Last Sunday federal police brutally repressed lowland indigenous marchers protesting the TIPNIS highway. The move has sparked widespread public outrage in Bolivia, while the response from the government of President Evo Moralesincluding the sudden resignation of Minister of Interior Sacha Llorenti on Tuesday eveningraises more questions than answers.

On Sunday afternoon, 500 federal police using tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons launched a surprise raid on the protesters’ camp near Yucumo, in the department of Beni.  Police raid on TIPNIS protesters. Credit: Erbol.Just hours earlier, the protesters had received an invitation from the government to send a delegation to La Paz to resume negotiations, which they were about to consider in a community-wide meeting.

Police raid on TIPNIS protesters. Credit: Erbol.Just hours earlier, the protesters had received an invitation from the government to send a delegation to La Paz to resume negotiations, which they were about to consider in a community-wide meeting.

According to still unconfirmed reports, the raid resulted in one death (a baby), 45 wounded, and at least 37 unaccounted for, including 7 children. In the confusion, many protesters fled into the woods and children were separated from their families. The police also broke up a nearby road blockade maintained by several hundred “colonists” (highland indigenous farmers), which had been impeding the passage of the marchwith the government’s tacit supportfor several weeks.

The raid came the day after Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca, who had arrived at the march in an effort to mediate the impasse with the colonists, was forced by a group of indigenous women to act as a “human shield,” leading the protest past a police barricade positioned ahead of the roadblock. Later released unharmed, Choquehuanca said that he wanted to continue discussions with the protesters. However, the government officially labeled this incident a “kidnapping.”

Indigenous women march with David Choquehuanca. Credit: La Razón.On Monday morning, government officials cited this episode as a rationale for the police action. According to press secretary Iván Canelas, the march had become a “focus of violence.” Minister of Interior Sacha Llorenti maintained that police had been threatened by marchers with bows and arrows, and that the intervention was necessary to save the protestors from a confrontation with the colonists.

Indigenous women march with David Choquehuanca. Credit: La Razón.On Monday morning, government officials cited this episode as a rationale for the police action. According to press secretary Iván Canelas, the march had become a “focus of violence.” Minister of Interior Sacha Llorenti maintained that police had been threatened by marchers with bows and arrows, and that the intervention was necessary to save the protestors from a confrontation with the colonists.

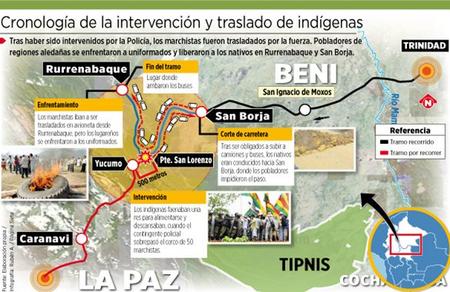

But as TV footage showed indigenous men and women being beaten, gagged with adhesive tape, and dragged on their knees to waiting vehicles, protests against the police repression mounted and spread to regions throughout the country. In Beni, indigenous supporters blocked buses of detained marchers from arriving in San Borja, forcing them to detour to Rurrenabaque, where another group of protestors liberated many of the apparent prisoners before they could be boarded onto a plane to an unknown destination.

An indefinite civic strike has closed businesses and government offices throughout the Beni department, with six road blockades around the capital. More than 5,000 marched and held vigils in La Paz on Monday, while hunger strikes began in Santa Cruz. Also on Monday, the Minister of Defense resigned in protest, followed the next day by two sub-cabinet level officials.

In a Monday evening press conference, President Evo Morales lamented and repudiated the violence and abuses committed by policewhile suggesting that the outcome could have been worse, had the marchers been permitted to confront the colonists. He denied ordering the police action and called for a full investigation by a high-level commission of human rights monitors, international organizations, and Bolivia’s independent Ombudsman.  Chronology of Beni protesters’ interventions to rescue detained marchers. Credit: Página Siete.

Chronology of Beni protesters’ interventions to rescue detained marchers. Credit: Página Siete.

Morales also announced that he would “suspend construction” of the controversial road through the TIPNIS park and indigenous territory, pending the outcome of a national debate and a referendum to be held in the Cochabamba and Beni departments. He emphasized the road’s importance for Bolivia’s economic integration, its basis in past legal norms, and its support by 12 (out of 64) indigenous communities within the TIPNIS.

On Tuesday evening, after a public controversy involving a just-resigned vice minister, police officials, and Sacha Llorenti over responsibility for ordering the raid, Llorenti stepped downwithout any admission of wrong-doing. Llorenti’s claim that the intervention was authorized by a legal order was also denied by the Attorney General.

As the TIPNIS protesters and their growing legions of supporters prepare for a national civic strike on Wednesday, led by the COB (Bolivian Workers Central), the government’s actions leave many questions unanswered. Who was responsible for ordering the police raid? How will the “intellectual authors” of the violent intervention (and not just a few “rogue” police) be held accountable?

Regarding the TIPNIS road, exactly what actions have been suspended? The controversial segment through the TIPNIS park is not yet under construction.  La Paz mobilization to support TIPNIS marchers, September 26. Credit: La Razón.There’s no evidence that work has been halted on adjoining sections that are currently being built, or that the government plans to cancel its construction contract with Brazilian company OAS.

La Paz mobilization to support TIPNIS marchers, September 26. Credit: La Razón.There’s no evidence that work has been halted on adjoining sections that are currently being built, or that the government plans to cancel its construction contract with Brazilian company OAS.

And while the proposal for a national debate and departmental referendum may sound like participatory democracy, how does it satisfy the government’s legal obligation to seek the “free, prior, and informed consent” specifically of indigenous groups residing within the affected territory? This is a requirement of international accords to which Bolivia subscribes, as well as the Bolivian constitution. It’s not yet clear if the Morales government recognizes that the decision on the TIPNIS road can’t just be subject to a popular vote (which the government would likely win within the two departments), but must respect the rights of indigenous minorities within the plurinational state.

In the meantime, conservative opponents of the Morales government are seizing the opportunity to exploit the current crisis in every possible way. It’s a critical and risky moment for Bolivia’s “process of change.”

Read more on the TIPNIS conflict on Emily Achtenberg’s blog, Rebel Currents. See also, the January/February 2011 NACLA Report, “Golpistas! Coups and Democracy in the 21st Century;” the September/October 2010 NACLA Report, “After Recognition: Indigenous Peoples Confront Capitalism;” or the September/October 2009 NACLA Report, “Political Environments: Development, Dissent, and the New Extraction.” Or subscribe to NACLA.