On November 18, 2018, Taide Elena spoke movingly on the Mexican side of the border in Nogales to a group of border activists. She was speaking on behalf of her grandson, José Antonio Elena Rodriguez. In 2012, Border Patrol officer Lonnie Swartz killed José Antonio when he was 16 years old, shooting him 16 times in 34 seconds through the Nogales border wall. José Antonio was accused of throwing rocks over the wall, an almost impossible feat, given the height of the wall. “Even if he was throwing rocks, it isn’t fair. 10 shots to the back. But, there’s no video showing him throwing rocks. He left a distraught family. He left a deep hole in our hearts that will last a lifetime. And the pain that you feel in your heart, in your soul, is much deeper than what you feel in your body because when you have a pain in your heart, you can’t fix it with a Tylenol or an Aspirin,” said Elena, her voice breaking as she fought back tears. In April 2018, a jury found Swartz not guilty of second-degree murder, but could not agree on the verdict for a lesser voluntary manslaughter charge. In late November, a few weeks after Elena’s speech, Swartz was found not guilty of involuntary manslaughter, though the jury has still not come to a decision on voluntary manslaughter.

Elena’s speech was a testament to the direct effects of U.S. border militarization on her family. She gave the speech during the 2018 School of the Americas Watch (SOAW) cross-border Encuentro, held on November 16-18, 2018 in Nogales, Sonora and Nogales, Arizona. The first SOAW vigil was held in 1990, after six Jesuits, their housekeeper, and her daughter were murdered in El Salvador, and graduates of the School of Americas (SOA) military training camp were implicated in their murders. About a dozen activists attended that first vigil, called by Roy Bourgeois, then a Maryknoll priest. For years, the annual SOAW action was held in Fort Benning, Georgia, where the SOA training base is located. In 2001, the school was renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC). In the past, SOAW activists used Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to try to identify Latin American police and military trained at SOA/WHINSEC who then ordered, oversaw, or were directly implicated in atrocities in their home countries. These requests have been summarily denied.

In 2016, SOAW moved their yearly vigil to the Nogales Arizona/Sonora border because the U.S./Mexico border zone is an urgent site of U.S. militarization and oppressive state policies in the Americas. This move sought “to call attention to militarized U.S. foreign policy as a principal root cause of migration, as well as the devastating impact U.S. security and immigration policy has on refugees, asylum seekers and immigrant families all over the continent,” as their website attests.

The number of attendees at the annual vigil reached a high of about 22,000 in 2006, but has decreased in recent years. This year, attendance in Nogales was under 1,000. Its attendees see the Encuentro as a powerful space for building community, educating themselves about the reality of U.S. border militarization, and showing transnational solidarity with migrants. Considering the violence and harassment that Central American migrants are currently confronting at the U.S/Mexico border in Tijuana—reflective of their treatment over the past several decades—the need for binational, trans-border resistance is dire. The 2018 SOAW Encuentro provided a space for mourning, healing, and sharing of strategies for organization and resistance.

Sharing Across the Wall

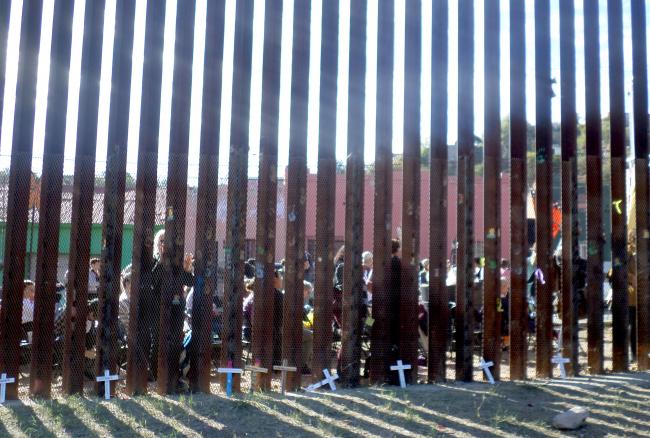

The border wall in Nogales isn’t a solid concrete wall, like it is in Palestine. It is a slatted wall, through which you can pass things and talk. In previous years, I have spoken with families sitting on folding chairs on both sides of the border while enjoying a meal together and catching up on family news. I have spoken with young couples trying to maintain relationships, who hold hands through the slats.

However, it has become much more difficult to meet with family members at the border in the past year. Now, a chain link fence has been attached to the slatted border wall and a wide “no-man’s land” has been established between the wall and the road on the U.S. side—which is ironically called International Street on both sides of the border. There is now also barbed wire on top of the wall. According to residents on both sides of the border, the barbed wire was added to the top of the wall right before this year’s Border Encuentro.

Despite these increased border militarization efforts, the Border Encuentro in Nogales consisted of people coming and meeting to share across the wall, from both sides of the U.S./Mexico border. Because there are checkpoints north of Nogales, this affected the number of people who could attend the Border Encuentro—attendees on the U.S. side of the border were typically documented. Activists from very diverse ethnic, gender, faith, ages, and socioeconomic backgrounds came to denounce U.S. military, economic, and political intervention in Latin America, which has contributed to the exodus of hundreds of thousands of people from their home countries.

The Encuentro’s programming included testimonies and short speeches, workshops and panels, and an evening concert on both sides of the wall. The testimonies and speeches were held on a small stage on the Mexican side of the border; on the U.S. side, speakers used a microphone as this year, SOAW was not allowed to place a stage on the U.S. side or occupy the new “no-man’s land” next to the border wall. The workshops and panels in Nogales, Sonora were held in an elementary school and tents next to the border; while in Nogales, Arizona, they were held in rooms and tents at the Americana Hotel, headquarters of the Border Encuentro. Walking through the border crossing into Mexico was quick and easy, as it involved simply walking through a turnstile. However, the return trip was often arduous and very time-consuming. Some attendees reported having to wait in line for three hours to do so.

Attendees emphasized what they learned in the cross-border workshops. “Going to the workshops and learning how the U.S. creates the conditions that make people come over here. How we Americans make these problems,” said university student Monica Rodríguez. “Making connections between U.S. imperialism and migration. I was aware of some of it, but it all came together [at the Encuentro].”

Vigil at the Eloy Detention Center

Beyond the workshops, a major part of the Encuentro was related to resistance against immigrant detention. In fact, on the first day of the Encuentro, about 400 activists of all ages and many ethnicities gathered across the road from the detention center for a vigil in front of the Eloy Detention Center, located about 100 miles northwest of Nogales, Arizona. It is a huge concrete building in the middle of the desert, with a single Saguaro cactus at the top of the driveway leading onto the property. It houses well over 1,000 migrants, many of them Central Americans seeking asylum. The Border Encuentro has incorporated a vigil at the detention center into each of its three years in Nogales.

Seven police SUVs blocked the entrance to the detention center driveway as participants sang, chanted, and listened to short testimonies and speeches. Their voices carried through the cool night air as they sang and chanted, for example, “Paz, queremos paz y libertad en este mundo” (“Peace, we want peace and freedom in this world.”) Across the street, the detention center began to light up. “You see the prisoners in the windows in orange jumpsuits being treated like criminals. That is so ugly. It’s disheartening. It’s angering. They’re behind bars when they’re trying to make a better life,” said Deja Alewine, a graduate student.

Other participants shared these sentiments, particularly students from Central American backgrounds, who made direct connections to their own family experiences. “For us, Central Americans and Latinx, the most powerful was the vigil at Eloy Detention Center,” said Arlette Jácome. “We could walk in front of the Detention Center and make our presence felt. Acknowledging that they are in there. Being able to be present for them. To show our pride and solidarity,” she said. “We saw that they were flickering their lights, waving something at the windows, a towel or a blanket, so that we could see that they saw us.”

Mourning as Resistance

The Encuentro culminated on Sunday, November 19, when people met once again on both sides of the border. There were more testimonies and short speeches, children performing on the Mexican side of the border, followed by a litany. The litany involved people on the stage taking turns reading about interconnected issues that are related to U.S. policy and actions. For example, members of the Tohono O’odham Nation spoke about how the border wall, which crosses their reservation, one of the largest in the U.S., is threatening their existence. Others noted how U.S. and Israeli military technology, developed by companies such as Boeing and Elbit Systems, is used to surveil, control, and kill native people and migrants. Not only that, but radioactive towers and walls have had negative impacts on the flora and fauna in the borderlands. The speakers denounced Islamophobia and the U.S.-led drug war, which has led to the surveillance and targeting of human rights defenders, reporters, and social movement leaders in Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and beyond. These speeches highlighted the ways that U.S. policy has adversely affected local populations, such as in Honduras through its support of the 2009 military coup, in Guatemala, where it supported dictator General Efraín Rios Montt, responsible for genocide, and in El Salvador, through funding the training of soldiers who assassinated Archbishop Oscar Romero and led death squads.

Next, singers on the stage called out the names of people who have died in the desert while coming to or crossing the border. Vigil participants called out “¡Presente!” (“here!”) after each name, while raising crosses with the names of victims on them or raising a fist in solidarity. This was followed by a symbolic funeral procession to honor the thousands of people who have died coming to the southern border.

“It was really heartbreaking and anchoring because I think it’s really important for us to realize that the U.S. policy in Latin America is responsible for this,” said Carla Valdivia, reflecting on the events. “Last year, I would hear their names, but I was thinking, why are these people dying? But, this year, I understood that the U.S. was behind it,” she said.

Why Continue to Go?

The SOAW Border Encuentro continues to be a vital site of trans-border and binational resistance because it brings together testimony, education, and organizing in an environment of cross-border sharing—which is, in itself, an act of resistance.

Border Encuentro attendees commented on how it offers an opportunity to express resistance to U.S. militarization and intervention around the world; to make connections and build community among people who share similar concerns; and to help people become better informed and more clear and focused about their next steps in resistance.

Bob Nixon was invited to his first vigil in 2000 by Fr. Bill O’Donnell, an activist priest who died in 2003. “Why go back? The meanness of so much of this and how it impacts all kinds of people,” said Nixon. He also thinks the Border Encuentro is particularly powerful because it attracts more young people and people with roots in Latin America.

For some, it felt that the urgent need was currently at the border in Tijuana, not Nogales. “I think it (the Border Encuentro) brought people together from across the nation, which is important because we are often working in isolation,” said Arlette Jácome. “[But], as a Central American, my mind was on the Exodus. I wanted to be in Tijuana. That was difficult.”

Nevertheless, the SOAW Encuentro remains an urgent space of solidarity and resistance. Monica Rodriguez’ family is from Central America and one of her comments captures what so many people expressed. “Last year, it turned on the activist side of me. Going again, it reassured me that this is why I’m here. Continuing to find ways to be in solidarity with my community. We’re showing we aren’t going to stand by and let you throw people out of the country,” she said.

Katharine Davies Samway is a freelance reporter.