It took a few visits for Javier Castaño, editor of Queens Latino, to connect with homeless Mexican immigrants sleeping under a highway in Jackson Heights. The immigrant workers had lost their construction jobs during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic and had to sell all they had to survive. Covid-19 had ravaged Queens, with Elmhurst as its epicenter of New York City’s outbreak in April.

Queens Latino, a local Spanish-language publication, has been covering the impact of the deadly virus on the borough’s mostly immigrant working community, many of whom are undocumented. In May, Castaño observed the growing population of unemployed immigrants living on the streets and under highways.

He had visited the site one morning to view the conditions, and returned later in the week to introduce himself and chat with the workers in Spanish while his car was being repaired nearby. After he picked up his vehicle, he returned to spend more time. “We talked about life, and we laughed together.”

As a rapport grew, Castaño told them that he was a reporter and asked them if he could video their conversation. “They said yes and kept answering my questions.” They told him they had nothing left to live on. “Trabajo se paralizó y no tenemos nada,” Adam Garcia told Castaño. “No tenemos ni un peso para comer, solo lo que nos regalan.” (“Work has ground to a halt and we don’t have anything. We don’t have any money to eatwe only have what people give us.”)

The raw interview gave readers a glimpse into the desperation that the most vulnerable immigrants in Queens face in the age of Covid-19. His local reporting showed there were many more mostly impoverished immigrants out of work, and he expected the problem to get worse. “By the first of June, people will have to pay rent, and the problem of homelessness isn’t going away,” Castaño said.

Covering a Community in Crisis

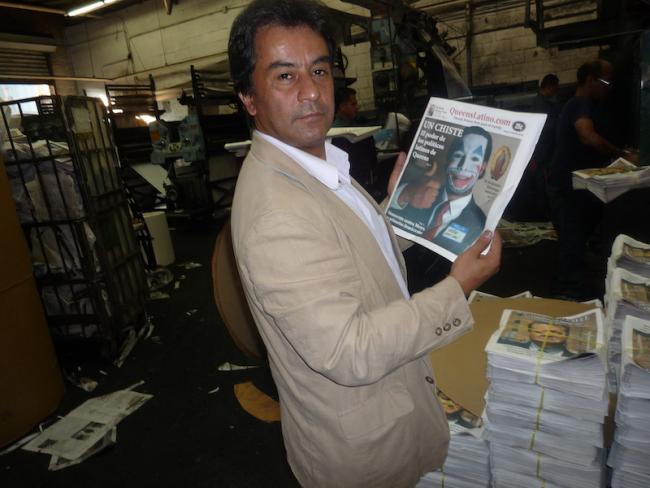

Despite the risk of street reporting during a pandemic, Castaño sees deep community coverage as Queens Latino’s primary mission. Latinos comprise 28 percent of the borough’s population, and they hail from more than a dozen Latin American countries, including Ecuador, Mexico, Colombia, and Peru. Castaño founded the Queens Latino platform in June 2010 as a website featuring news affecting local Latinos, and later added a newspaper and social media. His wife does the layout and design.

With a 25,000-circulation free monthly paper and a website with 2,000 daily unique visitors, Queens Latino has been publishing local stories from politics to parades for 10 years this month. But covering Covid-19’s deadly spread in the densely populated and mostly immigrant Latino neighborhoods of Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, and Corona proved to be Queens Latino’s most challenging assignment.

Since the explosion of novel coronavirus cases that made Elmhurst the early epicenter in New York City, Queens Latino has chronicled Covid-19’s disproportionate impact on Latinos during the peak outbreak months of March, April, and May. Latinos accounted for 34 percent of Covid-19 deaths citywide in early April at the height of the pandemic and remained consistent through mid-May.

Finding freelancers willing to work during the pandemic became difficult so Castaño, a seasoned journalist of more than 35 years who launched his career in his native Colombia and later in New York City’s Spanish-language press corp, hit the streets himself to report. At the height of the outbreak this spring, Queens Latino became a vital source of reporting on the many complex health and social problems that immigrants face, while connecting the community to resources they needed to survive the deadly virus.

“At the beginning, we focused on health and we interviewed people who got sick, highlighted those Latinos who died and tried to explain why they were dying,” Castaño said. “Then we switched to the food problem and how they could get food and where, and then we covered the homeless. Now, the coverage is focusing on how to reopen businesses.”

In Queens, many immigrants are essential workers: mostly newcomers who are navigating a complex system in a foreign country with little or no command of English. They work in construction, hospital, and cleaning jobs, and could not afford to quarantine.

“They live in overcrowded apartments, and they have to go out to get money and so they have to go to work. They deliver food, others cook, and some are still cleaning places,” Castaño said. “They have to go out.”

It’s been Castaño’s mostly old-school shoe-leather reporting that put a face on the pandemic’s deadliest impact in March, April, and May: profiles of the locals who died, images of families mourning socially-distanced in funeral parlors, interviews with the unemployed waiting on food lines and an exclusive with the pulmonologist who saw an overwhelming number of patients at Elmhurst Hospital.

Stories from the Covid Trenches

By mid-June, the Covid-19 virus had claimed more than 100,000 lives in the United States, and more than 5,200 confirmed deaths in Queens, more than 1,000 in Corona, Elmhurst, and Jackson Heights. Through the spring, Queens Latino‘s front pages documented the surge in cases when Elmhurst was ground zero for the exploding pandemic.

In its March edition, Queens Latino warned readers to guard against contracting Covid-19 and published information about the health protocols of frequent handwashing, social distancing, and face coverings. But it was the April issue that reported Covid-19’s grip on the mostly Latino population as hundreds of cases filled Elmhurst Hospital’s critical care unit. Queens Latino’s striking photo of a body on a gurney with a one word headlineAUXILIO (Help)told the story of a community in crisis.

Dr. Alfredo Astua, who oversees Elmhurst Hospital’s critical pulmonary care, told Castaño recently, his unit typically treats from 12 to 14 patients per year and monitors eight ventilators. During the surge of the Covid-19 pandemic in April, they saw as many as 100 patients at a time and monitored 170 ventilators.

With cases significantly down in May, Astua, who is from Nicaragua, encouraged immigrants to continue hygiene and social distancing, and also seek primary care for routine ailments, such as high blood pressure, as an added defense against any second wave of the virus.

Hopes for Reopening, but Need Persists

As the city prepared for a calculated reopening in June, Queens Latino’s May headline read, “Hambre en Queens” (Hunger in Queens). Castaño reported from the long lines where the unemployed and needy waited with their shopping carts for donated food that often ran out.

“Everybody is looking for a job or planning to open the store or restaurant,” Castaño said. “When you interview people on the food line, that’s all they think about.”

Many of the unemployed worked in the hospitality or restaurant or small mom and pop businesses that suffered financial losses during the quarantine. A March survey of 1,000 New York City residents conducted by the City University of New York’s Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy found that 41 percent of the Latinx/Hispanic community said that either they or a household member had lost their jobs. This compared with 24 percent of (non-Latino) white and Asian respondents, and 15 percent of Black respondents.

Many small Latino bars and restaurants that Roosevelt Avenue and other main streets in Queens are not likely to return unless the businesses have been established and proprietors own their buildings, Castaño estimated.

Many immigrants did not qualify for the federal stimulus aid because of their immigration status. They have been asking about an Open Society Foundations’ $20 million grant in partnership with the city, which could help the undocumented with a few hundred dollars. Queens Latino has reported on the grants and pressed officials about the distribution of the funds.

At a time when community papers are dwindling across the country, Queens Latino‘s editor says the pandemic gives local news a greater role. Castaño noted a deepening digital divide that is now making information online increasingly inaccessible to unemployed immigrants.

“If you don’t have money to pay the rent, how are you going to be connected?” Castaño said. “That’s why community newspapers have more value now more than ever.”

Edna Negrón is a professor of journalism at Ramapo College of New Jersey. Her research interests are community journalism and Latinx issues. She is a long-time journalist and has worked at New York Newsday, The Sun-Sentinel in South Florida, and The Record in North Jersey.