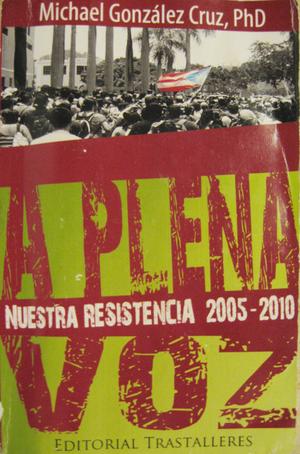

University of Puerto Rico sociology professor Michael González Cruz follows up his 2006 title Revolutionary Nationalism with A plena voz: nuestra resistencia 20052010, once again directing a frontal assault on colonialism and political repression in Puerto Rico.

The Spanish-language book is a collection of 22 articlesreprinted from outlets such as the San Juanbased newspaper Claridad and Cultura Venezolana magazinealong with a speech by González Cruz. The book begins by examining colonialism, anti-colonialism, and repression in Puerto Rico. The articles then cover issues surrounding Venezuelas Bolivarian Revolution and finally pay homage to the late Alberto Márquez, a committed island activist in Puerto Ricos independence movement. The book ends with a new piece written by the author in which he summarizes his key points and reiterates his proposal for a national united front to resist neoliberal policies and the continued colonial condition of the island.

The material documents not only the infamous actions of the FBI in its attempts to destroy the Puerto Rican independence movementoften violentlybut also the survival instincts of a movement that does not yield in the face of repression. González Cruz makes the connection between the historic struggles of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party (1930s50s), the underground armed revolutionary groups (1960spresent), and the mass political resistance in Puerto Rico today. Despite continued repression from the police and FBI, current activists are finding new methods of struggle and new ways of breathing life into Puerto Ricos historic revolutionary national movement of liberation.

The material documents not only the infamous actions of the FBI in its attempts to destroy the Puerto Rican independence movementoften violentlybut also the survival instincts of a movement that does not yield in the face of repression. González Cruz makes the connection between the historic struggles of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party (1930s50s), the underground armed revolutionary groups (1960spresent), and the mass political resistance in Puerto Rico today. Despite continued repression from the police and FBI, current activists are finding new methods of struggle and new ways of breathing life into Puerto Ricos historic revolutionary national movement of liberation.

González Cruz spends a good deal of attention on the life and assassination of Puerto Ricos legendary revolutionary fighter Filiberto Ojeda Ríos. From the 1960s on, Ojeda Ríos founded and led several underground revolutionary organizations on the island, including Los Macheteros, which was created in 1978 and carried out several assaults on U.S. military bases and other federal installations. Ojeda Ríos spent two major periods of his life underground and continued to call for revolutionary armed struggle to obtain Puerto Ricos freedom. In 2005, the FBI located and confronted Ojeda Ríos, riddling his home with over 100 bullets. Ojeda Ríos was shot in the clavicle, but medical attention was denied, and he bled to death inside his home. The attack outraged most islanders and galvanized the left. The death of Ojeda Ríos at the hands of the FBI highlights the themes of repression, colonialism, and popular struggle visited throughout the book.

The FBI has been the agency that has most consistently targeted social and political activists in the United States and its colony, Puerto Rico. As recounted in the chapter titled Fraticelli Partying? In the Rotary Club, the agencys former San Juan station director Luis Fraticelli publicly lamented, during a talk to Rotary Club members on October 3, 2006, that many Puerto Ricans consider Los Macheteros and the former Nationalist political prisoners heroes. Fraticelli did not explain how the agency planned to counteract this influence but took credit for ordering the assault on Ojeda Ríoss residence and refusing him medical aid when he was injured.

In an early chapter, The Political-Military Thought of Filiberto Ojeda Ríos, González Cruz discusses the political beliefs of the iconic Puerto Rican revolutionary, presenting them as a product of the decolonization struggles of a myriad of Latin American revolutionary figures, such as South American liberators Simón Bolívar, Antonio Valero de Bernabé (a Puerto Rican who served as one of Bolivars generals), and José de San Martín; Cubas José Martí; and Puerto Ricos Ramón Emeterio Betances and Pedro Albizu Campos. Ojeda Ríos believed in Pan-Americanism and international solidarity, and dreamed of realizing Martí and Betances dream of an Antillean Federation that would include Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Puerto Rico. The chapter also looks at Ojeda Ríoss support for armed struggle as a means of national liberation and his theory of revolutionary violence as merely a response to colonial state violence.

The states use of violence is an inevitable theme touched upon throughout A plena voz. According to González Cruz, the state views itself as the only legitimate arbiter of the use of violencedelegitimizing its use by the peopleand even curtailing basic rights and freedoms in order to preserve that right for itself. He highlights the 2005 assassination of Ojeda Ríos as a prime example of such state violence and places this within the context of the historic and violent repression of the independence movement on the island.

González Cruz also dedicates space to the popular struggle to end the Navys use of Vieques island as a bombing range. He writes that this inspiring mass campaign was not only devoid of the usual meddling and manipulation by political parties, but it was also part of the larger decolonization movement that saw liberating Vieques as linked to its anti-colonial struggle.

This effort contributed to the partial emancipation of our colonized nation, writes González Cruz, a prolonged battle by fishermen armed with slingshots, young people defending themselves with stones, Macheteros ambushing sailors, pacifists who disobeyed the unjust laws of the colonial regime, pastors who accompanied their people, and tens of thousands who marched armed with solidarity.

Aside from Vieques, González Cruz highlights various campaigns won throughout the modern history of Puerto Ricos independence movement, including community, environmental, and political struggles that he presents as indicators of progress in the fight for independence.

Among these victories is the Puerto Rican nationalist movements consistent resistance to the U.S. governments use of federal grand juries. From 1980 to 1985, more than a dozen Puerto Rican activists were imprisoned for their refusal to participate in a grand jury investigation into independence activists, presumably an effort to disrupt the activities of movement organizations. Following the assassination of Ojeda Ríos, another grand jury investigation in New York City attempted to summon Puerto Rican activists to inform on the activities of their peers, this time presumably to investigate support received by Ojeda Ríos and the work of Los Macheteros. Those young people also refused to participate, though none were imprisoned. Their defiant resistance was a major victory against the U.S. governments attempts to infiltrate the Puerto Rican independence movement.

In the chapter Students Under Watch, González Cruz writes about the series of Puerto Rican student strikes that shut down the university system on the island in 2010 and 2011. The police and government response was overwhelmingly violent and brutal. This student struggle, in particular, resonates with the title of the book: Our Resistance.

The theme of resistance continues with the chapter The Strike and the Macheteros, analyzing the notion of a general strike in Puerto Rico. It uses information gleaned from a published interview with the leadership of Los Macheteros in Claridad in late 2010 and the teachings of renowned national poet and veteran revolutionary nationalist leader Juan Antonio Corretjer. The analysis provides an interesting backdrop for the ongoing threats of stoppages and general strikes during the current economic crisis facing the island, as it includes information quoted straight from the most revolutionary forces on the island, whose communiqués are rarely examined in other texts.

There are five chapters dedicated to Venezuelas Bolivarian Revolution, in which the author seeks to shed light on the U.S. efforts to quash President Hugo Chávezs revolutionary politics. The final chapters are dedicated to elevating the status and notoriety of the late Alberto Márquez, a veteran Puerto Rican activist respected for his years of commitment to the independence struggle. Those wishing to better familiarize themselves with Márquez would do well to review González Cruzs lengthy, insightful interview with him printed in the book.

The author closes with an original essay, House Without Doors: The Front for National Salvation, a piece clamoring for ideological unity in the movement with an eye toward achieving the salvation of the Puerto Rican nation from colonialism and destructive neoliberal policies. The proposal of creating such a front was originated by Ojeda Ríos in 1989, and the author offers a dramatic appeal to continue the effort.

The message delivered out loud in this collection confronts the states attempt to repress an organized and formidable anti-colonial national liberation movement. In its confrontation with the states intelligence apparatus, the movement declares victory over the efforts to snuff out its life and its successes, sneering at the FBI with calls to action, mass demonstrations, communiqués, protests, analysis, and continued efforts to develop unity across the spectrum of the independence movement.

Now is the time to aim our weapons at the enemy, the time to overcome egoism and roll up our sleeves to obtain the support of the people, González Cruz declares. With great optimism, he does indeed aim the cannons of war at the enemy, exposing the political repression of the FBI against the right to self-determination of the people of Puerto Rico while celebrating the political victories of mass struggle on the island, akin to the Arab Spring and Occupy movements. His adherence to the political thought of the venerated revolutionary Ojeda Ríos, with special emphasis on the need for unity within the independence movement, is a call to overcoming egoism in the ranks. His report back on the revolutionary process in Venezuela is merely an offering of how a politically revolutionary front can reorganize national priorities to win the support of the people by meeting their long-term needs.

A plena voz is a call to arms to resist political repression and to struggle for civil and human rights in a country under colonial occupation and fighting for national liberation. History will certainly remember this exciting contribution to that humanistic global struggle.

Juan Antonio Ocasio Rivera is a Puerto Ricobased activist, social worker, and professor. He has written for several online publications, including CounterPunch, Upside Down World, New York Latino Journal, and was active in the New Yorkbased All of New York With Vieques.

For more on the subject see Our Resistance: An Interview With Rafael Cancel Miranda.

Read the rest of NACLA’s Fall 2012 issue: “#Radical Media: Communication Unbound.”