Forty years after the end of the Falklands Islands war on June 14, 1982, Argentina has petitioned the United Kingdom to rethink its relationship with the country and the future of the Falklands Islands.

In an opinion piece published in The Guardian on the eve of the anniversary, Argentine Foreign Minister Santiago Cafiero alluded to the lack of progress and absence of dialogue since the war: “The UK maintains a major military base in the South Atlantic, carries out periodic military exercises in the disputed area and maintains restrictions on the sale of dual-use military materials to Argentina.”

Despite Argentine requests for dialogue, so far, the United Kingdom has failed to respond to calls to revise British policy toward Argentina and the areas surrounding the islands. Even though the political climate and geopolitical relations in Latin America have shifted considerably since the mid-1980s, according to Cafiero, the United Kingdom “continues to act as though the conflict was just yesterday” and to sanction Argentina as though dealing with “severe human rights abusers.”

A Conflict with No Clear Winners

Over 500 years, various colonizers have laid claim to the Falklands. The French established a colony called Íles Malouines on East Falkland in 1764. The British set up an outpost on West Falkland shortly after, until the Spanish, who had taken over the French colony, forced the British out in 1770 by turning up via Buenos Aires with a fleet of 1,400 soldiers. In 1811, the Spanish dismantled their settlement, leaving behind a plaque that claimed sovereignty over the island, as the British had done previously. To date there is no concrete evidence of pre-Colombian settlement, though research suggests Indigenous peoples did step foot on the islands prior to Europeans.

Generations later, the 1982 Falklands conflict took place as ferocious right-wing dictatorships gripped Southern Cone countries, including Argentina, and hard-line Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher struggled to stave off internal challenges to her premiership in Britain. After decades of unresolved disputes, Argentine troops occupied the Falklands, known in Spanish as Las Malvinas, on April 2, 1982. The United Kingdom retaliated, and a short but bloody war ensued.

At the time, most Latin American countries supported Argentina’s claim of sovereignty over the islands, except for Chilean dictator General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990), who became an indispensable British ally. Declassified documents show that Chile intercepted Argentine commands and provided vital intelligence leading to the sinking of the Argentine naval cruiser General Belgrano, in which 323 people lost their lives. This act of loyalty cemented Thatcher’s “special relationship” with Pinochet, who she would later fervently defend when he was arrested in London in October of 1998 for crimes against humanity.

On June 14, Argentina surrendered. The toll of the conflict was heavy: 255 British soldiers, 649 Argentinian military personnel, and three Falkland Islanders were killed during the 74-day conflict. The United Kingdom regained control of the islands, but the sovereignty dispute remained unsettled, and in recent years Argentina has renewed its claims.

For Eduardo Ortuondo, an Argentine veteran, the legacy of the war is complicated. “To all of us the Malvinas were, are and will be Argentinianand we went to fight full of patriotic pride,” he told The Guardian. “We knew that they [Argentina’s military regime] were capable of all kinds of barbarities, but we thought that they would look after their own troops.”

During the war, Ortuondo was tortured by his commanding officer for licking a jar of marmalade because he was desperately hungry. The ill treatment of the ranks of some 10,000 Argentinian conscripts at the hands of dictator Leopoldo Galtieri has been well documented. Painful memories of the systemic brutality of the Argentinian army towards its own poorly equipped, ill-fed troops continue to resurface, as former soldiers persevere with their claims for justice at the Supreme Court in Buenos Aires.

While the triumph of the British army in securing sovereignty over the Falklands bolstered Thatcher’s ailing political career, the loss of control over the islands cemented the downfall of Galtieri’s heavily critiqued regime for its handling of the operation. Shortly afterward, the Argentine dictatorship that had claimed over 30,000 lives during the “dirty war” began to unravel. Galtieri was forced to resign three days after the war ended and went into hiding for 18 months while democracy was restored.

In 1983, Galtieri was arrested after the Rattenbach Report, commissioned by General Rattenbach to investigate the causes of the Falklands military defeat, found Galtier responsible for mismanagement of the war operation and human rights crimes. Although convicted and imprisoned for incompetence in 1986, he was pardoned by President Carlos Menem in 1999. He was arrested again in 2002 for crimes against humanity and lived under house arrest until his death from pancreatic cancer in 2003.

Prestige, Oil, and Geopolitics

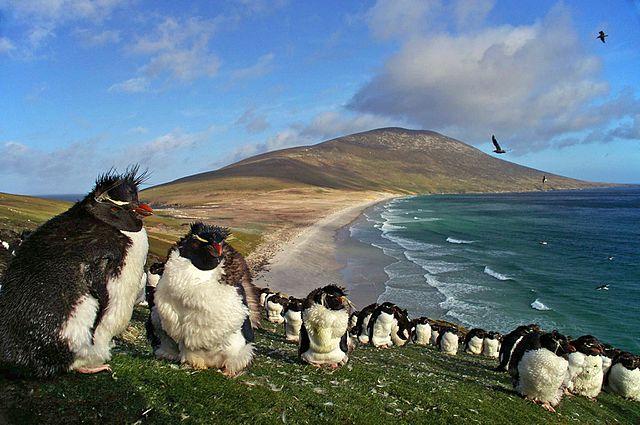

Today, most of the Falkland archipelago’s 3,398 inhabitants are native-born Falkland Islanders who, under the 1983 British Nationality Falkland Islands Act, have claim to British citizenship. A 2013 referendum found more than 99 percent of Falkland Islanders wish to remain a British territory.

The United Kingdom’s points to the 2013 poll to justify its claim to the territory. “The United Kingdom has no doubt about its sovereignty over the Falkland Islands and surrounding maritime areas, but it is up to the Falkland Islanders to determine their own political status,” a foreign and commonwealth office spokesperson said, citing the 2013 result.

While the Falklands’ location may not be of huge geopolitical significance today, there are other motives for the United Kingdom wanting to retain sovereignty. Grace Livingstone, author of the book Britain and the Dictatorships of Argentina and Chile, 197382, highlighted political backlash and oil interests as key factors.

“Declassified British government documents show that the primary reason that British politicians have sought to maintain sovereignty over the Falkland Islands is the fear of a political outcry at home if they abandoned the Islanders,” she explained.

“However, the documents also show that both before and after the Falklands War, the British government and British oil companies were keen to explore oil resources around the Islands and to ensure that Britain got the lion’s share of any oil revenues,” she added. “Britain has claimed a 200-mile zone in the waters around the Falkland Islands to explore for oil and other resources. Since 1996, the Falkland Islands Government has been unilaterally drilling for oil in this area.”

Ocean oil exploration surrounding the Falklands picked up in the 2010s with the drilling of the Sea Lion oil field, which is estimated to hold some 1.7 billion barrels of oil. In addition, 200 kilometres to the north of the islands, it is estimated that there are 325 million more barrels of recoverable oil.

New Politics for a New Era

Today’s Latin American geopolitical climate starkly contrasts the authoritarian dictatorships of the Cold War era. Argentina has a moderate government headed by center-left Peronist Alberto Fernández, and Chile recently inaugurated as president ex-student leader Gabriel Boric, a progressive who has pledged to transform Chile’s radical neoliberal economy and oversee the removal of the dictatorship-era constitution.

At the beginning of April, Boric was in Argentina on his first international presidential visit. A self-proclaimed Latin Americanist, he was clear in his support for Argentina. He told the press: “I support in a clear and decisive manner the revindication of the Malvinas by the Argentinian government, people, and state.”

Argentine Foreign Minister Cafiero’s insistence on talks to redefine the sovereignty of the islands is also supported by the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization, which approved a draft resolution in 2019 restating a need for a peaceful, negotiated settlement over the Falkland Islands.

Anglo-Argentine activist Pablo Bradbury stressed that while the UN has been consistent in calling for negotiations, the United Kingdom’s “continuation of colonial rule” remains “incompatible with peace.”

“The UK pretends the 1982 war settled the issue, which is not the way that such disputes should be resolved,” he said. “The maintenance of a major military base [in the Falklands] and the regular military exercises are simply not acceptable and will inevitably be taken as provocations by Argentina and other Latin American countries.”

“The islanders may want to remain British, and their wishes obviously have to be recognised, but the 2013 referendum doesn’t settle the issue from a political or a legal standpoint,” he added.

The interests of all stakeholders and climate in which they operate are vastly different than they were in 1982. In a post-pandemic world, where resources are scarce and international cooperation is vital, Britain must seek a diplomatic solution to the enduring Falklands Islands dilemma and seek to redress its colonial legacy.

Carole Concha Bell is an Anglo-Chilean writer and PhD student at King’s College London. She is a specialist on the Mapuche conflict and socio-political conflict in Latin America.