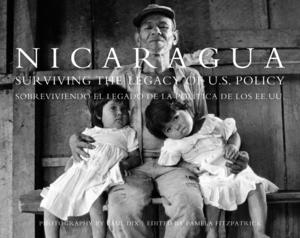

Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy of U.S. Policy, by Paul Dix and Pamela Fitzpatrick, Just Sharing Press, 2011, 220 pp., $39.95, nicaraguaphototestimony.org

A photograph freezes time in two dimensions, but good photographs take the viewer beyond those limits to tell a story, evoke emotions, provoke a response. When Paul Dix lived in Nicaragua in the 1980s, photographing the Contra war for the U.S.-based Witness for Peace, his images often conveyed the pathos of a nation whose revolutionary hopes were turned to ashes by an empire that struck back with brutal efficiency. Dixs imagesmothers at funerals, children without limbs, school-age youth with guns instead of booksfaithfully recorded the effects of war on a small country. You cant view the images without feeling anger or pity or even wonder. Yet his work was more than the conflict pornography weve come to expect from war zones. He also captured the beauty of Nicaraguas rugged countryside and the dignity of its hardy peasants. His collection of images remains a remarkable contribution to understanding, at an intimately personal level, a very painful period in Central Americas political history.

A photograph freezes time in two dimensions, but good photographs take the viewer beyond those limits to tell a story, evoke emotions, provoke a response. When Paul Dix lived in Nicaragua in the 1980s, photographing the Contra war for the U.S.-based Witness for Peace, his images often conveyed the pathos of a nation whose revolutionary hopes were turned to ashes by an empire that struck back with brutal efficiency. Dixs imagesmothers at funerals, children without limbs, school-age youth with guns instead of booksfaithfully recorded the effects of war on a small country. You cant view the images without feeling anger or pity or even wonder. Yet his work was more than the conflict pornography weve come to expect from war zones. He also captured the beauty of Nicaraguas rugged countryside and the dignity of its hardy peasants. His collection of images remains a remarkable contribution to understanding, at an intimately personal level, a very painful period in Central Americas political history.

And now he has done more. Along with Pam Fitzpatrick, an activist who spent those years organizing in the United States to stop the war, Dix has taken some of his more iconic images and allowed us to meet their subjects again, two decades later, in a new book. Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy of U.S. Policy is a monumental contribution that fleshes out those people weve seen in just two dimensions, providing us a unique window onto the country, helping us understand what happened in the 1980s, and what has happened since.

Dix and Fitzpatrick made four trips to Central America over seven years, spending 18 months tracking down people for whom they often didnt even have a name, just a grainy black-and-white image from a fleeting moment years before. Determined detective work eventually led them to almost everyone they were looking for. During these reencounters, Dix would photograph them again, and he and Fitzpatrick would record their stories of what had happened in the intervening years. Sometimes these are powerful narratives of how people overcame both personal obstacles and social strictures. Other times they are stories with no happy ending, of people left irreparably damaged by the violence. There is no common thread to their stories except that they are all victims in one way or another of a war organized and financed by the U.S. government.

The book includes photos of 30 people. Possessing wounds both visible and invisible, they represent Nicaraguas complicated demographics, including those who are still loyal Sandinistas and others who blame the Sandinistas for everything. Still others, consumed with daily survival, long ago grew tired of ascribing political responsibility for their plight. The bilingual text summarizes their stories, and their testimonies appear in the back of the book.

Some of the stories remind us of the feistiness of Nicaraguans, of the revolutionary spirit that has outlasted the political compromises and corruption of the revolutionary party. Dix photographed Jamileth Chavarría in 1987 as she leaned on a cross at the burial of her mother, who was killed by the Contras on the muddy road into the remote jungle outpost of Bocana de Paiwas. A 2002 photograph shows Chavarría at the microphone in a womens radio station in Paiwas. Her accompanying testimony tells of how shes creatively combating the violence against women embodied in Nicaraguan culture as well as in the policies of both government and church.

In her testimony, Chavarría reflects a sentiment common among Nicaraguas poor: Although she knows who killed her mother, she doesnt hate them. Instead, she blames the gringos [who] were the ones that made Nicaragua divide itself. . . . The gringos were behind all of this, and . . . the Contras were also victims of the gringos.

Tomás Alvarado sure looks feisty in a 1990 Dix photo. Hes leading a group of Sandinista activists in an election march from the Honduran border to Managua. Hes in a wheelchair, the result of wounds he suffered in combat against the Contras in 1984, and he exudes enthusiasm for the revolutionary project. In a second image, this one from 2002, hes older and heavier, but playing basketball in his chair. Hes now an activist for the rights of the disabled and talks openly in his testimony of how things have changed since the Sandinistas lost that 1990 election. And hes realistic about his need to fight off the depression that can come easily to war victims like himself.

What is left for you to do, Alvarado says, is turn the chair around and think about how to move forward, first how to get out of bed, then how to leave the house, then how to go out into the street, and then how to work.

Graciela Morales was one of the more difficult subjects to track down. In 1985, Dix captured her holding a flag at a Sandinista rally. No name, just the stirring image of one young woman. Somehow they found Morales in 2007 in Costa Rica, where she practices medicine. In her testimony, she recalls volunteering at age 12 to go to the mountains to teach adults to read and write. Later, she joins the military, and at wars end goes to medical school. She marvels at how the revolution made it possible for her, a girl from a poor family, to become a physician. Had there been no revolution, she said, I would now be a peasant myself, perhaps the mother of five or six little kids, working in the field with my husband.

Other stories in the book are windows into the desperate poverty that still plagues the country. Carmen Picado is first pictured in a 1986 photo, a beautiful 19-year-old woman lying in a hospital bed. Her missing legs are mute testimony to the terror of a Contra mine that killed six and wounded 43 along a road north of the city of Jinotega. She is then shown in 2002 and 2004, one of her walking with crutches along a Matagalpa street with her two children. In describing her situation, Dix and Fitzpatrick note that she survives with no visible means of support. And she confesses that her physical challenges are at times overwhelming. One moment I feel calm, she says, then I feel like something hits me in the heart, and Im overcome with desperation, and I cry and cry and cry.

And then there is Fatima del Socorro Peña, whose 1986 picture of her and her sister Albertina sitting with their great-grandfather graces the books cover. Dix and Fitzpatrick spent weeks hunting for her, and finally found her on an isolated farm near the Costa Rican border. She didnt want to talk much about her life. Asked about what happened to Albertina, she replied simply, My sister died eating dirt.

Not long ago, the Sandinista revolution and counterrevolution were headline news. Yet today, Nicaraguawhich Salman Rushdie in 1987 called a fulcrum of historyhas become much like any other banana republic, plagued by poverty and economic inequality. Yet remembering what happened there in the 1980s is essential, lest amnesia allow history to repeat itself as a nightmare. Books like this are needed to inoculate ourselves against the usurpation of memory by those who wish to replicate such ravages elsewhere.

Dix and Fitzpatrick have done us a favor by presenting this visual history in such a compelling fashion. Theyve also provided additional tools to encourage the books use in college courses or other learning environments. Theres a prologue by renowned Nicaraguan poet Gioconda Belli and a brief history of Nicaragua by Mark Lester. In the forward, Richard Boren, a Witness for Peace activist who was kidnapped by the Contras in 1988, puts some personal perspective on Dixs work by relating how the photographer trekked into the mountains to track down the Contra squad and negotiate for Borens release.

While we in the United States can forget our countrys tragic involvement in Nicaraguas history, the people pictured in this book have no such luxury. They live it every day; they bear signs of it on their bodies and souls. Dix and Fitzpatrick record one Nicaraguan woman who laments the ease with which we remain ignorant.

It is terrible to think that in a country like the United States, for example, the young people who live there dont know anything about what their own country does in other countries, says Coni Pérez. Dixs photo of her, taken in 1988 in the small village of Largatillo, shows Pérez, then a six-year-old girl living in a war zone, swinging upside down from a hammock.

Paul Jeffrey is a U.S.-based photojournalist who lived in Nicaragua during the 1980s. His website is kairosphotos.com.

Read the rest of NACLA’s September/October 2011 issue: “The Politics of Human Rights.”