President Reagan’s justification for siphoning money out of the collective pool and into the pockets of the wealthy remains in vogue today. If the government pursues tax cuts and subsidies for the rich, so the pitch goes, everyone will benefit. The wealth at the top will eventually “trickle-down.”

Yet in practice, the past two decades have seen wealth accumulate with spectacularly unjust concentrations: more people are poor, and the rich are incredibly rich. This is true within the United States and when comparing the U.S. to other countries.

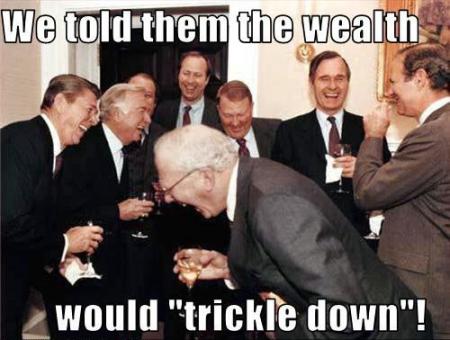

When Reagan advocated tax breaks for corporations, the evisceration of public welfare programs, the expansion of the military, and tax breaks for the wealthy, his critics mocked his policies for the obvious inadequacy of anything that might “trickle-down.” Today, however, in Congress at least, the premise behind “trickle-down” seems to be a point of pride. President Ronald Reagan, Walter Cronkite, Jim Brady, David Gergen, Ed Meese, George Bush, Jim Baker and Bud Benjamin laughing together at the White House. This is an unidentified internet artist’s aptly embellished version (thanks due to Steve Fradkin for the image.)

President Ronald Reagan, Walter Cronkite, Jim Brady, David Gergen, Ed Meese, George Bush, Jim Baker and Bud Benjamin laughing together at the White House. This is an unidentified internet artist’s aptly embellished version (thanks due to Steve Fradkin for the image.)

Despite ample evidence of the human costs of this approach, proponents of “trickle-down” economics (who dominate both political parties) embrace the model with a particular ferocity. The idea of drawing back on subsidies or tax-breaks for wealth are not even on the table until the last remaining public programs are disposed of on the chopping block. The public is left to trust that livable foundations will grow again, once the wealth trickles back down.

Right now the nation’s (elected) government representatives are holding a shoot out over a manufactured crisis, even while the majority of people in the U.S. have been living in financial crisis for a while. Two decades of “trickle-down” economics contributed to our current unsustainable predicament. And yet, whether out of cynicism or an extremist faith, the argument among government officials seems to be only over the terms of “trickle-down’s” consolidation.

This economic approach is perhaps even more evident once you look further “down.” U.S. economic policy in relation to the people and countries of Latin America is coordinated through the Office of the United States Trade Representative. The current policy focus of this office is to promote ratification of three so-called “free” trade agreements involving Colombia, Panama and South Korea. Office of the United States Trade Representative: based on the name cards, participants included Ron Kirk, John Negroponte, Rep. Charles Rangel, Alan Stoga, and others.

Office of the United States Trade Representative: based on the name cards, participants included Ron Kirk, John Negroponte, Rep. Charles Rangel, Alan Stoga, and others.

There is much to be said about these agreements—and the men negotiating them—and I confess I am still a novice wading through reams of legal discourse. But central to all of them are provisions which stiffen regulations concerning what are termed “intellectual property rights.” These provisions have particular weight in relation to the pharmaceutical industry. Essentially they strengthen U.S. companies’ power to wield drug patent privileges and effectively secure U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturers’ dominance in the market, even if this drives up the cost of essential medicine for people living for example in Peru. Signed in 2006, The United States-Peru Trade Promotion Agreement (PTPA) officially took effect in 2009. Since the signing of the agreement, the volume of US pharmaceuticals exported to the country has skyrocketed as the average tariff barrier for US products dropped from 12 percent to 1 percent. While in 2006 fourteen and a half million dollars worth of US pharmaceuticals were imported into Peru, in 2010 that figure increased more than six fold to more than eighty nine and a half million dollars.

Even so, perhaps in the voracious spirit of “trickle-down”, the American Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association advised the office of the US Trade Representative that Peru should remain on the “Watch List” of countries inadequately protecting intellectual property rights in relation to the legal drug trade conducted with the United States.

Maybe this is related to a growing and vocal dissent confronting these priorities. People are regularly denied access to necessary medicines because of exorbitant regulations, patent laws and the policing powers which accompany international enforcement of intellectual property claims. In 2009, as Puentes reported, there was popular outrage over the confiscation in Holland of a shipment of generic hypertension drugs en route to Brazil from India, laying bare many of these concerns.

Today Ollanta Humala will be sworn in as President of Peru. In his last bid for the Presidency Humala opposed a free trade agreement with the United States. This position provoked much public anxiety in the industrial world over whether now he would follow “Chavez or Lula”. What will happen once Humala assumes the presidency is unclear, but likely he will follow neither example. Earlier this month Humala visited Washington and reaffirmed Peruvian commitment to honor his predecessor’s trade agreements with the United States. And just yesterday Wall Street expressed relief at his appointment of an apparent “dream team” of economists “adored” by financial capital.

It is hard to disentangle much of the hype at the moment, but I hold out hope that Humala’s sometime commitment to challenge the dictates of “free trade” may come to fruition. It is yet to be seen what the new Presidency in Peru will try to accomplish.

As for the Reagan & Co. photo, I would be laughing too. The real crimes are in plain sight.