It used to be generally frowned upon to openly call for military coups and U.S. intervention in Latin America. Not anymore. At least not when it comes to Venezuela, a country whereaccording to the prevailing narrativea brutal dictator is starving the population and quashing all opposition.

Last August, President Trump casually mentioned a “military option” for Venezuela from his golf course in New Jersey, provoking an uproar in Latin America but barely a peep in Washington. Similarly, Rex Tillerson, then-Secretary of State, spoke favorably about a possible military ouster of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro.

In recent months, opinion pieces suggesting that a coup or a foreign military intervention in Venezuela might be a good thing have dotted the U.S. media landscape: from the Washington Post to Project Syndicate to The New York Times. Occasionally a pundit argues that a coup d’état could have undesirable consequences, for instance if a hypothetical coup regime should decide to deepen relations with Russia or China.

Rarely does anyone point out that this is an insane debate to be having in the first place, particularly regarding a country where elections occur frequently and are, with few exceptions, considered to be competitive and transparent. On Sunday, May 20th, Maduro will be up for reelection. Polls suggest that, if turnout is high, he could be voted out of office.

The fact that coups, not elections, are the hot topic is a sad reflection of the warped direction that the mainstream discussion on Venezuela has taken. For many years now, much of the analysis and reporting on the oil-rich but economically-floundering nation have offered a black-and-white, sensationalized depiction of a complex and nuanced internal situation. In addition, there has been little serious discussion of the Trump administration’s policies toward Venezuela even as they wreak further damage to the country’s economy, worsen shortages of life-saving medicines and food, and undermine peace and democracy.

Hardening Sides

Lest we forget, Madurooften described by U.S. politicians and pundits as a dictatorwas democratically elected in snap elections carried out a month after the death of his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, in early 2013. As a presidential term lasts six years in Venezuela, his current constitutional mandate will end in early 2019.

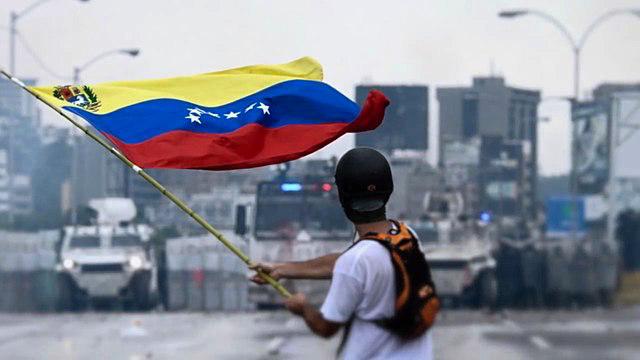

From the get-go, some sectors of the Venezuelan opposition rejected Maduro’s legitimacy and called for his immediate departure from office. In 2014 and again in 2017, they endorsed protest movements explicitly aimed at generating major disruptions in key urban areas to try to force the removal of the government, for example through overwhelming popular pressure or via internal or external military intervention.

Though many of these protests were peaceful, others became violent and resulted in dozens of fatalities, some attributable to state security forces and others attributable to members of the protest movement, according to credible reports and documentary evidence. Hundreds of protesters were detained, and a few opposition figures, including former Chacao mayor Leopoldo López, were sentenced to jail for allegedly inciting violence. López is currently under house arrest after serving three years in prison.

Opposition supporters believe that the due process rights of López and others involved with the protests were violated, and there certainly are grounds for this argument. Meanwhile, some government supporters believe that these individuals deserved harsher penalties for having attempted to usurp the popular will through destabilization and violence, in a manner reminiscent of the lead-up to the short-lived 2002 military coup against Chávez that López and other opposition leaders were involved in.

In late 2015, Venezuela’s opposition won a large majority of seats in National Assembly elections. But the country’s executive and legislative branches were soon at loggerheads over alleged cases of electoral fraud that led Venezuela’s Supreme Court, a body that is widely seen as loyal to the government, to disqualify three opposition legislators. The removal of these legislators meant the loss of the opposition alliance’s two-thirds supermajority that gave it broad powers to intervene at the executive level.

The opposition cried foul and refused to abide by the court decision. In response, the court refused to recognize the legitimacy of the parliament. Venezuela’s institutions ceased to interact according to the constitutional playbook and each side adopted increasingly radical tactics to try to gain the upper hand.

Opposition leaders supported a new series of protests that grew increasingly combative and violent, paralyzing key thoroughfares in Caracas and other cities for days at a time. Groups of protesters clashed frequently with security forces and dozens of people were killed, including protesters, state security agents, and bystanders.

The Maduro government responded to the growing chaos in the streets by convening elections for a National Constituent Assembly that would draft a new constitution and, according to Maduro, bring “order, justice, peace” to Venezuela.

The opposition, denouncing the initiative as a ploy designed to displace the National Assembly, boycotted the elections. Unsurprisingly, the new body is almost entirely pro-government and the U.S. and allied governments have refused to recognize it. Following the Constituent Assembly elections, the protest movement floundered and the opposition grew more divided, with hardliners calling for further boycotts of the subsequent regional and municipal elections. As a result of this and other factors, opposition voters failed to mobilize and the government won a majority of votes in both electoral contests in late 2017.

The Economy

The backdrop to Venezuela’s prolonged political crisis has of course been the country’s ever-worsening economic quagmire. Though plunging oil prices have certainly played a role, Maduro undoubtedly bears part of the responsibility for the deep depression and hyperinflation that has prompted hundreds of thousands of his countrymen to emigrate and caused his poll numbers to plummet.

While many ideologues blame “socialism” for the country’s economic ills, most economists point to a set of policy errors that have little or nothing to do with socialism. Most devastating has been the dysfunctional exchange rate system, which has led to a worsening “inflation-depreciation” spiral over the past four years, and now hyperinflation. Free gasoline and price controls that didn’t work also contributed to the crisis. The Trump administration’s financial sanctionsmore than all previous destabilization efforts, which were significanthave made it nearly impossible for the government to get out of the mess without outside help.

As if this profoundly distressing situation weren’t enough, media outlets have frequently published exaggerated accounts of the conditions in Venezuela, depicting widespread starvation, for instance. To be sure, soaring food prices have contributed to increased undernourishment throughout the country, but this is a far cry from a large scale famine.

More importantly, there has been scant U.S. media reporting on the further economic damage provoked by the Trump administration’s financial sanctions, announced in late August last year (shortly after Trump’s statement about a “military option” for Venezuela).

As my colleague Mark Weisbrot has explained, Trump’s unilateral and illegal financial embargo which cuts Venezuela off from most financial markets has had two major consequences, both of which entail increased economic hardship for the Venezuelan people. First, it causes even greater shortages of essential goods, including food and medicine. Second, it makes economic recovery nearly impossible, since the government cannot borrow or restructure its foreign debt, and in some cases even carry out normal import transactions, including for medicines.

Aside from fomenting greater economic havoc in Venezuela, Trump and his coterie of advisors on Venezuela, including Republican Senator Marco Rubio, have supported opposition hardliners in their efforts to scuttle attempts at dialogue and undermine elections, even when these offer the possibility of a peaceful political transition.

Case in point: this Sunday’s presidential elections. Opposition leader Henri Falcón a former governor and campaign manager of the opposition’s 2013 presidential candidate, Henrique Caprilesis running as an independent candidate against Maduro and three other candidates. Several major opposition parties are boycotting the election because, among other reasons, they object to the early date of the elections, which they say leaves them insufficient time to organize a strong campaignthe electoral authority did, however, agree to a one-month delay from the initial date. Two opposition parties, First Justice and Popular Will, were also unable to register candidates because they allegedly didn’t meet the formal requirements to do so.

However, voter surveys carried out by Datanalysis, Venezuela’s most frequently cited pollster, indicate that Falcón would win if there’s a high turnout. Before confirming his candidacy, Falcón secured strong guarantees from the country’s electoral authority, ensuring transparency, voter accessibility and vote secrecy, as in all contested prior elections since Chávez took office in 1999.

But the Trump administration, after unsuccessfully threatening Falcón with individual financial sanctions if he didn’t give up his candidacy, has supported the election boycott by more hardline opposition sectors that see Falcón, who was a Chávez ally until 2010, as too willing to compromise with chavistas if elected. The U.S. administration has even threatened sanctions targeting Venezuelan oil if the elections are held. Sources indicate that when both Falcón and the Venezuelan government requested that the UN send an international observation team to monitor the elections, U.S. officials intervened to ensure that no such monitoring effort would take place.

With the U.S. government and Venezuela’s opposition doing their best to empower hard-liners’ call for a boycott, there is a high probability that turnout from the opposition camp will be low and that Maduro will win the election by a strong margin. We can expect the administration to immediately denounce a “fraudulent” and “illegitimate” process and take further actions that will make life even more difficult for ordinary Venezuelans.

Regime Change in Venezuela: An Ongoing U.S. Policy

It’s worth noting that Trump’s Venezuela policy is mostly a continuation of President Obama’s policy toward Venezuela, although the financial embargo and calls for a military coup are particularly outrageous and disdainful of international law and the norms of civilized nations. The Trump sanctions build on an Obama sanctions regime identifying Venezuela as an “extraordinary threat to national security.” Around the time that Obama initiated a process of normalizing relations with Cuba, he began targeting assets of various senior officials and individuals associated with the Maduro government.

Under Obama, the U.S. government continued Bush-era funding to opposition political organizations in Venezuela and lobbied regional governments, again and again, to censure Venezuela in multilateral organizations, like the Organization of American States (OAS). It also refused to accept a Venezuelan ambassador to Washingtonwhile inviting one from Cubaand joined hard-liner opposition members in refusing to recognize Maduro’s electoral win in April 2013.

Essentially, the Obama administrationlike the Bush administration, which was involved in the short-lived 2002 coup against Hugo Chávezhad a policy of promoting “regime change” in Venezuela. That policy has taken a more aggressive, overt, and dangerous direction under Trump.

Sadly, there has been virtually no criticism of U.S. government efforts to topple the Venezuelan government anywhere in the major media. In the U.S. Congress, where a large number of legislators now oppose the embargo against Cuba, for instance, there is little outcry, with the important exception of a small group of progressive Democrats who have opposed sanctions against Venezuela, under both Obama and Trump. The majority of the political and media establishment appears to believe that Trump has the right policy agenda for Venezuela, with many liberals pointing to cases of corruption, human rights violations and other crimes allegedly involving Venezuelan officials as justification for harsh measures.

Yet none of these critics are calling for broad economic sanctions against Latin American countries with far more violent and repressive records. Against Honduras, for instance, where the military was recently deployed to violently repress peaceful demonstrations following fraudulent elections, which the U.S. government recognized. Or against Colombia and Mexico, where, over the last few months, dozens of political candidates and social leaders have been killed with impunity.

Venezuela is treated differently by the U.S., for obvious reasons: it has a government that seeks to be independent from Washington and it sits atop hundreds of billions of barrels of oil reserves, whichwhen the Venezuelan economy finally recovers will enable the government to have far-reaching regional influence.

In fact, that is exactly what happened during the Chávez administration. Venezuela grew in popularity in Central America and the Caribbean thanks in great part to the government’s generous Petrocaribe initiative, which brought tangible economic benefits to many countries in the region. It was also influential in building regional institutions such as the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) and the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), which were much more independent of the U.S. than the Organization of American States, located in Washington, DC.

Regardless of how one feels about Venezuela’s current government, it is time to acknowledge that U.S. policy towards that country is making things worse. It is generating greater economic pain, instability and political polarization in Venezuela and undermining the odds of reaching a peaceful solution to the country’s political crisis.

Talk of coups and military intervention in Venezuela, or anywhere in Latin America, needs to return to its previous taboo status, particularly given the current U.S. leadership’s receptiveness to absurd ideas. Instead, it’s time for cooler heads from across the political spectrum to work together to change the direction of U.S. policy toward Venezuela. First, U.S. citizens who care about Venezuela must organize to force Trump to lift his financial embargo; then we must encourage efforts to build trust and dialogue across the political divide while marginalizing hardliners who oppose any form of compromise.

Alexander Main is senior associate for international policy at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC.