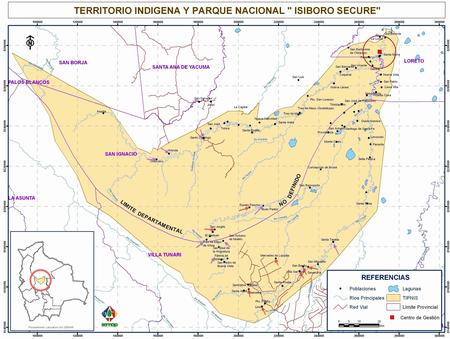

Leaders of lowland indigenous groups opposed to the Bolivian government’s proposed highway through the Isiboro-Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) warned last week that many communities will physically obstruct the consultation process mandated by the new law that President Evo Morales promulgated on February 10.

The announcement was strongly criticized by Senate president Gabriela Montaño, Senate President Gabriela Montaño. Credit: ABI Agencia. chief architect of the law establishing the first “free, prior, and informed” consultation process under Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution and international treaties, which the government views as a model for future conflict resolution in Bolivia and perhaps worldwide. “It’s the only democratic solution to the TIPNIS conflict [between pro- and anti-road sectors],” she stated. “Anyone who rejects the consulta is against the deepening of democracy.”

Senate President Gabriela Montaño. Credit: ABI Agencia. chief architect of the law establishing the first “free, prior, and informed” consultation process under Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution and international treaties, which the government views as a model for future conflict resolution in Bolivia and perhaps worldwide. “It’s the only democratic solution to the TIPNIS conflict [between pro- and anti-road sectors],” she stated. “Anyone who rejects the consulta is against the deepening of democracy.”

According to TIPNIS Subcentral leader Fernando Vargas, a “pre-consulta” carried out by his organization shows that 32 of 35 communities surveyed thus far are against the TIPNIS road. “If that is the correlation of forces,” challenges the La Paz daily La Razón, “why impede a consulta that will only favor your position in defense of the park?”

It is a question many are asking, and the answer is not simple.

To begin with, as TIPNIS leaders have frequently explained, the official consultation process will be anything but “prior,” since the construction contract and funding agreements for the road have long been executed. The government rationalizes that the ex-post facto consulta will “right two wrongs:” its failure to consult with TIPNIS groups prior to initiating the TIPNIS road, and also prior to cancelling it (by a law promulgated last October, which is still in force). Though not a legally valid position, it’s arguably a practical approach to moving forward—but only if participants have faith in the process, which is far from the case in this situation.

TIPNIS leaders have voiced concerns that ambiguities in the law could allow outside communities to decide the fate of TIPNIS residents—especially if the consulta is conducted by individual vote, given the indigenous territory’s limited population. However, Montaño insists that the process will be limited to the 63 communities of Mojeño-Trinitario, Chimán, and Yuracaré peoples who inhabit the TIPNIS, with decisions to be made collectively by each community according to its traditions and customs. Communities populated by these three ethnic groups that are located outside the indigenous territory but inside the park (within the so-called Polygon 7 “red line”) will be included, but not the cocalero communities of Quechua/Aymara settlers—a much larger group of 63 sindicatos, with which the lowlands indigenous communities of Polygon 7 are largely assimilated.

While many argue that lowlands indigenous groups who are not part of the collective territorial land title have no constitutional right to consultation, as a practical and political matter these communities—who are affiliated with the dissident Subcentral CONISUR, sponsor of the pro-road counter-march that spawned the consultation law—cannot be excluded. In any case, by the numbers, this organizational plan should still favor the anti-road forces.

CONISUR-affiliated and -leaning communities shown with arrows. Source: SERNAPAccording to a recent survey by anthropologist Xavier Albó, the TIPNIS and Sécure Subcentrals jointly represent 51 communities, most of which are believed to oppose the road. Only 14 communities are affiliated with CONISUR, including three in Polygon 7 (down from nine in 2009, presumably due to assimilation). While the ambiguous identity of some of these communities may present definitional problems for the consulta, and even taking into account that some TIPNIS and Sécure communities (according to Albó) have been “co-opted” by CONISUR, by all appearances the CONISUR-affiliated and -leaning communities are a minority.

CONISUR-affiliated and -leaning communities shown with arrows. Source: SERNAPAccording to a recent survey by anthropologist Xavier Albó, the TIPNIS and Sécure Subcentrals jointly represent 51 communities, most of which are believed to oppose the road. Only 14 communities are affiliated with CONISUR, including three in Polygon 7 (down from nine in 2009, presumably due to assimilation). While the ambiguous identity of some of these communities may present definitional problems for the consulta, and even taking into account that some TIPNIS and Sécure communities (according to Albó) have been “co-opted” by CONISUR, by all appearances the CONISUR-affiliated and -leaning communities are a minority.

But even if the community count and decision-making process works in their favor, TIPNIS leaders and other critics are skeptical that the consultation will be carried out in “good faith” and without bias. Pablo Villegas of the respected non-profit CEDIB notes that the two key government ministries charged with implementing the consulta have a conflict of interest—the Ministry of Public Works having executed the construction contract for the road, and the Ministry of Environment having approved the environmental licenses for the two road segments adjoining the park that are already underway.

Also, as Gonzalo Colque of Fundación Tierra points out, the framing of the questions that will be the subject of the consulta seems designed to achieve a pro-road result. Communities will be asked whether the TIPNIS should remain “untouchable,” or should permit development activities by its indigenous owners along with construction of the highway—a false dichotomy which extends the government’s strategy of denying indigenous groups the right to utilize and sustainably manage the park’s natural resources, if the road is rejected. The option of considering alternative routes to the proposed highway through the reserve, which many communities have indicated they would support, is not addressed.

The outcome of the consulta, as described by Gabriela Montaño, will be a series of consensual agreements between the government and the communities—a result that seems highly susceptible to manipulation. TIPNIS leaders have expressed concerns that the government will be able to sway votes with promises of schools, health clinics, and cell phone services that communities should be demanding by right, not in exchange for supporting a highway.

Confusion over the binding nature of the consulta has added to the level of distrust. As Lorenzo Soliz of the non-profit CIPCA comments, if the pro-road option wins, the consulta can be regarded as binding, as the law appears to suggest. If not, it can be treated as advisory, and the government can formulate supplementary participatory initiatives, such as the oft-proposed referendum in the Beni and Cochabamba departments, to evidence support for the opposite position.

Far from resolving the TIPNIS conflict, many believe that the consulta will heighten tensions between indigenous and peasant sectors, especially migrant settlers, and between lowland indigenous factions. Whatever the outcome, editorializes the daily Pagina Siete, one frustrated impoverished group will be victorious and the other defeated—a recipe for continued conflict and potential violence.

While the TIPNIS Subcentral and the lowlands indigenous federation CIDOB have not yet taken an official position TIPNIS Subcentral President Fernando Vargas. Credit: Fundación Tierra. on the consulta, they have called for another cross-country march with allied sectors, in broad defense of indigenous, environmental, and human rights. The march’s timing seems likely to coincide with the schedule of the consultation process, which must be completed within 120 days of the law’s enactment. It’s unclear how indigenous TIPNIS residents can participate in both activities at once, even if they wanted to.

TIPNIS Subcentral President Fernando Vargas. Credit: Fundación Tierra. on the consulta, they have called for another cross-country march with allied sectors, in broad defense of indigenous, environmental, and human rights. The march’s timing seems likely to coincide with the schedule of the consultation process, which must be completed within 120 days of the law’s enactment. It’s unclear how indigenous TIPNIS residents can participate in both activities at once, even if they wanted to.

This week, the Bolivian Workers Central (COB), which led two general strikes in support of the original lowlands indigenous march in defense of the TIPNIS last fall, declared that it will not join the new mobilization, which it perceives as fostering confrontation. The COB has encouraged dialogue, and has offered to mediate the conflict. Its new leadership is reportedly more sympathetic to the government.

Meanwhile, Bolivia’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), which is responsible for accompanying and monitoring the consulta, has announced that it lacks the funds to proceed with the process, although the law requires the government to provide the necessary resources. This could provide a welcome respite, as Bolivia struggles with the challenge of “letting the people decide” the TIPNIS conflict.

Read more on the TIPNIS conflict on Emily Achtenberg’s blog, Rebel Currents. See also, the January/February 2011 NACLA Report, “Golpistas! Coups and Democracy in the 21st Century;” the September/October 2010 NACLA Report, “After Recognition: Indigenous Peoples Confront Capitalism;” or the September/October 2009 NACLA Report, “Political Environments: Development, Dissent, and the New Extraction.” Or subscribe to NACLA.