms. Critics say there is no sustainable solution along the historically proposed route that would bisect the reserve. To date, the government has been unwilling to consider alternative routes outside the park.

Resistance and Its Limits

Indigenous road resisters and their allies have mobilized quickly in response to the new law, holding a vigil outside the official promulgation event (where they were barred from entry) and supportive protest rallies, sit-ins, and marches in the major urban centers. Government officials have been repeatedly harassed at speaking events, gathering continuous media attention.

Among the strategies being pursued are legal actions to challenge the “de-protection” law (by popular initiative and/or a recourse of unconstitutionality), a national referendum on the highway sponsored by an ad hoc citizens group, and a possible new march to La Paz, to be determined later this month. “If the government wants a confrontation,” says Vargas, “we’re ready.”

The resistance has been buoyed by the emergence of a new generation of youthful TIPNIS leaders, including children of the 2011 marchers. Traditional allies such as the Catholic Church, environmental NGOs, and human rights organizations have continued to play a strong supportive role. TIPNIS organizations are also increasingly linking their struggle with those of indigenous groups resisting other megaprojects, such as the Chepete-El Bala dam, to advance a common critique of Morales’s extractivist development model.

New potential allies include the COB (Bolivian Workers Central, the national trade union federation) which has declared its opposition to the “de-protection” law—although its position on the TIPNIS road in the past has been inconsistent, reflecting its shifting relationship with Morales. Support from opposition politicians newly converted to the TIPNIS cause, which TIPNIS leaders are seeking to manage strategically, is of more dubious value.

Other former allies are conspicuous by their absence. Bolivia’s current human rights Ombudsman, David Tezanos, who is appointed by the MAS-controlled legislature, has openly endorsed the “de-protection” law as consistent with the mandate of the consulta (unlike Rodolfo Villena, the former Ombudsman, who played—and has continued to play—a key role in supporting the TIPNIS resistance). UN representatives in Bolivia have affirmed that “untouchability” is not a right of indigenous peoples.

Morales has actively sought to silence prominent critics of the road like Pablo Solón, his former UN ambassador (and subsequently Bolivia’s chief international climate change negotiator), who resigned over the first TIPNIS conflict. Solón is currently defending against criminal charges that are widely viewed as retribution for his outspoken criticism of the government’s extractivist development policies.

Still, the most significant limitation faced by the resistance is an internal one: the growing sense among lowland indigenous communities that, after years of coercion and conflict, “cutting a deal” to access resources and benefits is preferable to struggling against the powerful prevailing political and economic tides. The growing number of indigenous communities in the southern portion of the TIPNIS that have become linked to the economies of their cocalero neighbors, and that stand to benefit from the road, is another complicating factor.

A Political Strategy?

In seeking to revive the TIPNIS road, Morales is appealing to a broad range of constituencies that will benefit directly from its construction. These include Cochabamba farmers and coca-growers seeking improved market access for their products, the burgeoning commercial, transportation, and construction sectors based in Villa Tunari, agricultural and meat producers in Beni, and an emerging business class in its capital city of Trinidad. Both departmental capitals have received significant investment from the Morales government, and the TIPNIS road is expected to radically expand the economic and political influence of these satellite population centers.

These groups are representative of the new urban-rural popular-business bloc or “indigenous bourgeoisie,” a critical element of the pro-growth, pro-development coalition consolidated by Morales after the 2011 TIPNIS crisis, as the new social-political base of the MAS. Anchored by this new coalition, which propelled the MAS to a decisive victory in 2014, Morales has launched an ambitious 5-year public investment program in transportation, energy, and related infrastructure sectors.

This National Development Plan will advance Bolivia’s agricultural, mining, and hydrocarbons frontiers while providing growth opportunities for the new entrepreneurial constituencies that Morales’s successful economic policies have nourished. China has emerged as a readily-available financing source (and contractor) for these projects, under a $10 billion line of credit arrangement.

The TIPNIS road fits squarely within these parameters. By championing it again now—and demonstrating his continuing ability to prevail over controversy—Morales is likely betting that he can shore up key elements of the MAS political-social base to support his 2019 candidacy against possible internal rivals, and deliver their tacit acceptance for whatever legal maneuvers may be necessary to accomplish this (such as an arrangement for his temporary resignation). Especially as the looming economic downturn raises anxieties—and the potential for political volatility—among these newly-properous constituencies, Morales is demonstrating that he intends to protect their interests and needs.

Of course, this strategy could be derailed by any number of variables. While Morales’s approval ratings continue to hold at close to 50%, even after passage of the “de-protection” law, last year’s bitterly contested referendum revealed a level of unpredictability in the Bolivian electorate that few imagined.

One possible wild card has been introduced by ex-President Carlos Mesa, who recently entered the political fray to accuse Morales of “mortgaging Bolivia’s water and air” by “de-protecting” the TIPNIS. Mesa, a centrist neoliberal who currently represents Bolivia before the International Court in Bolivia’s efforts to regain its seacoast from Chile, could be a formidable rival to Morales if he chooses to run against him.

For indigenous road resisters, environmental activists, and their allies, the need and opportunity for a broad-based popular coalition to challenge and present viable alternatives to the prevailing extractivist and megaworks-focused development model has never been greater.

Emily Achtenberg is an urban planner, a member of NACLA’s Editorial Board, and the author of NACLA’s Rebel Currents blog covering Latin American social movements and progressive governments.