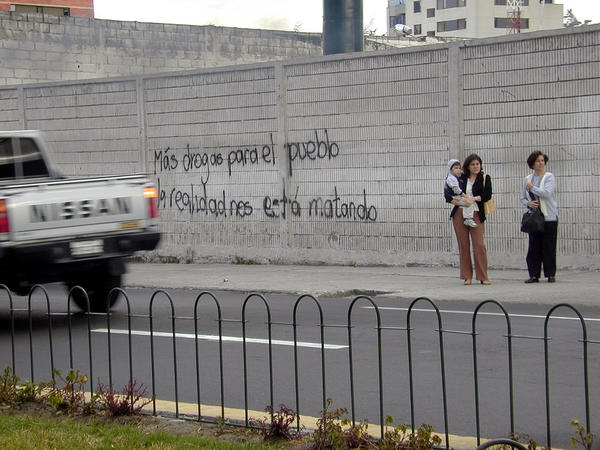

Graffiti reads “More drugs for the people because reality is killing us,” in Quito, Ecuador. (Matt Pounsett / Creative Commons)

Graffiti reads “More drugs for the people because reality is killing us,” in Quito, Ecuador. (Matt Pounsett / Creative Commons)

My father was imprisoned three and a half years for smuggling drugs to the United States. I felt this as a childfrom the age of 5 to 8, I lived without a father. He wasnt a criminal, he was unemployed. This experience, recounted by Ecuadors President Rafael Correa in the 2011 documentary Cocaine Unwrapped, propelled him to push for both penal justice and social rehabilitation reform. When you went to the prisons, especially those with women inmates, you didnt see the faces of delinquents or criminals, he said. You saw the faces of single mothers of the unemployed, of the poor. Not only did they lose their freedom, they lost their human dignity and we wont let this happen under our government.

Although Ecuador is not a major drug-producing or consuming country, Ecuadoreans have suffered one of the hemispheres harshest drug laws. The 1991 Law on Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, better known as Law 108, was passed at a time when U.S. pressure to fall into line with the repressive approach mandated by international drug control conventions was overwhelming. Law 108 has sentences that are disproportionate to sanctions for other crimes. The law also contradicts due process guarantees and violates the accuseds constitutional rights.

Law 108 does not distinguish the drug in question, the quantity of drug involved, or whether an alleged crime is violent or non-violent. All of those convicted of a trafficking offense are subjected to the same severe mandatory minimums of 12 years in prison. Furthermore, a drug trafficker can be indicted in multiple categoriesfor example, possession and transportand thus the sentences can sum up to a maximum of 25 years. As the minimum sentence for homicide is 16 years, someone convicted for a low-level drug offense, like small-scale dealing, can end up with a higher sentence than a murderer.

The laws success was measured by how many individuals were jailed. This resulted in major overcrowding and a significant worsening of prison conditions; the incarcerated population more than doubled in slightly less than two decades. By 2007, the percentage of persons in prison vs. those for which the prison system was built stood at 157%. Eighteen thousand people were detained in an infrastructure built to hold 7,000 inmates, resulting in the worst overcrowding in Latin America. In urban areas as many as 45% of imprisoned men are there on drug charges; for women, it reaches 80%.

Faced with this deteriorating situation, a task force established by the National Constituent Assembly (2007-2008) convened to review prisons and the penal code witnessed first-hand the appalling overcrowding, inhumane conditions, and the high percentage of prisoners incarcerated under Law 108. They approved a national pardon in late 2008 to cover everyone in prison for the trafficking or possession of illegal substances who met the following criteria: the prisoner had been sentenced, it was a first-time offense, the illegal substance involved was two kilograms or less, and the inmate had fulfilled at least 10% (or a minimum of a year) of the judgment. This historic step has helped to reduce some of prison overcrowding, explained Domingo Paredes, former head of the countrys drug agency, CONSEP, in Cocaine Unwrapped. The pardon had not only a humanitarian purpose, but a social one as well, because these imprisoned people had a one-time opportunity to re-insert themselves in society.

Once the Constituent Assembly approved the pardon, 2,300 people were released, according to the Ecuadoran Public Defenders Office. As of March 2010, the recidivism rate was under 1%. The pardon didnt reward us for being criminals, says former drug mule Nelsy in Cocaine Unwrapped. It just recognized that we are human beings who made a mistake.

The pardon was intended as a stop-gap while Law 108 was reformulated; however, it would be years before that happened and eventually the prison population shot right back up. It was not until 2013 that the National Assembly considered a revised penal code, presently being implemented, which incorporates drug crimes and replaces Law 108. That law mitigates significantly the disproportionality of Law 108, with sentences as low as two to six months for small-scale trafficking.

Because Ecuadorian law allows for more lenient legislation to be applied retroactively, anywhere from 1,000 to 7,000 prisoners could have their sentences reduced or be released, depending on judicial disposition. Rodrigo Vélez Valarezo, current CONSEP director, is also advocating for another pardon for those convicted of low-level drug offenses, noting that we must correct the injustices caused by Law 108.

Coletta A. Youngers is a Senior Fellow with WOLA, the Washington Office on Latin America, an associate with the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC), and a member of the research team, Colectivo de Estudios Drogas y Derecho (CEDD), based in Aguascalientes, Mexico.

Read the rest of NACLA’s 2014 Summer Issue: “Reimagining Drug Policy in the Americas“