Latin American cinema is undergoing a renaissance. But while Latin American literature crosses international borders, films are seldom seen outside of their respective countries.

This year, the Mexican film “Como agua para chocolate” (Like Water for Chocolate, 1992), by Alfonso Arau, broke all for- eign-language film records by having 179 subtitled prints screening simultaneously in the

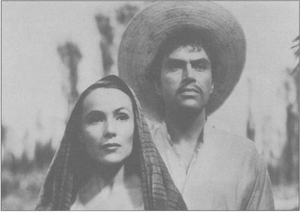

United States, making $8.5 million in its first 16 weeks and placing it fifteenth on Variety’s all-time list of import 8 hits. In U.S. distribu- Dolores Del Rio and Pedro Armend.riz, stars of the Golden Age of Mexican tion last year as well cinema, in “Maria Candelaria” (1943), directed by Emilio FernAndez. were Maria Novaro’s “Danz6n” (1991) and Nicolis Echevarria’s “Cabeza de Vaca” (1991), both also from Mexico.

United States, making $8.5 million in its first 16 weeks and placing it fifteenth on Variety’s all-time list of import 8 hits. In U.S. distribu- Dolores Del Rio and Pedro Armend.riz, stars of the Golden Age of Mexican tion last year as well cinema, in “Maria Candelaria” (1943), directed by Emilio FernAndez. were Maria Novaro’s “Danz6n” (1991) and Nicolis Echevarria’s “Cabeza de Vaca” (1991), both also from Mexico.

Other recent Latin American films that have won international awards and distinctions include: “Caidos del cielo” (Fallen From the Sky), by Peruvian Francisco Lombardi, which won top film at the 1990 Montreal World Film Festival; Argentine Eliseo Subiela’s “El lado oscuro del coraz6n” (The Dark Side of the Heart), which was chosen top film Paul Lenti has been the Latin American film critic and reporter for Variety magazine since 1983. He is the editor of Objects of Desire: Conversations with Luis Bufiuel (Marsilio Publications, 1993). 4 at the 1992 Montreal World Film Festival; “Un lugar en el mundo” (A Place in the World, 1992), an Argentine-Uruguayan coproduc- tion by Adolfo AristarAin, and “Lo que le pas6 a Santiago” (What Happened to Santiago, 1989), by Puerto Rican Jacobo Morales, which were both nominated for Academy Awards for best foreign- language films. (“Lugar” was later withdrawn because of an irregularity.)

Many international critics agree that Latin American cinema is undergoing a renaissance. Yet beyond select festival screenings, most Latin Americans are unable to see their own films. While Latin American literature crosses inter- national borders, films are seldom seen outside of their respective countries. It is nearly impossi- ble to see a Venezue- lan film in Chile, a Chilean film in Colombia, a Col- ombian film in Peru, a Peruvian film in Argentina, or an Argentine film in Mexico. Yet, at the same time, a quick glance at a list of top 10 films at the box office for any given year reveals almost the same list of U.S. films in all Latin American countries.

An institution that is trying to combat this situation is the New Latin American Cinema Founda- tion (Fundaci6n del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano), headquartered at the spacious Finca Santa Bar- bara on the outskirts of Havana. The foundation was established to encourage the production, preser- vation and development of Latin American cinema. It officially opened its doors during the VIII Havana International Film Festival, at a December 1986 ceremony attended by Cuban President Fidel Castro. A press release distributed at the opening stated that the foun- dation was an effort to develop a NACIA REPORT ON THE AMERICASSURVEY / FILM creative body “to stimulate the growth of new Latin American cin- ema, draw attention to works that have not received adequate distrib- ution or recognition in the past, and recover the national and cul- tural values of Latin America.”

At the inaugural ceremony the foundation president, Nobel Prize- winning Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Mirquez, told those gath- ered: “I’m not here to invent a movement or concoct a cultural explosion. That, no mere founda- tion president can do. But rather we wish to stimulate the growth of an already-existing movement and aid in its development. I believe we’ve reached a point where we must give an impulse to this phenomenon that has developed over the past 30 years.”

Latin American a cinema is as old as the medium itself, and its fortunes have always fluctuated Mireya Kulche with changes in both (1974), directed world politics and the political sta- bility of the region. Its first films were produced as far back as 1896, the same year that cinema was first projected in France by the LumiBre brothers. Films spread rapidly throughout Latin America, as the following dates for first public screenings reveal: Argenti- na (July 18, 1896); Brazil (July 28, 1896); Mexico (Aug. 14, 1896); Cuba (Jan. 24, 1897); Venezuela (Jan. 28, 1897); Peru (March 2, 1897); and Bolivia (Nov. 20, 1904). With the advent of sound, both Mexico and Argentina regularly produced quality commercial films that not only pleased domestic audiences but were widely distributed throughout Latin America. Brazil, with a sizable internal market, produced a steady line-up of films in all genres: adventures, melodramas, love stories, musicals, crime dramas, political intrigues, and historical romances. Other countries-including Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Peru and Venezuela–also boasted sporadic early production. The outbreak of World War II reverberated through Latin Ameri- can movie theaters. With European markets closed, Hollywood was encouraged to produce films which wsky (foreground) in the Chilean film, “La tie d by Miguel Littin. appealed to Latin American audiences. The U.S. government punished its war-time enemies and rewarded its allies. It virtually dismantled Argentina’s film industry by withholding film stock to punish that country for its neutral stance, while, through Nelson Rockefeller’s Office for Coordina- tion of Inter-American Affairs, it encouraged heavy investment by U.S. companies in loyal Mexico, resulting in the construction of the Churubusco film studios. The Argentine film industry took years to recover its pre-war production figures, and never fully regained its foreign markets.

As a consequence, Argentina’s Golden Age of Cinema preceded World War II, while Mexico’s cel- luloid glitter came of age during and after the war, seen in the production of film classics such as “Ahi estA el detalle” (There Is the Detail, 1940), starring comedian Mario Moreno “Cantinflas”; Dolores del Rio and Pedro Armenddriz vehicles “Maria Candelaria” (1943) and “Las abandonadas” (1944); and “Dofia Barbara” (1943) and “Maclovia” (1948), with Maria F61ix. The industry regularly churned out singing cowboy films starring Pedro Infante, Tito Guizar and Jorge Negrete, cabaret movies featuring Cuban rhumba dancer Nin6n Sevilla, and melodramas starring heart-throb Arturo de C6rdova and Argentine singer-actress Libertad Lamarque. Appearing on marquees throughout the continent were works by filmmakers Emilio “Indio” Fernindez, Fernando de Fuentes, Roberto Gavald6n, Juan Bustillo Oro and rra prometida” Julio Bracho.

The arrival of television in the 1950s dulled the luster of the Golden Age as viewers began to stay home while TV brought the outside world and big name stars into their living rooms. Television spread rapidly throughout Latin America while its lower production costs attracted local producers, who churned out a continuous slate of game shows, variety shows, soap operas and serials. Reacting to declining box-office figures, Mexico’s film industry simply began to reuse formulas that had worked in the past. The industry buckled under the weight of genre films that replayed themselves again and again in melodra- mas, teen pictures, masked wrestler films and sex comedies.

The so-called New Latin American Cinema has its origins in political events such as the Cuban Revolution and the social unrest of the late 1960s when film began to be used as a medium for the communication of ideas and social change. The French New Wave had washed over world cinema and set people thinking about the pur- pose and aesthetic of cinema beyond mere entertainment. Latin American theorists like Argentines Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, Cubans Julio Garcia Espinosa and TomBs Guti6rrez Alea, Bolivian Jorge Sanjin6s and Brazilian Glauber Rocha developed a new cinema aesthetic. As curator Coco Fusco noted: “In the 1960s and early 1970s, filmmakers offered arguments for a ‘Cinema Novo,’ for ‘Cine de Liberaci6n,’ for ‘Cine Imperfecto,’ for an ‘Aesthetic of Hunger,’ for a ‘Third Cinema’ of decolonization, all terms that have since framed many a debate at home and abroad. Writing about their practice created another forum, another way to integrate cinema into social life. And discussion of their cinema and the issues it raised was, and continues to be, a key element of a much broader project of redefining political and cultural values” (Reviewing Histories: Selections From New Latin American Cinema, Hallwalls, NY, 1987, p. 4).

In an attempt to bolster flagging production and help establish this nascent industry, many governments began to work with film- makers to create coherent film legislation. From 1940 to 1965, Puerto Rico’s Divisi6n de Educaci6n de la Comunidad, for example, produced a number of films dedicated to educating citizens about how to find solutions to community problems. The use of film as an educational tool was later adopted by Cuba and Nicaragua, both of whose governments sent mobile cinema units into the countryside to show films and hold community discussions. An extended network of cinema clubs popped up all over Latin America, usually part of university programs where films were produced and screened. These clubs were responsible for the creation of such groups as Panama’s GECU (Grupo Experimental de Cine Universitario), and the early films of Colombian documentary filmmakers Marta Rodriguez and Jorge Silva.

Cuba understood the power of media, especially cinema. When Preceding Chile’s return to democracy, a new generation of filmmakers echoed the :ountry’s unrest with work like Justiniano’s “Hijos de la guerra fria. ” the Revolution was only three months old, Cuba established the film institute ICAIC (Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cine- matogrificos), which began to regularly produce feature films, documentaries, a weekly newsreel, and a slate of cartoons. Many of its challenging and distinctive films drew critical acclaim at world film festivals, including “La muerte de un bur6crata” (Death of a Bureaucrat, 1966), “Memorias del subdesarrollo” (Memories of Underdevelopment, 1968) and “La tiltima cena” (The Last Supper, 1976) by Tomis Guti6rrez Alea; “De cierta manera” (One Way or Another, 1974) by Sara G6mez; “Retrato de Teresa” (Portrait of Teresa, 1979) by Pastor Vega; “Lucia” (1968) and “Cecilia” (1981) by Humberto Solis; and “El otro Francisco” (The Other Francisco, 1974) by Sergio Giral.

Over the past three decades, Latin American cinema has mirrored the political environment. Although earlier produc- tion had been intermittent, Chile saw a production boom under the leftist government of Salvador Allende. This included “El Chacal de Nahueltoro” (The Jackal of Nahueltoro, 1969) and “La tierra prometida” (The Promised Land, 1974) by Miguel Littin; “Tres tristes tigres” (Three Sad Tigers, 1968) and “La colonia penal” (The Penal Colony, 1971) by Ratll Ruiz; and Patri- cio Guzmin’s award-winning three-part documentary “La Batalla de Chile” (The Battle of Chile, 1973-76), which was completed in exile. This embryonic industry was s crushed by Gen. Pinochet’s September 1973 coup, which forced filmmakers into exile. Preceding Chile’s return to electoral democracy, a new generation of filmmakers echoed the country’s unrest by questioning the dictatorship with works like Gonzalo Justini- ano’s “Hijos de la guerra fria” (Children of the Cold War, 1985), Leonardo Knocking’s “La estaci6n del regreso” (The Season of Our Return, 1987), and “Imagen latente” (Latent Image, 1987) by Pablo Perleman.

Argentina’s return to democracy was also accompanied by a return to filmmaking. Movies provided a vehicle for a national catharsis as Argentina came to grips with the “dirty war” which the military government had waged on its citizenry. These films include: the Academy Award-winning “La historia oficial” (The Official Story, 1985) by Luis Puenzo; “La noche de los lipices” (Night of the Pencils, 6NACIA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS 6 NACIA REPORT ON THE AMERICASSURVEY / FILM 1986) by Hdctor Olivera; “En Retiing Paul Leduc, Jaime Humberto on the nati rada” (Beating a Retreat, 1986) by Hermosillo, Felipe Cazals, Arturo cial cinem Juan Carlos de Sanzo; “Juan, como Ripstein, Alberto Isaac and Alfondictated n si nada hubiera sucedio” (Juan, As so Arau. On the other hand, when domestic s if Nothing Had Ever Happened, President Jos6 L6pez Portillo features. 1987) by Carlos Echeverria; and (1976-82) appointed his sister Marfilmmaker the masterful, poetic film “Sur” garita to head the industry, state create a sw (1987) by Fernando Solanas.

Besides political themes, fell apart, and the final year of the matografia Argentina’s return to democracy administration saw the burning of codifying sparked production of a whole the national film archives. Mexi- new law, ii range of distinctive films, among co’s current renaissance is the a National them: Eliseo Subiela’s “Hombre result of efforts by IMCINE (Insti- an economy mirando al sureste” (Man Facing tuto Mexicano de Cinematografia), ers. As cui Southeast, 1985) and “Las tiltimas which is encouraging young film- further reg imagenes del naufragio” (Last makers who are emerging from the bution and Images of the Ship- wreck, 1989); “La pelicula del rey” (A King and His Movie, 1985) by Carlos Sorin; “Camila” (1984) and “Yo, la peor de todas” (I, the Worst of All, 1991) by Maria Luisa Bem- berg; “Otra historia de amor” (Another Love Story, 1986) by Am6rico Ortiz de Zirate; “La deuda interna” (Ver6nico Cruz/The o From the Chilean film, “Hijos de la guerra fria” (1985), directed by Gonzalo Debt, 1987) by Justiniano. Miguel Pereira; “Boda secreta” (Secret Wedding, country’s two film schools to pro- office tax. 1989) by Alejandro Agresti; and duce cinema that expresses cultural at the end “Kindergarten” (1989) by Jorge identity.

While Mexico did not experitive production methodsmainly mentaries. ence such political extremes, since film cooperatives and universi Venezuela the 1960s its film history can be ties-which have permitted them film body easily traced by sexenios, six-year to delve into new themes. Fomento presidential terms.

Quality cinema Peru’s 1972 Film Promotion 1982, the has either flourished or floundered Law (Ley de Promoci6n Cine- 107 feature depending on whom the president matogrifica), credited with creat- ipated in chooses to govern state production. ing Peru’s film industry, was insti- festivals, When President Luis Echeverria tuted under the left-leaning govern- 100 awar (1970-76) appointed his brother ment of Gen. Juan Velasco Alvara- 1993, afte Rodolfo to head the Banco Cine- do. The cinema law set up manda- tightening matogrdfico, a singular effort was tory screen time for domestic governme made to consolidate all sectors of films. One week of exhibition time annual bud the film industry. As a result, many had to be set aside for Peruvian $6.8 milli new filmmakers emerged, includ- films within an 18-month period raised front onal circuit of commer- as. In addition, the law mandatory screening of shorts to accompany all Since 1986, Peruvian s have been working to ‘eeping national film law Ley General de la Cine- Peruana). In addition to former measures, the f passed, would establish Film Council and create iic fund to aid filmmak- rrently outlined, the law ulates promotion, distri- exhibition. It also estab- lishes norms for pro- duction and coproduc- tion, laboratory quotas and standards, video distribution, preferen- tial exhibition quotas for domestic produc- tions, and regulations covering TV exhibition of films and conserva- tion of domestic films. In 1978, Colombia’s Ministry of Communi- cations established the film institute FOCINE (Compaiiia de Fomento Cinematogrifico) to produce and promote national cinema, fund- ed by an 8.5% box- Before it was dissolved of 1992, the institute around 200 feature- I short films and docu- During the decade since established its official FONCINE (Fondo de Cinematogrifico) in institute has produced es and 125 shorts, partic- about 230 international and received more than ds internationally. In r several years of belt- measures, the federal nt raised FONCINE’s get from $1.2 million to on, while new funds- n a 1992 tax applied to VOL XXVII, No 2 SEPT/Ocr 1993 7SURVEY / FILM home video sales-were also tar- geted to increase national production.

With the arrival south of the border of the video cassette recorder and cable television, cinemas have been closing at a rapid rate. Over the past two decades the U.S. film industry has dominated this shrinking number of Latin American screens with blockbusters by offering attractive film-distribution packages. With a typical six- month window between a film’s U.S. screening and its release in Latin America, domestic exhibitors prefer to show these sure- fire hits rather duced Mexican genre films screened without subtitles-so U.S. majors can skirt reciprocal legislation. The New Latin American Cinema Foundation was created by rep- resentatives from all Latin Ameri- can countries to develop celluloid cultural identity and to confront distribution and exhibition prob- lems facing local film industries. One of the foundation’s first official acts was the opening of the New Latin American Film and TV than take a chance with nationally produced films that have yet to prove their market 0 value. Also, unlike cash-starved Latin American film Hugo Soto and Noemi Frenkel in the Argentine film, “Las Oltim naufragio” (1989), directed by Eliseo Subiela. productions, U.S. movies usually arrive accompanied by a complete publicity package, including film clips, press kits, stills, soundtrack albums and T-shirts.

Further tipping the scales in their favor, U.S. films are not dependent on foreign sales because produc- tion costs have already been recouped in the home market. Foreign sales of these films are mere gravy. Yet, for Latin America, the high cost of film production, plus subsequent advertising, makes it difficult for most countries to recoup their investment from the national market alone. In addition, the large Latino population in the United States provides a sufficient market for Latin American film production-mostly cheaply pro- School, a.k.a. the Three Worlds School, to train-on a scholarship basis-aspiring Latin American, Asian and African filmmakers and film technicians. Located in the Havana suburb of San Antonio de los Bafios, the media learning center boasts an international cadre of instructors dedicated to elevating the overall technical quality of cinema and television.

One major aim of the foundation is to break the U.S. majors’ virtual monopoly on distribution and exhi- bition in Latin America. Garcia MArquez notes that the foundation does not wish to drive the majors out, but wants only to be able to distribute and exhibit films with the same freedom as U.S. companies. Through meetings and accords, Latin American filmmakers and film policymakers are working to unify production and distribution measures on a continent wide level. To achieve this, the foundation sponsored a first integration forum in Caracas in 1989 called the Conference of Ibero-American Cinema Authorities (Conferencia de Autoridades CinematogrAficas de Iberoamdrica, or CACI). The foundation hopes to unify the diverse film industries through legislation to establish a Latin America common market for films, and through easing coproduction restrictions between Spanish- and Portuguese- speaking countries. The participants signed three documents at the introductory meeting. First, 13 countries signed the Ibero- American Cinema ias imagenes del Agreement, a pact which created two permanent organizations: a film conference that meets annually to evaluate the health of the industry, and an executive body responsible for ratification of CACI measures in each country’s laws. Twelve coun- tries endorsed a Common Market Agreement, an initial plan that includes four titles, which would receive all the protection and legal benefits that a national film receives in its domestic market. Limiting the number of titles pro- tects countries with modest levels of production: Venezuela, for instance, makes about 10 films annually compared to Mexico’s approximate 80 or Argentina’s 20. The small scale also works as a guard against the market being inundated by quickly produced industry pulp and cheap exploitation films.

CACI participants also signed a Coproduction Agreement. Coproductions are a logical method of feature-film production, since economic and technical resources can be shared while exhibition markets are doubled. The agreement allows up to five countries to participate in a given film project, permitting countries with developed industries to work with countries whose film production is still in its infancy. On the downside, many countries still have legal protectionist measures that regulate coproductions, specifying what is or is not acceptable to their industries.

Venezuela’s FONCINE hosted two CACI meetings in 1989 and 1991. Meetings were also held in Cartagena, Colombia and the island of Martinique in 1992 and in Spain in 1993. At these meetings, representatives from most Latin American countries agreed to promote coproductions and to form a mercomtina common market-in which Latin American films would pass freely among signatory countries.

Besides sponsoring CACI, the New Latin American Cinema Foundation is busy coordinating coproductions, cataloging and assembling a single Latin American film archive, holding seminars, and working with outside groups such as the Sundance Institute in Utah.

As Europe edges toward greater political and economic union, Latin America is also moving toward greater regional integration with agreements such as the Andean Pact and Mercosur that ease trade and travel restrictions. Hopefully, as a result of these larger economic accords and the easing of East-West tensions, cinema may soon cross borders with the same ease as television programming. Many Latin American countries among them Venezuela, Colombia, Peru and Mexico are currently revising national cinema legislation to include CACI production and distribution provisions. With such achievements to its credit, the New Latin American Cinema Foundation’s dream of a robust, continent-wide film industry may one day become a reality.

Read the rest of NACLA’s Sept/Oct 1993 issue: “Peril And Promise: The New Democracy in Latin America.”