This is the third article in series on child migration from the Infancias y Migración Working Group. New articles go up on Fridays.

Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

The first wave of Guatemalan child refugees didn’t flee to the United States. They fled to Mexico. The trickle began a decade earlier, but the first mass exodus occurred between 1981 and 1982.

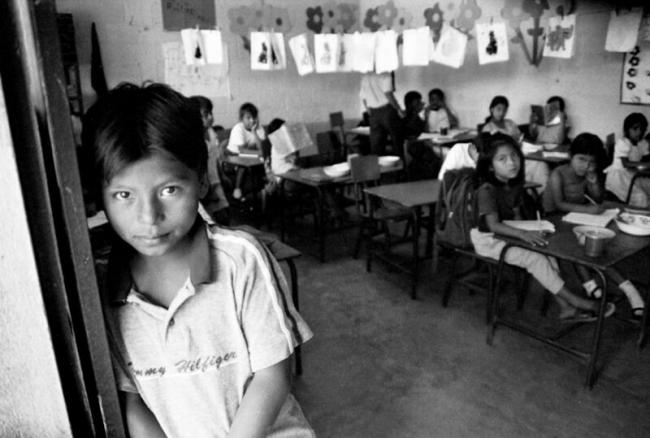

Guatemalan children at refugee camps in Mexico wrote essays explaining their experiences. One fifth grader wrote in response to the prompt, “Why did the Army first come to your village?”:

When they first came to the village, they were asking questions of people. Whether we knew any guerilla fighters. That was the only question they asked. The second time they came, they asked for papers. Whether we were citizens. Some of them were conscientious and asked nicely. Others accused us of being with the guerrilla. Those ones were already treating us with violence. The third time they came, they came with the purpose of killing the first person they killed in the village. That’s how the massacre started. When the people saw how the first person was killed, the people looked for ways to run.

The short text is full of spelling mistakes in the original Spanish, which resist translation. The child signed his school assignment, “Benigno Sales Cruz, Campamento La Flor.”

The name Sales is most common among Maya Mam people in Guatemala. Mam is one of 22 Indigenous languages spoken in Guatemala. The Mam people, along with K’iche’, Ixil, and other Indigenous groups were the target of the most extreme violence of the Guatemalan civil warthe genocidal army attacks of the early 1980s. Then, at Mexico’s southern border, as now, at Mexico’s northern border, a large proportion of child migrants were Maya. In a demographically young country where the genocidal state was explicitly targeting families and children, the civil war was an existential threat for children. Now street gangs are.

This earlier history of Guatemalan child refugees is completely absent in U.S. discussions of why Guatemalan children are arriving at our border, and the crimes now underway in the U.S. migration system.

Targeting Maya Children

The war had already been underway for nearly two decades. But in the 1980s, the Army turned its counterinsurgency campaign away from trade unionists and student organizers in the city to Maya families in the highlands, as the guerrilla moved from eastern Guatemala into the north and northwest. The military dictatorship became convinced, often wrongly, that Maya peoples were supporting the guerrilla. Declassified military documents show that the Army regarded the Indigenous family and Maya children as threats, as a breeding ground for what dictator Efraín Ríos Montt’s government called “bad seed.” Documents obtained by the National Security Archive show that the U.S. Embassy was aware that the Guatemalan Army was targeting children and families at this time.

After the war, a UN-backed Truth Commission found that the Guatemalan state had committed “genocidal acts” against Maya groups. In 2013, former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity, though the sentence was later overturned under political pressure. Evidence of his regime’s massacres and its crimes of stealing and disappearing children was presented at the trial.

One of the five possible components making up the legal definition of genocide is “Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” As Laura Briggs points out in her new book, Taking Children: A History of American Terror, that part of the definition has not always been fully taken into account in reckoning with genocides across the Americas.

At least 200,000 children were orphaned during the Guatemalan civil war, and an estimated 5,000 children were disappeared. In 1982, the government unleashed a series of scorched-earth campaigns and massacres in small, rural towns, like the village from which Benigno fled. In an appalling echo of MS-13 and Barrio 18, the street gangs that currently prey on Guatemalan children, young people were forced to flee or be conscripted.

Children caught by the Army were either impressed as child soldiers, stolen as domestic servants, orin up to 500 cases documented by the UN-backed postwar Truth Commission”children of the war” were put up for adoption through state orphanages, often abroad. Tens of thousands more children, during and after the war, were put up for adoption through a private system run by Guatemalan lawyers. At refugee camps and more permanent settlements in Mexico, children were more likely to remain within and be raised in their ethnic and linguistic groups by neighbors or members of their extended family, even if they had been orphaned.

Documenting Refugee Life

Benigno Sales Cruz’s school assignment, along with a whole set of papers related to this period of Guatemalan refugee life in Mexico, is preserved in an archive in San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chiapas. Archbishop Samuel Ruiz’s lobbying on behalf of refugees meant that these materials eventually ended up in a diocesan archive. (Ruiz may be familiar to readers of NACLA as a frequent nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize for his work with Indigenous communities in Southern Mexico, including helping to broker a ceasefire between Zapatistas and the Mexican state.)

The diocese’s solidarity committee organized a letter-writing campaign in 1983, gathering testimony from refugees to distribute to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the Mexican Commission for Aid to Refugees (COMAR) to help regularize the status of Guatemalans in Mexico. School assignments were part of this campaign.

Because Guatemalans had historically come to southern Mexico as seasonal workers for the coffee harvest, Mexico deported some early refugees. Advocates had to persuade the government to recognize that what was happening on their southern border was a refugee crisis, not the same old seasonal migration. Children at schools set up for Guatemalans wrote texts for the campaign, which bring up inevitable parallels with the present: fear, the lack of choice about whether to go or to stay, and proto-coyote figures who led Guatemalans to Mexico.

Benigno wrote another short text as part of a series of similar assignments, this time responding to the prompt “Describe your departure from Guatemala”:

At first my family did not dare to go because we didn’t know the way (no conosiamos los caminitos) that went to the border. But then a boy who lived in the village Agua Escondido in the same municipality showed up and we offered to pay him to lead us.

Another fifth grader, who signed his assignment only as “Brisanto,” fled without a guide. He recalled wandering the forest with his family for two days, hoping to stay hidden from the Army:

But then they found us and that’s how they started following us and shooting at us with their guns and by the time we felt that we were at the border of Mexico we were without clothes, without food, without absolutely anything.

An estimated 200,000 Guatemalans fled over the border to southern Mexico, though some estimates are far higher. The Mexican camps established for Guatemalan families during the most violent period of the civil war were the largest refugee camps in Latin American history. They were larger even than their counterparts in Honduras, which provided shelter to Salvadorans fleeing the violence of civil war and state terror. Scholar Susanne Jonas estimates that 46,000 Guatemalans lived in Mexico in UN-run camps, while the rest lived outside camps, either independently or on allotments provided by the Mexican government. Some refugees were officially documented, while others lived without papers in Mexico.

While the percentage of Guatemalan refugees in Mexico who were children is unknown, the archive reflects their ubiquitous presence. Children who had been orphaned or separated from their parents in the confusion of flight were often taken in by members of extended families or neighbors through informal adoptions, a practice common in many Maya communities even before the war.

In workbooks put together specially for use in classrooms in Mexican refugee camps for Guatemalans in 1984, the second-grade social studies unit had a unit called “The Family.” The workbook introduces the concept of the family, a mother and father’s responsibilities to take care of their children, and the chores a child was supposed to perform at home. Then the workbooks include a last section on orphaned children. Second graders were to read the following text out loud along with their teacher and classmates:

There are many children who don’t have their father, or their mother, or either of the two because they already died. These children are ORPHANS.

In our school and in the other schools for refugee children in Campeche [Mexican state to which refugees were relocated] there are many orphan children.

There are orphan children who only have a mother or only a father and their brothers and sisters. Other children only have brothers and sisters and live with another family.

The people who live with orphan children are their family now. These are the people who should care for, attend to, love, and raise the children and work so that they don’t lack for anything.

Children who are orphans should also help with chores and study at school.

Exercise:

Write a composition in your notebook about the topic of ORPHANS.

The Guatemalan and Mexican State Responses, 1980s to the Present

A major difference between refugees from the war and those seeking asylum today is that many Guatemalans were eventually granted official refugee status in Mexico. Another stunning difference is that in the 1980s Guatemala loudly clamored to get their refugees back. Today, the Guatemalan government is conspicuously silent as their migrant citizens are abused and denied rights in Mexico and the U.S. One factor in these differing responses is economic: most refugees in Mexico in the 1980s were unable to earn or save much money, and certainly not to send it to relatives who remained in Guatemala. Meanwhile as of 2017, remittances accounted for more than 11 percent of Guatemalan GDP.

Starting almost immediately after the first massive wave of refugees left in 1981, Guatemala lobbied hard for their return from Mexico. On the one hand, the Guatemalan government wanted the refugee families back as a global propaganda coup, as a sign that everything was all right in Guatemala at a time when human rights abuses were so rampant that even the U.S. had temporarily cut off military aid. In 1985, the Guatemalan First Lady visited Mexican refugee camps to convince Guatemalan families to return. On the other hand, the Guatemalan government continued to fear Maya families, though the systematic policy of “terminando la semilla,” (“terminating the seed” as it was characterized at the 2013 genocide trial), murdering and stealing children who they feared could later become revolutionaries, had ebbed in favor of more intermittent, though still terrifying, massacres.

The archive in San Cristóbal makes clear that the safety and future of child refugees and Guatemalan children generally were front of mind for adults in Mexico. Refugees wrote letters in the 1980s outlining the conditions they demanded to agree to return to Guatemala, including a “return of stolen children.”

While many adults decided to wait out the violence in Mexico, raising children in multilingual pan-Maya communities, others returned to Guatemala, often facing Army surveillance and harassment as the war dragged on. The first true mass return of Guatemalan refugee families from Mexico was in 1995, just a year before the peace accords were finally signed.

Mexico had a tradition of hospitality to asylum-seekers dating back to the Mexican Revolution. During the 1980s, despite initial resistance, Mexico eventually provided shelter and official refugee status to many Guatemalans, including children. Mexico’s attitude has since changed drastically.

Now, the U.S. has outsourced its border work to Mexico, especially since the signing of Programa Frontera Sur in 2014. Once again, there are camps in Mexico holding Guatemalan families and children. These refugee camps are temporary, unofficial, and located in the northern city of Matamoros, on the U.S. border. This is where the U.S. has expelled asylum seekers to await their hearings under the “Remain in Mexico” policy. During the pandemic, the U.S. has illegally expelled children from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador to Mexicoalone, with no accompanying adultin other words, to a country in which they have no family.

Mexico has not agreed to designate the area as an official refugee camp in collaboration with the UN, which then would have provided infrastructure. So, the camps in Matamoros have no housing, no sanitation, and unlike for Benigno, no schools.

Maya Families Continue to Flee

Many Central American families, including Guatemalans, report fleeing with their children to protect them. The New York Times recently reported from Matamoros: “Most children in the camp have not attended formal schooling since they left home. Parents agonize over whether they will be able to make up for the lost time.” When refugees flee from a gruesome war, at least since World War II, they have the hope and possibility of being recognized as refugees and being treated with some dignity. But when they try to escape gang violence, hunger, climate change, domestic violence, and all the overlapping monsters nipping at the heels of the Guatemalan families fleeing today, it is harder to gain recognition.

This history of Guatemalan child refugees is overlooked in U.S. discussion of current migrations, despite the fact that Salvadorans and Guatemalans are the largest groups of asylum seekers at the U.S. border today. Since the “unaccompanied minors crisis” starting in 2014, in many ways, Guatemalan out-migration has a similar face: Maya families and children, fleeing violence. A large though unknown percentage of current asylum-seekers are Maya families and children (ICE does not break down statistics by ethnic category.) While it is now mostly gang violence, not state violence, that pushes these people out of Guatemala, this distinction can be lost in a country where ex-generals have turned to narcotrafficking and privatized “security” work, and the government is ever more bought and even staffed by narcotraffickers and those who launder their money.

Guatemalans have longer memories, especially those who were caught up in the older patterns of migration, which involved dislocation and trauma, but also a political education. For example, Guatemala’s most prominent currently serving Maya Mam congresswoman, Vicenta Jerónimo, fled Guatemala with her family when she was 10 years old and grew up as a refugee in Mexico. After the Army launched cross-border attacks on a Guatemalan refugee camp in Chiapas, the Mexican government gave her family a house and a parcel of land in Quintana Roo. Like many other Guatemalan refugee girls in Mexico, she worked as a maid.

As a teenager, Jerónimo participated in the committees that negotiated and organized refugees’ return to Guatemala, lobbying for access to land for relocated families. Because of the war and the family’s repeated migrations, her access to school was patchy and she was barely able to finish second grade. She returned to Guatemala when she was 25 years old. In 2005, she was invited to a CODECA (campesino movement) meeting by another Maya Mam politician, Thelma Cabrera. Last year, Cabrera ran for president and earned 10 percent of the vote, the highest ever for an Indigenous politician, including Rigoberta Menchú. Though Cabrera grew up in Guatemala, the child of indigent coffee pickers, she was the only presidential candidate to talk about migration and the dignity of migrants.

Beyond Indigenous politicians and those who themselves escaped to Mexico, few draw the link between families of refugees in Mexico during the war and families attempting to access asylum in the U.S. now. But only by moving the chronology backward from the Obama Administration do the longer waves of anti-Indigenous violence come into view, along with the decades of ongoing displacement and dispossession of Indigenous and poor Guatemalans that built over generations and continue to fuel the flow of families to the U.S. border.

Driving through high-migration areas in Guatemala, you see billboards funded by the U.S. warning Guatemalan families not to endanger their children. The Embassy recently tweeted a message in Spanish saying: “Take care of your children. Don’t put them at risk with #illegalmigration.” The tweet was accompanied by a photo of Felipe Gómez Alonzo, an eight-year-old Maya Chuj boy who died in Border Patrol custody. The Embassy deleted the tweet after it was widely criticized for issuing what sounded very much like a threat. But this remains the official U.S. argument: Blame the parents.

But with a longer history in mindof the CIA-backed coup in 1954, state terror and genocide that the U.S. turned a blind eye to and indeed helped fund in the 1980sthe current effort to deter child and family migration looks like an attempt by the U.S. to stuff a genie back in the bottlea genie that the U.S. did more than its share in helping to create.

Rachel Nolan is an Assistant Professor at the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University. She is working on a book about the history of international adoptions from Guatemala.

About the Working Group: In July 2020, the authors convened the Infancias y Migración Working Group, consisting of 10 colleagues in five countries from a variety of disciplines. This series of articles for NACLA is the group’s first publication project. The previous articles are: Exiliados, Refugiados, Desplazados: Children and Migration Across the Americas and The Orgins of an Early School-to-Deportation Pipeline.