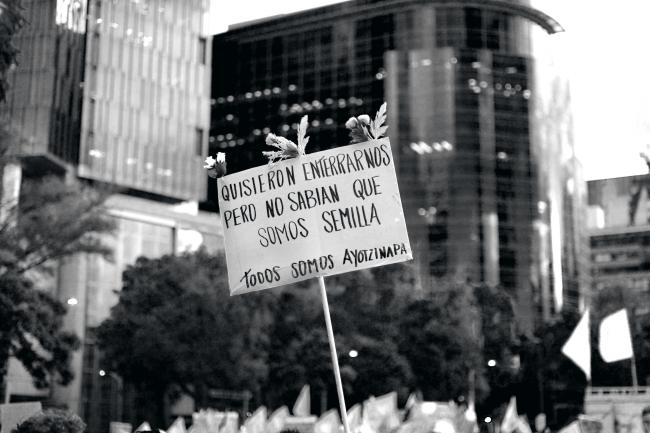

This month marks four years since the brutal attack on the students from the Aytozinapa rural normal school, a teacher training college in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, in which six people were killed and forty-three students were forcibly disappeared. After all this time, and after multiple investigations, there is still no definitive explanation of what happened that night in 2014 in the small city of Iguala: Who took the students? Where were they taken? What happened to them? More than one hundred people have been arrested in connection with the Ayotzinapa attack, but despite this, students’ families still lack answers to these most basic questions.

The families are joined in their struggle for answers by human rights groups, international legal experts, and fearless journalists, perhaps most prominent among them Anabel Hernández, whose book about the Ayotzinapa disappearances, A Massacre in Mexico: The True Story Behind the Missing 43 Students (Verso), is out in English this fall. While there are few new revelations in the book (it was published in Spanish in 2017 and is based on reporting Hernández has undertaken since the attack) it is the most comprehensive account of what is known about the attackand about the astonishingly corrupt government investigation that followed.

That investigation is the real subject of the book. The families’ frustrations derive not just from not knowing what happened to their sons, four years on, but also from the fact that they must undertake their struggle for truth against their own government, which has, at every turn, stymied their search for the truth.

Hernández shows why, in painstaking detail. A Massacre in Mexico presents an overwhelming case that federal government investigators working for the administration of Mexican president Enrique Peña Nieto created a false narrative of local culpability and sought to close the case before an investigation could reveal the involvement of federal officials.

The federal government contended that the Iguala mayor demanded the municipal police intercept the students because he feared the disruption of a political event being held by his wife. The police then handed the students over to a local drug gang; the gang then killed the students and burned their bodies in a massive fire in a garbage dump in the nearby town of Cocula.

Mexico’s attorney general sold this “historic truth” to the public on the basis of confessions of supposed gang members, as well as video evidence, and, eventually, the DNA of one of the disappeared students, extracted from a bone fragment recovered from a plastic bag thrown in a river next to the garbage dump.

But in the months after the attack, Hernández and her colleague Steve Fisher quickly obtained evidence that demonstrated that aspects of the federal government’s story couldn’t be true.

While the federal investigators had insisted that only local and state-level security forces were present when the attack began, Hernández and Fisher revealed, in an article in Proceso magazine in December 2014, the existence of a coordinated command-and-control center in Iguala. There, local, state, and federal officialsincluding police, military, and judiciary personnelnot only monitored what was happening in real time, but had in fact been watching the Ayotzinapa students since well before the attacks began. She revealed that the Mexican Army and federal police were on the streets of Iguala during the attack and published terrifying cell phone footage taken by students under attack, in which they denounce the presence of federal officials while taking gunfire.

Hernández and Fisher’s report was explosive, causing a massive outcry in Mexico and around the world. A team of expert forensic investigators from Argentina had already concluded that there was no evidence of the massive fire necessary to burn forty-three bodies, and warned that they couldn’t verify the chain of custody of the bone fragment that held the DNA of one studentmeaning it could have been planted.

A team of independent international experts had begun their own investigation and confirmed many of Hernández’s findings, including a report she published alleging the widespread use of torture against those accused of participating in the attacks. A Massacre in Mexico details this torture at horrific length, and calls into question nearly all the arrests that have been made in the case. From the earliest arrests, Hernández reveals, security forces, including federal police and military officers, used brutal torture methods to extract confessions from supposed gang members, including waterboarding, rape, and electrocution.

All told, there are 33 confirmed people in detention who are known to have been tortured in government custodyand in at least one case, a suspect was killed during a raid by the Marines, who, according to witnesses, threw the suspect’s tortured body out a window in an attempt to cover up his murder.

The stories of three men arrested in October 2014 and accused of being the “material authors” of the killing and burning of the students in the trash dump are particularly devastating. All three were construction workers, living near one another in the town of Cocula, and all three were desperately poor. Hernández describes, for example, the possessions seized from the men when officials searched their leaky, tin-roofed homes: among the few things of value seized by the state in one home was an electric fan, still being paid off in installments.

All three men were visibly injured when their confessions were tapedthe international investigators counted 94 wounds on one and the confessions contain serious discrepancies between them. None of the men had sufficient resources to hire a lawyer to defend themselves. But they were placed at the center of government’s official story, and remain imprisoned, even as UN human rights investigations have been opened into their torture.

Beyond the extraction of confessions through torture, Hernández also describes in meticulous detail the many other ways in which federal officials impeded the investigation, including mishandling forensic evidence, doctoring video, and refusing investigators access to crucial sites like the Army base in Iguala, which was not inspected after the attacks.

A particularly egregious instance concerns Mexico’s chief criminal investigator, Tomás Zerón, a longtime friend and ally of President Peña Nieto (“He knows everything about the president,” one source told Hernández). It was Zerón who supposedly found the bags containing bone fragments at the Cocula dump site, where the DNA of one student was recovered.

After months of public outcry, the attorney general’s office had agreed to allow its own inspector general to conduct an internal assessment of the investigation to that point. That assessment would eventually find that that Zerón had violated victims’ “right to the truth” and argue that he may have tampered with evidence (an allegation also made by the international investigators).

But the inspector general’s report was buried: when its conclusions were presented internally in August 2016, the attorney general argued that Peña Nieto himself would have to personally sign off on it before it was released. The president declined to release the report implicating his old friend, and while Zerón was subsequently removed from his post as chief criminal investigator, he was immediately given a new position on the National Security Councilin the office of the president.

With these and other details, A Massacre in Mexico illuminates why there are still so many unanswered questions about what happened on the night of September 26, 2014. From the first moments, federal officials used all available means to obfuscate the truth and shield their agencies and colleagues from scrutiny. The military, the federal police, the attorney general, and even the president himself staked their claims on a vast and sprawling lie, one whose extralegal operations and internal contradictions would be its own undoing.

This bookmore dossier than narrative, exhaustive in its detailcondenses the evidence that, as activists have argued since the attack, the culpability lies with the state: “fue el estado.“

The impunity that is so endemic in Mexico has so far shielded federal agencies from scrutiny; in order to find out what really happened to the Ayotzinapa students, Hernández clearly believes, you have to uncover how, and why, the state built its false narrative in the first place.

Still, the issue of motive underlies one of the most haunting unanswered questions: why were these young menteachers in training, the children of impoverished peasantsso brutally attacked? What justification could be given for this level of violence?

The international investigators pointed to the possibility that the students had inadvertently commandeered a passenger bus that was carrying an important narcotics shipment. Long-distance bus lines in Mexico are frequently used to ship lucrative drugs, and Iguala had become an increasingly important transshipment point for heroin destined for the United States.

Hernández confirmed this motive: she was able to meet multiple times with a drug trafficker loosely associated with the Beltran Leyva cartel who claimed not only that his heroin shipment was on a bus taken by the students, but also that he kept Mexican Army and federal police forces, as well as local officials, on his payroll. Upon learning that the students had commandeered a bus carrying some $2 million worth of heroin, the trafficker dispatched an army commander to get the drugs back.

He didn’t want the violence, and certainly not the disappearances: that would be “heat[ing] up the plaza,” as he told Hernández. But he sent the Army out that night, and told Hernández that he had heard that the students were taken to the military basewhere commanders refused inspection during the investigation. The Army, the trafficker said, took it too far. (This motive seems to be corroborated by recently released DEA surveillance of drug traffickers in Chicago discussing the disappearance in real time).

The drug connection helps to explain why the students were attacked with such ferocity. But there is another, broader motive for the violence, one that Hernández has stressed since the early days of her investigations, and one that she emphasizes here: the political nature of the Ayotzinapa students’ activism.

The school has a long history of fomenting resistance in Guerrero, and Hernández details how President Enrique Peña Nieto had Ayotzinapa in his sights from the earliest days of his administration.

Before Peña Nieto even took office, the advisors of the outgoing and incoming presidents met in November 2012 to draw up a list of national security priorities for the coming term. As Hernández reports, the seventeen-page document makes no mention of people like Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán or cartels like the Zetas.

Instead, second on the list of “governability” problems of national concern were the students of the Raúl Isidro Burgos Normal School of Ayotzinapa. The students were not just dangerous, according to the federal government; they were threats to national security.

So, on September 26, 2014, as Hernández shows, federal, state, and local forces were watching the students’ every move, long before they entered Igualahaving been primed to see the young men as enemies. The state created the conditions for the attack, then worked desperately to hide the machinery that undertook it. The president, the attorney general, and military leaders raced to cast blame downward, onto local officials and, more tragically, onto local residents too poor and powerless to defend themselves. Over these last four years, officials who dared to question the official story were sacked, and international investigators were thrown out of the country.

Whatever happened on the night of September 26, 2014, the Peña Nieto administration did everything in its power to make sure that the truth would not come to light. But thanks to the tireless advocacy of the students’ parents, activists, and journalists like Anabel Hernández, the search for the truth continues.

In June, a federal court in Mexico shocked the country by ordering that the investigation into the Ayotzinapa attack be reopened and demanding the establishment of an Investigative Commission for Justice and Truth, independent of the attorney general’s office, to oversee it. There is hope that such a body will be constituted under the new administration of the recently elected Andres Manuel López Obrador and will begin to explore the allegations that Hernández and the international investigators have laid out.

As the parents of the missing students so often chant when they march, demanding answers, the struggle continues: “Ayozti vive, la lucha sigue.“

Christy Thornton is an assistant research professor in sociology and Latin American studies at Johns Hopkins University.

This piece was published as part of a collaboration with Jacobin magazine.