This December, we are asking readers to make a tax-deductible contribution before the year is over to ensure NACLA continues to provide only the best in progressive news and analysis on Latin America. Visit nacla.org/donate

On November 25, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, hundreds of women gathered around the Chilean capital of Santiago to denounce gendered violence. The women danced to a synchronized choreography while declaring with one voice, “¡Y la culpa no era mía, ni dónde estaba ni cómo vestía!” (And it was not my fault, or where I was, or how I was dressed!) Shifting the blame away from women who experience sexual violence and onto the state, they pointed to functionaries such as police, judges, and the president declaring, “¡El violador eres tú!” (The rapist is you!) Pumping their fists in the air the women chanted, “¡El estado opresor es un macho violador! (The oppressive state is a male rapist!). The protest, named “Un Violador en tu camino,” went viral.

The performance was the brainchild of lastesis, a feminist collective founded by Dafne Valdés, Paula Cometa, Sibila Sotomayor, and Lea Cáceres, four women from Valparaíso, Chile. According to the founders, the collective uses performance in order to translate feminist theories to the public, such as those of anthropologist Rita Segato, whose work on sexual violence as a political phenomenon inspired “Un violador en tu camino,” and Marxist feminist Silvia Federici. In addition to being a form of popular pedagogy that uses performance to make feminist theory more accessible, “Un violador en tu Camino” speaks to the violence that women participating in the Chilean anti-austerity protests encounter at the hands of the police. They wear blindfolds as a nod to the widespread blinding of protesters. At one point, the performers squat down to mimic the stance women are forced to assume upon arrest. “During the protests there exists the possibility that the police will torture you, that they strip you naked or they rape you,” the members of lastesis explain. Indeed, Human Rights Watch has documented widespread police abuse, including sexual assault, during the Chilean protests against austerity.

Although the song speaks to the particularities of gendered violence arising from the recent protests in Chile, the song has struck a chord around the globe, spawning performances in Peru, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Spain, France, Germany, England, Mexico, Lebanon, and India, just to name a few. Recently, women from the Republican People’s Party (CHP) performed a rendition of the song in the Turkish parliament, banging on their desks and holding pictures of 20 victims of femicide while denouncing gendered violence as well as widespread political repression. The song and accompanying performances have become viral sensations with videos getting millions of views on various media platforms. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez recently tweeted about the performances and declared her solidarity with feminists in Chile. As the performance started to circulate like wildfire, one Twitter user joked, “Confirm that you all also have ‘y la culpa no era mía, ni dónde estaba ni como vestía’ stuck in your heads,” while another said, “If I don’t hear “El Violador Eres Tu” w that Pitbull beat under it at the club before the year is out I’m gonna riot.” How does a song about the ubiquity of sexual and gendered violence perpetrated by the state against women become an earworm?

“Un violador en tu camino” has gone viral and become a global phenomenon because violence against women is a global phenomenon.

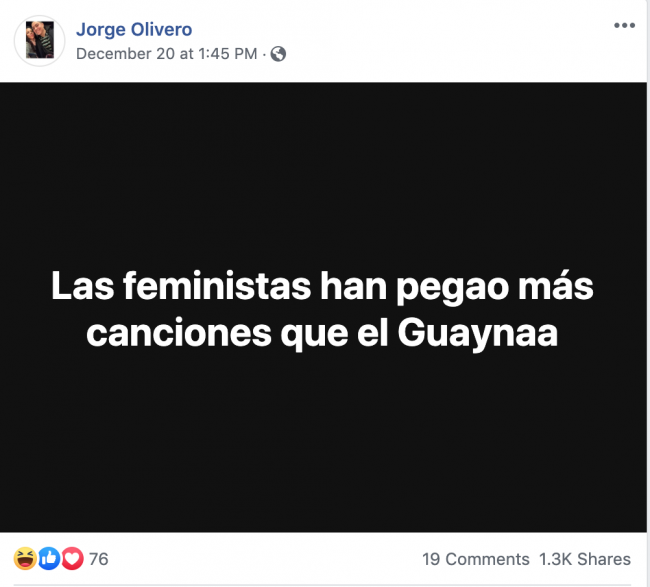

Similar to how the performance of “Un violador en tu camino” intervenes in public spaces, forcing passersby to confront the violence that women endure, the virality of the recorded videos causes it to erupt in social media feeds, making users engage with the spectacle of protest. “Un violador en tu camino” went viral not only through the circulation of videos but also through memes and social media repetition. Following the tradition of comic strips, banners, graffiti, and other forms of protest art, this year’s global protests have used memes not only to make light of detractors and satirize tyrannical leaders and politicians, but to offer pedagogical lessons. Global alt-right and fascist groups have long used memes to mock and undermine leftist and liberal demands. Despite ofand possibly, due tothis, young activists, amongst them feminists, have re-politicized memes as another form of engagement that, beyond showing discontent, strengthens the work of protesters on the ground and counters the disparagement produced by conservative groups. In the case of the Chilean feminist protests, the memes related to “Un violador en tu camino,” which often remix the song, remark on the infectiousness of the chant and transform it into an object of popular culture.

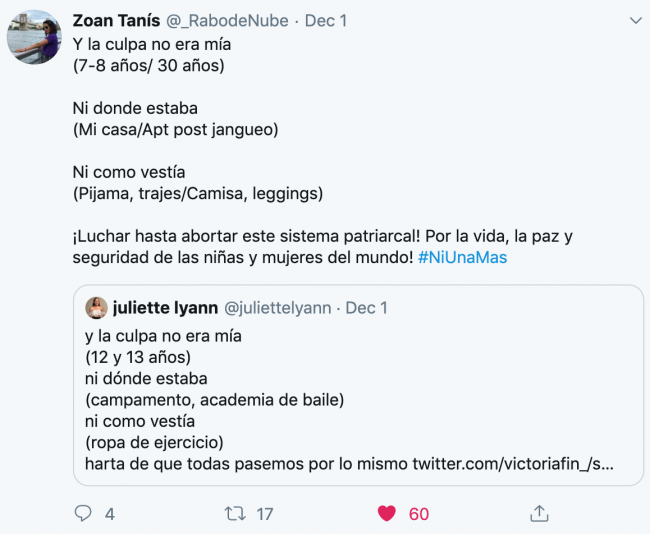

On social media, women have also broken down the lyrics in order to share moments when they have experienced sexual violence, sharing their ages, where they were, and what they were wearing in order to challenge the idea that the abuse they suffered was somehow their responsibility. The strategy of copy and pasting the lyrics in order to share these experiences and say “me too” creates a sense of solidarity and reminds women who have experienced sexual violence that they are not alone. Social media’s adaptation of “Un violador en tu camino” becomes a mode for resignifying norms around how gendered and sexual violence are conceptualized: Rather than a private problem of morality and comportment that is shameful and must remain hidden, it is a problem of a state apparatus that participates in and facilitates violence against women at a variety of scales that must be confronted in the open. This resignification on social media becomes a skillful strategy that places the song and its message into wider circulation. If memes are by definition a continuous hijacking of ideas and content in a way that makes them recognizable and instantly relatable, we can read the viralization of “Un violador en tu camino” in Chile and other sites around the globe as a feminist appropriation of protest performances that reframes and enhances the original discourse to amplify local struggles.

In Puerto Rico, for instance, feminists have capitalized on the virality of “Un violador en tu camino” in order to bring attention to the ongoing local struggle against femicides and colonial exploitation and to advocate for education with a gender perspective. At least three performances have taken place in different sites of San Juan, including in front of the Capitol building and on Calle Fortaleza, the street leading to the Governor’s Mansion where thousands of protesters gathered to demand #RickyRenuncia during the summer of 2019. Like their Chilean counterparts, these performances worked to reorient the narrative about sexual and gender-based violence from an interpersonal one to one of state violence. The first performance, organized by The Colectivo Educativo por la Perspectiva de Género (CEPG) took place on November 29, and implicated Governor Wanda Vázquez, the Senate, and U.S colonialism as culprits in the perpetuation of violence against women by adding lyrics specific to the Puerto Rican context: “¡Son los puercos, es el Senado, es la colonia, es Wanda Vázquez. El Estado opresor es un macho violador!” (It’s the pigs, it’s the Senate, it’s the colony, it’s Wanda Vázquez. The oppressive state is a male rapist!)

During the most recent iterations, which were organized by the choreographer Petra Brava and performed on December 20, protesters used the lyrics to address collaboration between government and religious organizations to silence discussions of gender and sexual difference and block education with a gender perspective. Together, the state and religious conservatives create policies and norms that that devalue the lives of women: “La culpa es del silencio y una mala educación, la culpa es del gobierno, las iglesias y su infierno.” (The silence and bad education, the government, the churches and their hell, are to blame.) Beyond the added lyrics, these Puerto Rican performances connect the Chilean women’s embodied articulations of violence with long-standing feminist struggles in the archipelago through specific public usages of the body. These adaptations of “Un violador en tu camino” are particularly poignant as they come after the release of a report implicating the police and local government in the high rate of femicides in Puerto Rico.

This musical detail acknowledges the interconnectedness of feminist struggles with racial and class ones.

In the initial Puerto Rican adaptation of “Un violador en tu camino,” CEPG altered the original concluding lines from a critique of the “carabineros,” or Chilean police, to one aimed at girls who might see the performance or hear the song: “Duerme tranquila, niña inocente, sin preocuparte del charlatán, que por tus sueños, dulce y sonriente, donde te encuentres las feministas vamos a luchar.” (Sleep peacefully, innocent girl, without worrying about the charlatan, because wherever you are, for your sweet dreams, us feminists will fight.) The adaptations and virality of “Un violador en tu camino” circulate not only as a demand for accountability from the state but as a promise to women and girls that together feminists will fight for a future free from gendered and sexual violence. The virality of “Un violador en tu camino” has benefited local feminist activism worldwide by placing regional groups under the public eye. The demands of feminists from the Global South can gain strength not only through the symbolic solidarity that these assemblages provide, but by calling attention to the specific structural conditions that affect women, causing the performance to resonate in the first place.

Verónica Dávila Ellis is a PhD candidate in Spanish and Portuguese at Northwestern University researching sound and gender performance in female and queer reggaetón.

Marisol LeBrón is an Assistant Professor of Mexican American and Latina/o Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Policing Life and Death: Race, Violence, and Resistance in Puerto Rico and co-editor of Aftershocks of Disaster: Puerto Rico Before and After the Storm.