Maestra, a documentary film directed by Catherine Murphy, 33 mins., Spanish and English, with English subtitles, 2011, maestrathefilm.org.

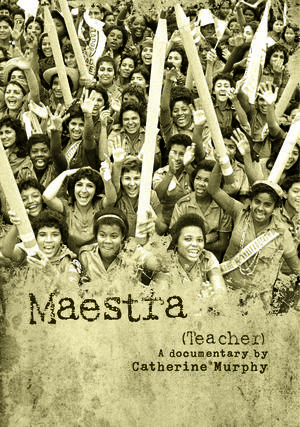

Photo by Liborio Noval (December 22, 1961)The high rate of literacy in Cuba is one of the proud and much touted accomplishments of the Cuban Revolution. Beginning half a century ago, in 1961, the literacy campaign mobilized more than 1 million Cubans as teachers or students. In that same year, 707,000 Cubans learned how to read or write. Maestra tells the story of that inspiring campaign through the memories of the women who served as literacy teachersthe maestras themselves.

Photo by Liborio Noval (December 22, 1961)The high rate of literacy in Cuba is one of the proud and much touted accomplishments of the Cuban Revolution. Beginning half a century ago, in 1961, the literacy campaign mobilized more than 1 million Cubans as teachers or students. In that same year, 707,000 Cubans learned how to read or write. Maestra tells the story of that inspiring campaign through the memories of the women who served as literacy teachersthe maestras themselves.

The filmmaker, Catherine Murphy, lived in Cuba in the 1990s and earned a masters degree at the University of Havana. She is the founder and director of a multimedia project known as the Literacy Project, which focuses on gathering oral histories of volunteer teachers from the literacy campaign. For Maestra, the first documentary to arise from the project, she interviewed more than 50 women and 13 men who were involved in the campaign. Many of them are now in their seventies. She also carried out five years of research in the Cuban national film archives.

Documentary footage shows the energy and enthusiasm of the young women who traveled on trains into the small towns and countryside of Cuba to live among the people and teach them how to read and write. But the challenges they faced were extreme. These women often faced opposition from their families, and many left against their parents wishes. They lived with poor rural families, sleeping in hammocks at night. During the day they would work in the fields alongside the peasants, and in the few hours they had in the evening, they would prepare lessons and conduct classes.

The hardships and poverty they encountered were not always conducive to learning how to read and write. Literacy teacher Diana Balboa recounts the story of a 47-year-old palm tree cutter: His hands were swollen and deformed by such a violent job. He was unable to hold a pencil. I helped him hold the pencil but it fell out of his hands. The man learned to read a bit, but he was never able to write.

In the midst of the literacy campaign, Cuban exiles launched the CIA-supported Bay of Pigs invasion. Although it was discovered and thwarted by the Cuban armed forces, escaped mercenaries combed the countryside, harassing the peasants and their literacy teachers.

In a country where the urban and rural poor had long been denied access to education, literacy was empowerment. For the counter-revolutionaries who wanted to see Cuba return to the status quo, teaching literacy to the poor was an affront to the class order. One teacher recounts the threats to her host family from gunmen who pounded on their door, demanding, Bring out the literacy teachers! But this family, like others across the country, put their lives on the line to protect the teachers. Sadly, they were not always able to escape these threats, and one teacher, Manuel Ascunce, was killed by insurgents.

As the literacy teachers recount, the campaign broke taboos, particularly around gender. Young women in general were subject to the norms of patriarchy. They were not expected to excel at their studies. They were confined to the house, and their futures were limited to what their parents decided for them. Being part of the literacy campaign helped these young women break away from parental constraints. For Norma Guillard, going on the campaign at the age of 15 was an adventure. It was her first time away from home, and it gave her a feeling of freedom and independence.

The film shows how the literacy campaign not only promoted literacy, but also profoundly changed the lives of the maestras themselves. Upon returning from the campaign, they were given scholarships to continue their studies. Guillard signed up immediately. As she recounts, I had become used to moving around and being independent. She eventually trained as a psychologist. Another maestra became a mathematics teacher. These professions were rare for women in the pre-revolutionary order.

In the documentary, we are reminded of the major milestone that Cuba achieved in such a short time. One of the most touching moments is the footage of a man who writes his name on a blackboard in slow, deliberate cursive strokes while a teacher watches from the side. When he finishes he stands in front of his completed name: Pablo Benitez. He has a quiet, proud smile on his face.

The literacy campaign is vitally important to revisit today, given the global challenges of illiteracy. We often think of illiteracy, particularly in Western nations, as a problem eradicated years ago, along with smallpox. But according to UNESCO, about 1 billion peopleor 26% of the worlds adult populationremain non-literate. While developing countries have the highest rates of illiteracy, Western developed nations also have surprisingly high rates. A study carried out in 1998 by the National Institute for Literacy estimated that 47% of adults in Detroit and 36% in New York City were Level 1 readers and writers, meaning that they could perform many tasks involving simple texts and documents, such as signing their names or totaling a bank deposit entry, but could not read well enough to, fill out an application, read a food label, or read a simple story to a child.

Maestra is a compelling and beautifully filmed reconstruction of one of the most significant campaigns in Cubas history. Fifty years on, the film clearly demonstrates the impact that it had on the lives of all those who took part.

Sujatha Fernandes is Assistant Professor of sociology at Queens College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She is the author, most recently, of Close to the Edge: In Search of the Global Hip Hop Generation (Verso, 2011).

Read the rest of NACLA’s September/October 2011 issue: “The Politics of Human Rights.”