Readers of NACLA are already familiar with the truth about the so-called War on Drugs. We know by now that it is a sinister matrix of U.S. imperialism, in which a critical mass of guns, debt, racism, poverty, and violence against women is channeled through structural adjustment, immigration, penal and free trade policies, all of which churn together in the blood and drug delta of finance capital. The writing is on the wall and the end game has arrived. Legalization is no longer a bad word but a reality in some U.S. states and the central demand of a national mass movement in Mexico. The stakes are higher than everthe moral argument for the drug war was lost long ago, yet as the saying goes, the dying bull kicks the hardest. Escalated drug war policy continues to wreak havoc throughout the world, and in Mexico the cost long ago became unbearable. It has been almost 20 years since the Zapatistas said Ya Basta!, and the question for us is no longer why the old order must end, but how a new world can begin.

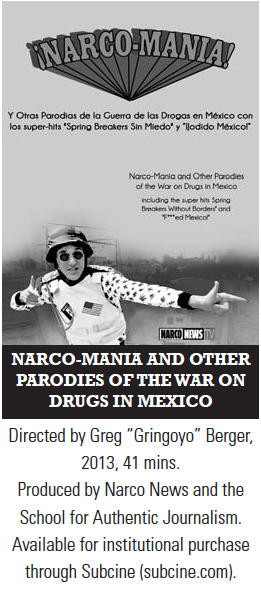

From the front lines of globalization comes a paradoxical proposition: If our era of tragedy is drowning in tears, perhaps we can laugh our way to freedom. Narco-Mania and Other Parodies of the War on Drugs in Mexico, directed by Greg Gringoyo Berger and produced by Narco News and the School for Authentic Journalism, is here to seal the fate of the drug war and to move us forward into the struggle for a new world, armed with comedy.

Gringoyo has been living in Mexico since 1998. He had the beginnings of a successful professional career and worked for Telesur. His serious movies were exhibited at the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art, El Museo del Barrio in New York, and in the Zócalo in downtown Mexico City. But Berger, to his great credit, was not content to stay within this industry paradigm. Today, in addition to raising his son and teaching at the Narco News School of Authentic Journalism, he teaches cinema at the Autonomous University of Morelos, including the only queer film class in Mexico. He calls himself a recovering documentary filmmaker.

For the last decade, Gringoyo has devoted himself to making funny short movies about U.S. imperialism and, with this most recent release, the war on drugs in Mexico. If there is nothing funny about the drug war, then we should bear in mind the words of Alexander Herzen: Laughter is no matter for joking. What Gringoyo offers us here is not just a laugh but a tool to build and strengthen a movement. As the former rebel-prankster mayor of Caracas Juan Barreto once told me, If its not funny, its not serious. In this hilarious collection of bilingual video shorts, Gringoyo dissects the drug war, the interests behind perpetuating it, and the movements committed to ending it.

Seriously? Yes! And no. In the title film Narco-Mania, a Beatles-themed investigation headed by correspondent Gringo-Starr uncovers a secret U.S. plot to break up the Sinaloa cartel by hooking up Yoko Ono with its leader Joaquín Guzmán, all set to the audio-visual theme of A Hard Days Night. Without a doubt, a bizarre and ludicrous premise, and yet, as the video concludes, these made up stories are no more absurd than the drug war itself.

Between laughs, Gringoyos videos offer poignant analyses and perspectives from dedicated organizers and political analysts, complete with official statistics and interviews with people on the street. The effect can be unsettling: How can we laugh in the midst of such bloodshed? In a recent interview on National Public Radio, Gringoyo commented: Making jokes about extremely tragic subjects is something that people are experts at here in Mexico. . . . When you make jokes about the most tragic of subjects you can actually engage in some very profound communication. Whatever the political correctness police may think, one thing is sure: Greg has earned the trust of the victims of the drug war, who are not only the subjects of his films but collaborators in producing them.

Investigative journalist Marta Molina writes, Gringoyo is the only person who can do this. He is the only one who can put humor into this in a creative way. Interviewed by Leah Hennessey, Molina, who works constantly with victims of the drug war . . . says that many of them who have met Gringoyo through his projects feel a great degree of trust in him. Maria Herrera, a 68-year-old woman, who has lost four children to the drug war, asks for Gringoyo every time she sees Molina.

These films are both entertaining and informative to an audience beyond the usual choir of activists, and they are useful to and appreciated by the people and movements about whom they are made. In any case, the inclusion of two non-comedic movies on this DVD (a communiqué from movement leader Javier Sicilia and a stirring piece about the fearlessness of a drug war victim, titled This Is Maria remind us that the filmmaker understands the gravity of the issues.

These videos are controversial on many levels: If they make it through the politically correct gauntlet, they will also have to contend with the gatekeepers of journalism, and then, finally, the copyright cartels. On the politically correct front, some will wonder if its appropriate for a gringo to be making these comedic films. They will be interested to learn that, as Hennessey says, followers of Gringoyo often comment on his website that Berger cannot possibly be a gringo and say that they have listened carefully, over and over, to his speeches and come to the conclusion he has a distinctly Mexican accent, which he has artfully disguised as Californian.

The gatekeepers of journalism are having a hard time lately, as the public increasingly turns to blogs, YouTube, and other free online media for news and analysis. Without digressing into how much they deserve to lose their audience (present company excluded, of course),we note that that Greg is leading the charge against the barricades of so-called professional journalism.

Narco News director Al Giordano explained to interviewer Alex Elgee: Greg has really figured out that instead of spending six months on a film project which few people will see, you can spend a number of weeks on a smaller made-for-Internet piece and more people will see it. You can make it viral and get your message out to so many more people. Greg is kind of pioneer in this type of news.

Are funny viral videos on YouTube really a form of journalism? In response, we might ask what is at stake in the questionis it the fate of journalism itself or the careers of those who have a stake in an industry with a declining market share? Gringoyo is straightforward about his work: It tells a story, the facts are true and its based on real issues. [Elgee] . . . If you actually go out and do something with people, in a group, something creative, something youre not expecting, and something surprising, something that you feel passionate about because of the movie youve seen, that movie is successful. [Hennessey] . . . As we see traditional media die, this type of authentic journalism is the future, and may just take over. [Elgee]

As if this heresy werent enough, Gringoyo takes it a step further going up against the copyright cartels. Not only does he develop professional relationships with the movie pirateers who work the streets of Mexico, encouraging them to copy his movies, he also encourages his fans to avoid paying the cost of the films and to watch them free on the Internet! His early movies always concluded with the slogan Say Yes to Piracy!.

Gringoyos funny fearlessness on all of these fronts has earned him more respect from social movements than many professional journalists can boast. The renowned Bolivian agitator and organizer Oscar Olivera (who collaborated with Gringoyo on one of his earlier films, The Gringomobile Diaries) said that during his time working in Bolivia, Gringoyo was very sympathetic to our people and was liked by everyone, and that he is a big thinker, always making ambitious plans. (Elgee) As Hennessey captures well in her review of his work, Gringoyos hilarious and ironic statements do not take away from the images themselves; they provoke closer attention and sensitive inquiry. In particular, Gringoyos use of an atrociously gringo accent, impossibly combined with colloquialisms that only locals would know, cuts across expectations and prejudices, earning him sincere recognition among locals on both sides of the border. Alexander Herzen once wrote, Only equals may laugh. Thus, this decidedly laughable DVD is not only entertaining, informative, and accountable, but a weapon in the long struggle for a revolution in which Americans on all sides of the border can meet as equals.

This self-described gringo recovering documentary filmmaker may seem an unlikely candidate to play a role in revolutionary history, but Gringoyo is earning himself a place in a history of subversion that stretches back to the fools of the medieval courts. Mark Twain considered laughter the one effective weapon of the human race, and Herzen noted, Laughter contains something revolutionary, contending that Voltaires laughter was more destructive than Rousseaus weeping. In the same way, this DVD will very likely do more to smash the myth of the best of all possible drug wars than the most solemn and sober of documentaries.

Gringoyo carries on the noble, daring, and righteous tradition of the clown: He counsels his students that the most effective way to kill a social movement is to make boring media about it, and the way to win is to laugh your ass off. Like Nietzsches Zarathustra, Gringoyo has come down from the mountaintop: And when I saw my devil I found him serious, thorough, profound, and solemn: it was the spirit of gravitythrough him all things fall. Not by wrath does one kill but by laughter. This is how were going to end the war on drugs and defeat imperialism. No joke. Or is it?

Its silly to take comedy seriously, because to do so is to miss the point. Laughter is its own domain. As Mikhail Bakhtin wrote:

[I]t builds its own world versus the official world, its own church versus the official church, its own state versus the official state. . . . Laughter is essentially not an external but an internal form of truth; it cannot be transformed into seriousness without destroying and distorting the very contents of the truth which it unveils. Laughter liberates not only from external censorship but first of all from the great interior censor; it liberates us from the fear that developed in man during thousands of years: fear of the sacred, of prohibitions, of the past, of power. . . . Laughter opened mens eyes on that which is new, on the future. . . . Hell has burst and has poured forth abundance.

So its not serious but we have to take it seriously. Confused? Good. As Bertold Brecht told us, In the contradiction is the hope. The drug war was never so funny and never so close to being over. Its not a coincidence. Laugh your way to freedom.

Quincy Saul is a writer, organizer, and musician living in the occupied territories of the United States. Among other things, he is the co-editor of Maroon the Implacable: The Collected Writings of Russell Maroon Shoatz (PM Press, YEAR), and a co-founder of Ecosocialist Horizons (ecosocialisthorizons.com). More of his writings can be found in Narco News, The Africa Report, Capitalism Nature Socialism, and his blog, Yo No Me Callo: smashthisscreen.blogspot.com.

Read the rest of NACLA’s Spring 2013 issue: “The Climate Debt: Who Profits, Who Pays?”