War is a racket, U.S. Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler once remarked, describing U.S. war profiteering in World War I as a marginally moral enterprise. From the last half of the 20th century and into the 21st, U.S. covert operations and secretive intelligence agencies have invented a new kind of racket, one that covertly guides foreign policy to the benefit of powerful interests. Beyond overt profiteering, covert operations have at times become preferred modes of intervention when wars appeared to be too costly and unpopular to be supported by the general population.

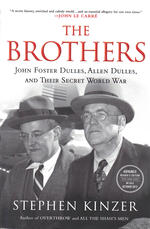

A new book from former New York Times correspondent Stephen Kinzer, The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War, profiles the nexus, frequently covert, that ties together Wall Street law firms, powerful corporations, and U.S. foreign policymakers. The book provides a fascinating look at two individuals who arguably did more than any others to shape U.S. policy abroad and entrench U.S. global dominance: John Foster Dulles and his brother Allen.

John Foster Dullesusually referred to in the book as Fosterand Allen Dulles were secretary of state and director of the CIA, respectively, during a formative period: the hardening and intensification of the Cold War during the Eisenhower administration. This was a period in which the United States launched a wave of covert interventions abroad, engineering coups in Guatemala, Iran, and the Congo, and attempting to destabilize and topple other governments in places as diverse as Indonesia, China, Vietnam, and Cuba. In Kinzers narrative, the Dulles brothers played a large part in guiding this covert aggressiveness.

Kinzer offers an entertaining look at the Dulless personalities throughout: their similarities and differences, their marriages, their (in Allens case) affairs, their friendships, and their escapades. The brothers were born into power. Their grandfather John Watson Foster served briefly as President Benjamin Harrisons secretary of state and helped direct the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. He became, Kinzer writes, a visionary protolobbyist [who] thrived on his ability to shape American foreign policy to the benefit of well paying clients. He was also an early advocate of U.S. foreign intelligence. Grandfather Foster and the boys uncle Robert LansingPresident Woodrow Wilsons secretary of stateproved able mentors, instilling in the boys a Calvinist worldview of good forces in battle with evil.

Among the forces for good were U.S. business interests and captains of industry, who the Dulles brothers would get to know while working for the Wall Street law firm Sullivan and Cromwell. It was there that they began the practice of shaping events abroad to benefit U.S. corporations. Allen was accused, for example, of fixing Colombias 1930 presidential election in favor of a candidate who would protect a clients oil interests. Foster excelled in creating cartels, and would help create the highly lucrative market of international finance on a grand scale, arranging loans to Latin American countries from Brown Brothers, Goldman Sachs, and other large banks. Kinzer writes that in post-WWI Germany, for example, the idea for these loans often came not from needy borrowers, but from Foster and his agents, who scoured Europe and especially Germany for places they could profitably place their money. He notes that one such hamlet was persuaded to borrow $3 million, even though it needed only about $125,000. The brothers Sullivan and Cromwell connectionsas well as their personal business ties to companies such as the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and United Fruitwould later emerge as factors behind their zeal to bring down leaders like Mohammad Mossadegh and Jacobo Arbenz in Iran and Guatemala, respectively. Such practices were wholly compatible with the Wilsonian liberal internationalism that, Kinzer writes, was aimed at forcing other countries to accept trade agreements favorable to American interests. At its core was the reassuring belief that whatever benefited American business would ultimately benefit everyone.

The Calvinist good versus evil outlook would help guide both brothers actions. As top U.S. diplomat, Foster would eschew diplomacy with Communist countries, leading to lost opportunities for disarmament and peace with the USSR, China, and Vietnam. Once the Cold War began, there was no room for neutralism in the Dulless eyes either: non-aligned countries were no better than pro-Soviet. This would help lead to such travesties of justice as the overthrow and brutal murder of Patrice Lumumba in the Congo and the slaughter of over a half million Indonesians as the U.S. government attempted firstin an Allen-led bungled operationand then successfully (under Lyndon Johnson) to topple President Sukarno in Indonesia.

Lumumba and Sukarno were just two of the six monsters that Foster and Allen set out to destroy, and these efforts make up roughly half of the narrative. Along with the U.S.-engineered coups in Iran and Guatemala, the downfalls of Lumumba and Sukarno were the brothers successes. The operations against Ho Chi Minh in Vietnam and Fidel Castro in Cuba would be another story, but each campaign would leave a lasting, detrimental legacy for the countries targeted, for the United States, and for the world.

The Brothers is an important work for revealing how business interestssometimes personalhave shaped U.S. foreign policy. Not only did Foster and Allen hold United Fruit stock as they launched the coup against the Arbenz government, but the assistant secretary of state for inter-American affairs at the time did also, as well as the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. National Security Advisor Robert Cutler was a former board member. Kinzer points out that it was no accident that the places the Dulleses targeted were often those where Sullivan and Cromwell clients had interests: Iran, Guatemala and Cuba, among others.

Another key point that Kinzer makes is that Fosteras an early and powerful proponent of war with Vietnammay be more responsible than any other U.S. citizen for the U.S.-Vietnam conflict that would drag on for a decade and a half after his death. Fosters stubbornness led to the scuttling of an opportunity for peace in 1954, even as the French government conceded that there should be an independent Vietnam. Foster determined that the United States should rush in where France no longer wanted to tread; the results ultimately would be 58,000 U.S. and millions of Vietnamese, Laotian and Cambodian deathsand an independent, Communist Vietnam.

As head of the CIA, Allen initiated what would be some of the agencys most reprehensible practices, including its support for former Nazis and terrorists, torture in secret prisons, and its (sometimes unwitting) dosing with LSD of prisoners, mental patients, prostitutes, and others in mind-control experiments. Allen left a legacy of tremendous failures, peppered with a few triumphs, but Kinzer does not detail the blunders as thoroughly as Tim Weiner did in his CIA history, Legacy of Ashes. Allen Dulless attempted overthrow of Sukarno led to the killings of thousands of civilians, and the rise of the Indonesian Communist party. His covert war on China from northern Burmamentioned, but not in great detailhad the effect of further destabilizing a region that remains one of the worlds main sources of opium production. It was also Allens CIA that carelessly shared information that was immediately leaked to the USSRoften through drinking sessions involving counterintelligence chief James Angleton and Soviet spy Kim Philby. The Bay of Pigs was Allens last, catastrophic failure. As Kinzer has pointed out, the brothers also gave little thought to the legacy of such foreign meddling, and their few successes would lead to some of the worst blowback and quagmires that have dragged the United States down in the decades since.

Another important and often-overlooked aspect of U.S. intelligence practices that Kinzer describes in scattered anecdotes and asides concerns the U.S. media. Kinzer notes how Allen wielded enormous influenceand controlover major U.S. media outlets, including the New York Times and Time Magazine. Allen had a number of regulator media collaborators, and could have reporters fired or reassigned with just a phone call. Under Operation Mockingbird his CIA regularly plantedand then created media cycles aroundpropaganda against foreign leaders.

Kinzer humanizes his subjects far too much for The Brothers to be dismissed as a hit job, but he does throw open the closets and pull the skeletons out. One of the more appalling is Fosters dealings with Nazi Germany on behalf of Sullivan and Cromwell clients. Foster, Kinzer relates, was no casual business supporter of Hitlers regime, but instrumental in providing access to capital and resources. This gave Nazi Germany crucial assistance in building its war machine, in part through German nickel producer I.G. Farben. Foster helped [this company] establish a global chemical cartel; it would later make the Zyklon B gas used in the Nazi death camps. Foster also wrote sympathetically of Germany, Italy and Japan in the media, and supported the pro-Nazi America First movement. Allen also had Nazi pals; the book notes that he shielded former second man of the SS Karl Wolff from justice at Nuremberg. Allen met Hitler himself in Berlin in 1933, Kinzer writes, and though gangs of Nazi thugs were beating Jews on German streets while Allen was there [ ] he came home without animus toward Hitler.

Kinzers descriptions of the brothers personalities are a bit repetitive at times (there are numerous iterations of how uptight Foster was, while Allen was a libertine), and readers familiar with some of Kinzers other works such as Bitter Fruit, All the Shahs Men and Overthrow will already know some of the histories laid out here. But bringing the role of the Dulles brothers to the fore sheds light on an important aspect of the history of U.S. foreign intervention too often overlooked: the intersection of the interests of Wall Street finance, powerful corporations, foreign elites, and the U.S. intelligence apparatus. We can only guess how different history may have been if two other individuals had occupied the roles of secretary of state and CIA director during this period, but it seems clear that the Dulles brothers left a profound legacy. Much of itfrom the ongoing blockade against Cuba, to the lasting tragic impact of the Vietnam War, to heightened U.S. insecurity from terrorismremain with us still.

Dan Beeton is International Communications Director at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (www.cepr.net).

Read the rest of NACLA’s Spring 2014 issue: “Mexico: The State Against the Working Class“