The same day President Nayib Bukele announced a strict lockdown for El Salvador at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, a collective of local women’s organizations launched a hotline to support women confined indoors with their abusers. The country was not prepared for the public health emergency nor for protecting women against violence. “Emergency situations,” the groups noted, always exacerbate “acts of violence against women stemming from existing inequalities.” By early June, the feminist organization Colectiva Feminista para el Desarrollo Local had documented 26 femicides during the lockdown.

In recent years, El Salvador has reported high rates of domestic violence and epidemic rates of femicide, the intentional killing of a woman or girl based on her gender identity. A 2017 survey found that 67 percent of Salvadoran women had experienced some form of violence in their lives, and in 2019, the country had one of the highest femicide rates in Latin America, second only to Honduras. Although El Salvador passed a gender violence law in 2011, establishing sentences of 20 to 50 years for femicide, acknowledging and prosecuting these cases remains arduous. The pandemic has further exposed these challenges, including by exacerbating structural barriers to reporting gender-based violence. Local human rights lawyers and feminist activists have been fighting to address these limitations by expanding support systems for victims of domestic violence.

Salvadoran law defines femicide as the killing of a woman with “motives of hatred or contempt for her condition as a woman.” Some scholars have proposed the term feminicide, rather than femicide, to underline the role of state negligence in these crimes and the intersection of power dynamics and cultural and socioeconomic factors.

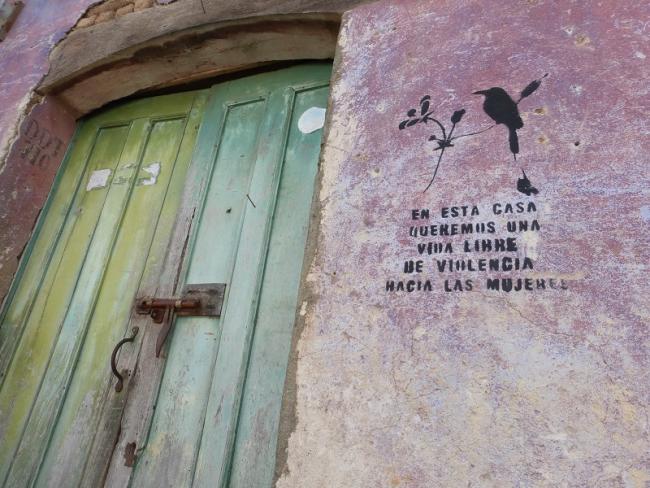

In El Salvador and elsewhere, most femicides happen within the context of domestic violence, and structural machismo and the societal normalization of gender-based violence perpetuate both abuses and impunity. Campaigns and events organized by groups like Colectiva Feminista aim to educate women on their human rights, improve their sense of agency and self-worth, and dismantle the normalization of violence. However, underreporting of domestic violence is still an issue.

“Domestic violence is the beginning [of feminicide] since women suffer domestic violence in silence,” explains human rights attorney Arnau Baulenas of the Instituto de Derechos Humanos de la Universidad Centroamericana (IDHUCA) in San Salvador. And according to Marshall University Latin America history professor Chris White, in El Salvador, a geographically small country with a high-density population, the normalization of violence is also shaped by a strong historical memory of civil war-era violence.

“Impunity Means More Violence”

Calling attention to the growing irregularity of resources available for women facing violence in 2020, Colectiva Feminista partnered with the abortion decriminalization organization Agrupación Ciudadana para la Despenalización del Aborto as well as the women’s human rights group Red Salvadoreña de Mujeres Defensoras de Derechos Humanos to create a hotline to provide psychological and legal support. The support line responds to an increased need since the start of the pandemic for remote resources for victims, their families, and others hoping to report instances of gender-based violence or gain information about preventative actions. Many callers are from family members and partners seeking legal assistance to press charges against their abusive counterparts, explains activist and lawyer Laura Moran.

According to Moran, the Colectiva Feminista received more gender-based violence cases in the first six months of the pandemic than it did during all of 2019. Reports to the police also increased during lockdown. However, uneven awareness among public officials about the problem, combined with normalization, has created significant barriers to building substantial legal services to protect victims of abuse.

Potential for revictimization by police who uphold patriarchal norms, such as the idea that domestic violence is a family matter, is one possible deterrent to reporting abuse. Such barriers to reporting, a lack of political will to dedicate resources to combatting feminicide, and structural problems in the judicial system also translate into a lack of justice for victims. Activists have often pointed out the hypocrisy of El Salvador’s justice system criminalizing women for having abortionsor stillbirths or miscarriages in many caseswhile failing to pursue prosecutions for femicides.

According to Baulenas, prosecutions are often overshadowed by personal and cultural biases against victims that color cases with patriarchal and machista assumptions. These biases contribute to impunity for gender-based crimes, and it can also retraumatize survivors who choose to report their abuse. “Impunity means more violence,” Baulenas explains, underlining a cycle of inaction that fuels further underreporting. “The system needs to be fixed and authority figures need reeducation,” he adds.

For Moran, raising awareness is an important first step in the broader ideological and cultural transformation required to meaningfully combat femicide and gender-based violence at the root. In the immediate term, on-the-ground responses like the Colectiva Feminista’s monitoring and the domestic violence hotline aim to create visibility for victims and provide support. They hope that breaking down the normalization of violence will in turn allow women to speak up about their abuse and seek help.

When Abuse Goes Unnoticed

President Nayib Bukele has smugly said that feminist groups should be “happy” with how rates of killings of women have fallen under his government. Although official data indicate that feminicide rates have declined since 2016, human rights groups highlight that other forms of violence against women, such as disappearances, have increased.

This dynamic recalls another period with a similar trend. In 2012, the Salvadoran government struck a deal with gangs to establish a ceasefire between the Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 in hopes of lowering homicides. As a result of the truce, the numbers of killings and feminicides did go down. According to a 2013 report by the international organization Interpeace, “immediately after the truce was agreed upon, homicide rates ostensibly decreased: 14 to 17 homicides a day dropped to an average of 5.5 deaths a day In parallel, there was also a decrease in femicides.”

Despite the controversy surrounding the trucenamely the government’s lack of transparency in secretive negotiationsthis reduction in killings was “one of the positive results,” a report by the Red Feminista Frente a la Violencia contra las Mujeres notes. “However,” the report adds, “it is necessary to deepen the analysis of the causes behind this decrease in violent deaths coupled with an increase in the number of acts of other forms of violence against women because femicides are a culmination in a continuum of violence.” The report also highlights that among the killings of women reported, most were carried out with “extreme cruelty,” and raises alarm that the generalized nature of this phenomenon has not received adequate attention. “The viciousness, hate, [and] torture go unnoticed,” it states.

Research has shown that it is not simply gang members inflicting violence against women; intimate partner violence generally is an important factor in and potential precursor to feminicide. Yet the country still centers tackling gang violence within its discourse as a tactic to counter high rates of feminicide. Focusing narrowly on so-called iron fist policiesheavy handed crackdowns resulting in mass arrests and incarceration of alleged gang membersnot only fails to remedy root problems but also may pull resources away from developing sustainable policies to protect women from domestic violence. Similarly, hate crimes against trans people and other members of the LGBTQI+ community is also a pressing issue that demands a targeted response beyond strategies that claim to address generalized violence.

Citing statistics from the attorney general’s office, Ormusa, a local nonprofit organization promoting women’s rights, reports that 130 women were murdered in 2020; this is a decrease from 238 in 2019. However, Baulenas warns people to be wary of government data because it could be motivated by electoral interests, such as the recent midterm elections, in which Bukele’s party won a majority. The decrease in femicide could reflect the fact that the state has not put enough resources into adequately investigating feminicide, especially considering that statistics show that other forms of violence against women have increased. According to Ormusa’s monitoring, cases of domestic violence in 2020 totaled 1,245, an increase from 1,172 cases in 2019. Moreover, feminicide statistics fail to account for the enforced disappearances of women and girls, and missing persons cases also raise questions about the possible underreporting of feminicide.

The “Other Underreported Pandemic”

Achieving a femicide conviction is difficult for two reasons, Baulenas says. First, there must be proof of an intimate relationship between the victim and perpetrator, which is difficult to prove. Second, many judges base their verdicts on personal biases, not an adherence to international law and treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication of Violence Against Women, also known as the Belém do Pará Convention. There is no guarantee that the appropriate laws will be applied every time. As a result, sometimes cases brought to trial as femicides are not tried as such, leading to impunity for this particular crime, Baulenas explains.

According to an investigation by Salvadoran media outlet El Faro, out of 3,000 women killed between 2012 and 2019, only 8.6 percent of cases resulted in a femicide prosecution. “If they weren’t killed for being women, why were they killed?” asked journalists Valeria Guzmán and Gabriela Cáceres. But their investigation found that “it’s almost impossible to give an answer in a country where more than half of cases go unpunished.” Their piece dubbed femicide the “other underreported pandemic.”

At a minimum, collaboration between various sectors is required to confront this complex problem. The economic and daily disturbances of Covid-19 have exacerbated issues of gender-based violence, which is a risk factor for femicide. Femicide’s place in these cycles of violence must be acknowledged to create better potential for intervention and prevention. Awareness is important, but only a first step.

SJ Fernandez, Yanxi Liu, and Kristina Zanziger graduated from Georgetown University with a Masters in Conflict Resolution. Fernandez concentrated on equitable solutions to identity-based conflict. She currently works within the Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion field in the nonprofit sector. Liu focused on human rights and gender-based violence in Latin America and political behavior/political engagement. Prior to Georgetown University, she worked for a development NGO in China with Poverty Alleviation Projects. Zanzinger specializes in human rights and social movements in Latin America with a research focus on LGBTQ+ and reproductive rights.