Bolivians paid tribute this week to Domitila Barrios de Chungara, long-time social activist, union leader, feminist, revolutionary, and national heroine who died March 13 in Cochabamba at age 74. She is best known as the miner’s wife who led a hunger strike in 1978 that brought down the dictatorship of General Hugo Bánzer, paving the way for the return of Bolivian democracy.

Credit: Ben Achtenberg, refugemediaproject.org“The democracy that we have been living since 1982 is thanks to Domitila,” said Filemón Escobar, an original founder and ex-Senator of the Movement towards Socialism (MAS) party. President Evo Morales declared three days of national mourning and awarded Domitila the posthumous Condor of the Andes honor, the highest distinction the state can confer on a Bolivian citizen.

Credit: Ben Achtenberg, refugemediaproject.org“The democracy that we have been living since 1982 is thanks to Domitila,” said Filemón Escobar, an original founder and ex-Senator of the Movement towards Socialism (MAS) party. President Evo Morales declared three days of national mourning and awarded Domitila the posthumous Condor of the Andes honor, the highest distinction the state can confer on a Bolivian citizen.

Domitila’s life is a testimony to Bolivia’s tragic history of exploitation, repression, colonialism, and patriarchalism, but also to the power of ordinary people to demand and effect change. Born in 1937 in Potosí, then the largest tin-producing region of Bolivia, she was the daughter and wife of a miner. Losing her mother at age 10, she raised five younger sisters and then seven surviving children of her own under conditions of extreme deprivation and poverty.

Union of Miners Wives. Familia Chungara/ Los TiemposIn the 1960s, Domitila became an outspoken leader of the Union of Miners Wives, organizing mining families for improved conditions and services and struggling against the repressive CIA-backed Barrientos regime. She survived the brutal 1967 San Juan massacre, where soldiers opened fire on striking miners and their wives and children, in part to head off a rumored alliance with Che’s guerrillas fighting in the Santa Cruz mountains. In the ensuing repression, she was jailed and tortured, suffering a stillbirth and internal injuries which caused chronic health problems throughout her life.

Union of Miners Wives. Familia Chungara/ Los TiemposIn the 1960s, Domitila became an outspoken leader of the Union of Miners Wives, organizing mining families for improved conditions and services and struggling against the repressive CIA-backed Barrientos regime. She survived the brutal 1967 San Juan massacre, where soldiers opened fire on striking miners and their wives and children, in part to head off a rumored alliance with Che’s guerrillas fighting in the Santa Cruz mountains. In the ensuing repression, she was jailed and tortured, suffering a stillbirth and internal injuries which caused chronic health problems throughout her life. Hunger strike, 1978. Credit: Opinión.

Hunger strike, 1978. Credit: Opinión.

In 1978, the hunger strike launched by Domitila and four other miners’ wives against the Bánzer government (another US-backed dictatorship) captured the spirit of an entire nation. The strikers demanded freedom for imprisoned mineworkers, amnesty for exiled union leaders, demilitarization of the mines, and general elections. Thousands of Bolivians joined the strike and, on the 23rd day, the government conceded to the protesters’ demands. (Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano recounts the episode dramatically in Memories of Fire, his chronicle of Latin American popular history.)

Domitila gained international recognition at the International Women’s Forum in Mexico in 1975, giving voice to the Bolivian mineworkers’ struggle and the critical role of women activists. Let Me Speak, her autobiographical account of everyday struggles as a mother, worker, union leader, and political activist, was published in 1978 and has been translated into dozens of languages. In 2005, she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize on a slate of “1000 women for peace.”

Credit: Los Tiempos.Domitila was in exile for several years, returning to Bolivia in 1982—just ahead of the massive neoliberal structural readjustment that closed the state-owned mines where she spent her formative years, and threw 30,000 miners out of work. In her last years, she focused her energies on developing a Mobile School for Political Training, bringing political consciousness and popular history to new generations in Cochabamba’s most impoverished barrios—populated largely by the families of ex-miners—and to communities throughout Bolivia.

Credit: Los Tiempos.Domitila was in exile for several years, returning to Bolivia in 1982—just ahead of the massive neoliberal structural readjustment that closed the state-owned mines where she spent her formative years, and threw 30,000 miners out of work. In her last years, she focused her energies on developing a Mobile School for Political Training, bringing political consciousness and popular history to new generations in Cochabamba’s most impoverished barrios—populated largely by the families of ex-miners—and to communities throughout Bolivia.

I was privileged to meet Domitila on two visits to Bolivia, in 2006 and 2008. She was a great story-teller, captivating us with anecdotes of modern Bolivian history from her unique perspective as a participant in the events, and conveying immense dignity, compassion, and determination along with her insights. Three hours later and only up to 1985, we almost missed our flight to La Paz.

As the Cochabamba daily Los Tiempos editorializes, Domitila was controversial in death as in life. Her independence and critical spirit caused discomfort for some, as much as it offered inspiration to others. She died in poverty with a reduced pension and no medical insurance, aided by the solidarity of friends and comrades including some ex-MAS government officials.

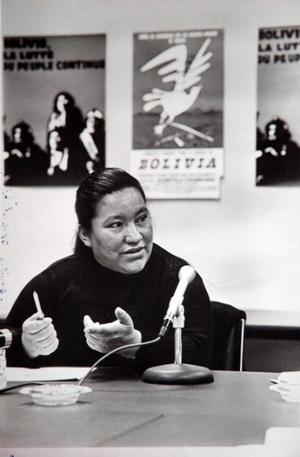

I was reminded of how, on our official visit to the legislative palace in 2006 to hold a press conference demanding Bolivia’s withdrawal from the School of the Americas, Domitila was initially refused entry because she had forgotten her identification. SOA press conference, 2006. Credit: Ben Achtenberg. Unrecognized by the palace guards, she appeared to them as just another stocky peasant woman without a valid reason to be in the halls of political power.

SOA press conference, 2006. Credit: Ben Achtenberg. Unrecognized by the palace guards, she appeared to them as just another stocky peasant woman without a valid reason to be in the halls of political power.

Domitila’s life encapsulates all the possibilities and challenges of Bolivia, demonstrating both the efficacy of collective struggle and the continuing need to confront exploitation, inequality, and entrenched power relationships in government, the workplace, the home, and even within organized popular movements. Her experience reminds us how ordinary people can change the course of history, a legacy for activists throughout the world.

Read more Bolivian activism, including the TIPNIS conflict, on Emily Achtenberg’s blog, Rebel Currents. See also, the January/February 2011 NACLA Report, “Golpistas! Coups and Democracy in the 21st Century;” the September/October 2010 NACLA Report, “After Recognition: Indigenous Peoples Confront Capitalism;” or the September/October 2009 NACLA Report, “Political Environments: Development, Dissent, and the New Extraction.” Or subscribe to NACLA.