This is the second article in series on child migration from the Infancias y Migración Working Group. You can read the first here. We’ll have a new article every Friday.

On May 17, 1972, Border Patrol agents in Guadalupe, California detained an undocumented Mexican worker and expeditiously scheduled him for “departure” from the United States. His deportation order for May 19 came just one day before a public meeting on the issue of discrimination in the Guadalupe Union School District. It was a case of state-sponsored retaliation. He had been fired from his job of more than two years at a local dairy farm and apprehended by federal immigration authorities for protesting insidious practices in the administration of a program for migrant students and demanding that his two children be provided a safe, non-discriminatory schooling environment.

The implementation in 1965 of the Migrant Education Program (MEP), a federal education policy aimed at ensuring access to quality schooling for the children of migrant workers, had created a little-known data collection technology that stored intelligence that could be used to quickly locate migrant students’ families. Despite its originally good intentions, the MEP ended up producing novel forms of precarity for the growing numbers of undocumented children and parents that ended up in U.S. public schools in the 1970s.

This late-20th century data collection helped to transform schools into early school-to-deportation pipelines. Debates around migrant children revealed that the politics of childhood can be wielded for vastly different ends—ranging from humanitarian to punitive—in a single moment in time, a phenomenon that continues to have reverberations today. Divergent conceptions about migrant minors exposed the extreme malleability of childhood innocence and, ultimately, its racial exclusivity.

Even though the majority of Latin American immigrants to the United States during the 1970s were adult males, children increasingly migrated or were brought north in search of family unity, educational opportunities, work, and safety after 1965. The termination of the guestworker Bracero Program and the passage of the 1965 Hart-Celler Act severely limited the availability of lawful avenues for migration, causing millions of Mexican adults and children to enter the United States without authorization. In fact, it was during the ‘70s and ‘80s that immigration authorities started to immediately incarcerate unaccompanied minors in immigrant detention centers and jails.

At the time, the educational enrollments of undocumented children, which was estimated to be at least 40,000 in California and anywhere between 20,000 to 120,000 in Texas, inspired deeply contradictory responses from U.S. citizens, local child welfare advocates, and liberal policymakers.

In 1966, for example, a private U.S. citizen wrote to the California Department of Education to denounce the MEP because he alleged it represented a “multi-million dollar fraudulent scheme” imposed on U.S. taxpayers for the benefit of “Mexican aliens.” He attached significant culpability for this “fraud” to undocumented Mexican youth, whom he claimed belonged to a criminal organization called the “M.A.F.I.A.,” which stood for “Mexican-American Fraud in America.” This kind of xenophobia was rooted in the longstanding racialization of the invading “wetback,” which extended to minors and didn’t even spare infants.

When directed at children, this anti-immigrant vitriol denied minors the privilege of childhood innocence and instead portrayed them as menacing and inherently criminal. They were treated not as defenseless kids but as young people more akin to adults. Depicted in this way, migrant youth become seen as capable of committing fraud to gain entry to the nation and as serious threats to its society and social safety net.

Unlike the immigration opponents behind such fraud claims, the grassroots advocates and teachers who conceived of the MEP viewed migrant youth with and without U.S. citizenship in entirely different terms. Migrant education advocates sentimentalized childhood as inherently innocent. They believed adults had a moral responsibility to shelter defenseless kids from the adult worlds of work and punishment by ensuring migrant children could safely remain in schools—an early version of sorts of the #SchoolsNotPrisons movement.

Good Intentions Take a Nefarious Turn

The well-intentioned teachers and child welfare advocates who rejected the criminalization of migrant youth wrapped their advocacy in a race-neutral politics of childhood and successfully lobbied Congress to include the MEP in Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. They cited migrants’ status as “the most educationally deprived group of children in our nation” and the need to restore their sense of an “active childhood.”

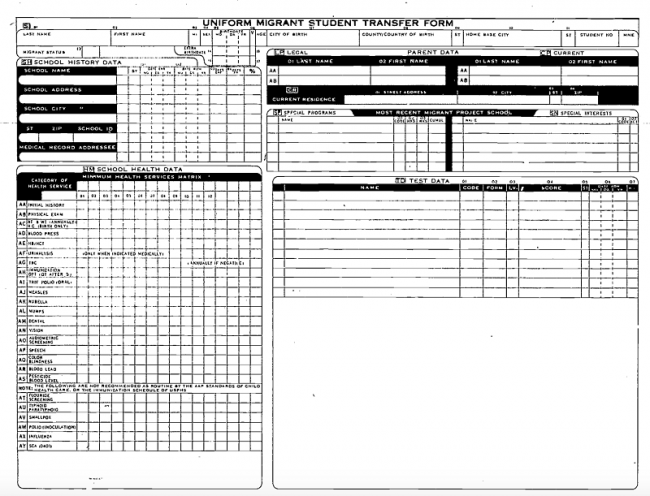

What grassroots education advocates did not anticipate, however, was that the MEP’s introduction of a unique computerized data collection technology in primary and secondary education would be refashioned for nefarious purposes. This federal data bank, known as the Migrant Student Record Transfer System (MSRTS), stored personal data about migrant youth and their parents, including birthplaces, home addresses, migration patterns, and medical and academic histories, on a central computer with no clear or enforceable procedures to protect migrants’ privacy.

By gathering intelligence and reproducing anti-immigrant attitudes inside school walls, the MSRTS enabled local police and federal immigration agents to detect migrant youth and their parents, transforming schools into arms of the immigration regime and sites of carceral surveillance. The California Education Code enabled school administrators to expel students from schools if they determined the child lacked legal immigration status. The Education Code also required school officials to report undocumented students to local law enforcement agencies and federal immigration authorities. In 1975, Texas created a law permitting school districts to deny undocumented children educational access, and in 1980, the state legislature seriously considered a mandatory reporting law like California’s, which would have equipped school personnel with the power to report students to immigration authorities. The expulsion and information-sharing provisions of state education laws were twin features of late-20th century school-to-deportation pipelines. They facilitated a double removal of undocumented children: first from schools and then from the nation.

MSRTS data collection was weaponized to surveil migrant children and their undocumented parents, whom education authorities saw in racial stereotypes that marked them as violent. A 1973 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report revealed that some California schools, for example, refused migrant children forks at lunch and explained this policy by asking, “How can you expect children to use forks if they use tortillas at home? And they’d just use them to stab one another.” These fears helped justify school administrators’ advice for counselors to “share [their] complaints with police and welfare agencies.” In fact, internal policy memos of the California Department of Education’s legal office allowed for the transfer of MSRTS files, specifically, to law enforcement.

Deploying the Politics of Childhood Innocence

When noncitizen parents and their children challenged the injurious practices of the MEP, they found themselves threatened with detention and deportation, like the father in Guadalupe. Depositions for educational litigation also revealed administrators’ commitment to calling the Border Patrol when school files revealed a child’s undocumented legal status.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, undocumented children in California and Texas challenged their unconstitutional school expulsions and schools’ transformation into deportation pipelines in state and federal courts. This legal advocacy culminated in the 1975 Maria v. Riles case, which invalidated California’s mandatory reporting laws, and the 1982 Supreme Court decision in Plyler v. Doe, which struck down the Texas law that expelled undocumented youth from schools.

The lawyers in Plyler developed arguments rooted in the politics of childhood to build a sympathetic defense against undocumented pupils’ educational deprivation and public schools’ transformation into sites of immigration enforcement. According to attorney correspondence, the trial strategy relied on the portrayal of “a warm picture of innocent human beings.” The plaintiffs’ young ages and the prevailing conception of childhood as fundamentally innocent, their lawyers hoped, would convince the Supreme Court that the undocumented children were “without fault” for their family’s irregular immigration status and their supposed abuse of U.S. social institutions.

This line of reasoning worked. Justice William J. Brennan’s Equal Protection analysis relied on the notion that undocumented youth were “innocent children” who could not “affect their parents’ conduct nor their own status.” Even though this presumption of childhood innocence has had the effect of preserving noncitizen children’s right to an education into the present day, it also helped to cement the idea that undocumented parents’ conduct was criminal. The “warm” portrayal of “innocent” school children succeeded in institutionalizing children’s role as rights-bearers at the expense of their adult parents.

The weaponization of childhood innocence to indict migrant parents’ brave and difficult decision-making has had far-reaching consequences. The 2018 “zero-tolerance policy” that separated children from their families by prosecuting parents for illegal entry was rooted in the notion that parents’ conduct was undeniably criminal.

To this day, migrant children’s access to the politics of childhood innocence is far from guaranteed. Plyler’s endorsement of undocumented young people’s innocence did not eradicate school-to-deportation pipelines, nor did it shield asylum-seeking children from immediate criminalization in immigrant detention, which reached unprecedented levels of apprehensions and violence in recent years.

The history of the school-to-deportation pipeline lays bare the double-edged sword that is the politics of childhood innocence. But understanding this history does more than expose xenophobes’ attitudes about border-crossing minors. It also suggests that contemporary immigration policies that rely on injuries to child or family welfare are not aberrations, but part of a much longer history of child migration. Rhetoric about childhood innocence requires close scrutiny, because its consequences can be just as insidious as that of the explicit criminalization of migrant childhood, and yet far more likely to fly under the radar.

Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez is a U.S. history Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University specializing in the 20th century legal history of child migration. Outside of the academy, she has conducted research on child migration for the federal government and non-profits in the U.S. and Mexico.

About the Working Group: In July 2020, the authors convened the Infancias y Migración Working Group, consisting of 10 colleagues in five countries from a variety of disciplines. This series of articles for NACLA is the group’s first publication project.