As the Organization of American States (OAS) begins its 51st annual General Assembly today, one of the important disagreements that will certainly feature prominently is the OAS role in Bolivia in 2019. Like the September 18 summit of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), the OAS General Assembly is sure to be marked by the polarized nature of international politics in the region, and the issue of Bolivia has already been at the center of heated discussions among ambassadors in OAS Permanent Council meetings. The current Bolivian government refuses to let the matter rest until it has obtained a full investigation into the OAS’s role in the coup that brought Jeanine Áñez to power two years ago.

In the last few weeks, several events have brought the coup back to the forefront of regional politics. In August, an interdisciplinary group of independent human rights experts, known as the GIEI for its initials in Spanish, released its report on human rights violations committed during the crisis surrounding Bolivia’s 2019 elections. Among its many findings, the 468-page document clearly establishes that Bolivian state security forces perpetrated “massacres” following the coup. The report outlines a number of recommendations regarding the treatment of victims, calls for the perpetrators of human rights violations to be held accountable, and denounces the prevalence of pervasive racism in the Bolivian state and society.

The GIEI report has been well received by the international community. It was welcomed by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, which highlighted its conclusion “that serious human rights violations, including systematic torture, summary executions and sexual and gender-based violence, took place in the Plurinational State of Bolivia during the post-electoral crisis in 2019.” The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which is formally an appendage of the OAS but enjoys autonomy from the OAS Secretary General’s office, has also been highly supportive of the GIEI’s work, findings, and recommendations. It was the IACHR, under the leadership of former Executive Secretary Paulo Abrão, that pressured the Áñez government to agree to the creation of the independent group of experts to investigate human rights violations.

The IACHR’s endorsement of the GIEI report has been unambiguous. Its president, Antonia Urrejola, and two vice presidents spoke at the August 17 ceremony in La Paz where the GIEI formally presented the report to Bolivian President Luis Arce. For former IACHR leader Abrão, who attended virtually, the release of the report must have been a vindication of sorts. In August 2020, OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro removed Abrão from his position as IACHR executive secretary on the grounds of alleged workplace harassmentaccusations that were never investigated. IACHR members opposed the decision to remove Abrão and complained that the non-renewal of his contract was carried out “without any prior consultation” with the IACHR. They considered this to be a “serious attack on [the IACHR’s] independence and autonomy.” UN High Commissioner on Human Rights Michelle Bachelet, along with several human rights organizations, also decried Almagro’s unprecedented encroachment on the IACHR’s historical autonomy.

At the time of Abrão’s removal, then president of the IACHR, Joel Hernández, warned that Abrão’s dismissal could be politically motivated. Hernández specifically referenced the strong pushback from several right-wing governments that Abrão had accused of serious human rights violations: Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Paraguay, and not least, Abrão’s home country, Brazil. It’s also likely that Abrão’s denunciation of the Áñez government’s human rights record in Bolivia in 2019, and his criticism of the violent crackdown on protests in Ecuador that same year, made him a target of those governments as well. These governments, as well as the Trump administration, which unconditionally supported the Añez government, were strong allies of Almagro. With the exception of Argentina, where a new government took office in December 2019, they all voted for Almagro’s reelection as OAS secretary general in 2020.

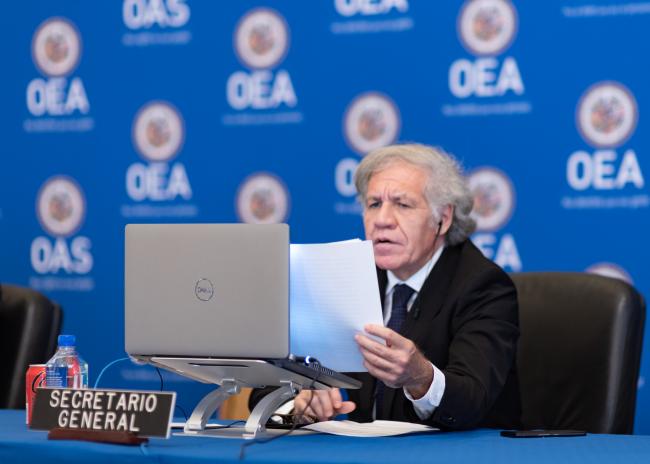

In stark contrast to Abrão’s denunciation of the Áñez government’s abuses, Almagro played a key role in supporting her de facto government in 2019 and 2020. He refused to call her accession to power a coup and ignored the allegations of egregious human rights violations. But in sync with his trademark opportunism, Almagro reacted to the launch of the GIEI report by tweeting: “We have taken note of the publication of the GIEI Bolivia report. While there will have to be further analysis in the coming days, we believe that it contains important elements that need to be referred to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ)”.

While Almagro has made a U-turn on his support for Áñez and her collaborators, his persistence on the fraud narrative in the 2019 Bolivian elections has endured. Several academic studiescarried out by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) and scholars from MIT, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Tulane, eventually reported on in Washington Post and The New York Times, respectivelyclearly demonstrate that the main OAS claims regarding the 2019 Bolivian elections were unfounded. On October 22, Bolivia, Mexico, and Argentina hosted an event in the OAS’s Hall of the Americas where a panel of experts presented their findings on the OAS’s vote manipulation claims. Their conclusions crushingly admonished the methodological flaws, and even outright lies, of the OAS reports and delivered a scathing critique of both the OAS’s amateurish statistics and its so-called forensic evidence.

Almagro, however, has refused to accept these expert findings or allow for any serious independent investigation into the OAS claims, as countries like Mexico have formally requested. Recognizing that the OAS was wrong and even lied would most likely lead to Almagro’s resignation and an opprobrious end to his political career.

What’s Next for Almagro?

Almagro can still find solace in the fact that much of the media has yet to acknowledge that the OAS fraud claims have been debunked by multiple independent studies. Many media outlets backed the OAS fraud narrative in 2019, which means few journalists are now eager to admit they were mistaken. Almagro is also shielded by the current balance of powerand votesin the OAS Permanent Council of member states. Even in the context of the recent electoral triumphs by the Left in several countries in the region, conservative forces still have a majority in the organization.

Still, the Bolivia issue recurrently comes back to haunt him. At an August 25 extraordinary OAS Permanent Council meeting, representatives of Argentina and Mexico joined Bolivia’s foreign minister and minister of justice in denouncing the role of the OAS in Bolivia’s 2019 political crisis and in calling for Almagro to be held accountable. Almagro deferred to his lieutenant, the secretary for the strengthening of democracy, Francisco Guerrero, who uttered a few technical falsehoods. Among other claims, Guerrero suggested that the disappearance of electoral material in Bolivia after election day was proof of fraud, when it is well-documented that the missing election material was destroyed by angry Morales opponents, who burned down several vote-counting stations, in part egged on by OAS claims of wrongdoing.

Although a few right-wing governments did lend the beleaguered Almagro some enthusiastic backing, most of the support was lukewarm. Several members highlighted the historical role the OAS has played in elections in the region, rather than saying anything about the OAS’s 2019 reports on Bolivia.

Conspicuously, Almagro’s most aggressive advocate at the August 25 meeting was the representative of self-proclaimed Venezuelan leader Juan Guaidó. Guaidó’s representative still sits on the Permanent Council despite the serious erosion of Guaidó’s position in recent months: Guaidó is no longer an elected representative in Venezuela’s National Assembly, the bulk of the Venezuelan opposition to Nicolás Maduro does not support him, and as time passes, fewer governments recognize him as president. While most other representatives of right-wing governments stuck to the usual platitudes in support of the OAS’s generic role as an electoral observer, Guaidó’s representative, the one with the most to lose from Almagro’s potential fall from grace, denounced a “campaign to discredit Almagro.” He also decried that “what happened on October 20, 2019 [in Bolivia] was a transparent attempt at electoral fraud.”

The only other official at the meeting to explicitly defend Almagro’s specific positions on Bolivia in 2019 was the U.S. interim representative to the OASa Trump administration hold-overwho went so far as to note the “remarkable work of the OAS election observation mission in Bolivia” and the “OAS’s exceptional commitment to support Bolivian electoral processes amidst concerted politicized efforts to falsely undermine its work and reputation.” He went on to lament the “repetition of a false electoral narrativein this case, the golpe de estado in Bolivia in 2019.”

The Biden administration, however, is slowly finding that it is not just a group of Latin American governments that are unwilling to brush aside what happened in Bolivia in 2019; Democrats on the Hill are increasingly voicing their concern that the previous administration’s positions on Bolivia still persist. In July, the U.S. House of Representatives passed language put forward by Congressmembers Jan Schakowsky (D-IL) and Susan Wild (D-PA) urging the State Department to investigate the role of the OAS in Bolivia’s 2019 elections and human rights crisis. In October, it was the U.S. Senate‘s turn. The Appropriations Committee expressed concern about “the political crisis that followed [Bolivia’s 2019 elections], and the role of the Organization of American States electoral observation mission in that process.” Significantly, the Senate committee directed the secretary of state to assess “the transparency and legitimacy of the elections,” including the role of the OAS, and “progress in investigations of responsibility for violations of human rights,” with attention to the GIEI findings.

The State Department now has an obligation to act upon a congressional directive that clearly mandates an independent investigation of the OAS’s role in the coup. Whether the Biden administration will stick to denying facts and blindly supporting Almagro, as the Trump administration did, remains an open question, contingent in part on what Biden’s Western Hemisphere appointees will do once they are finally in place. The OAS General Assembly is certainly an opportunity for the United States to start showing signs that the new administration is different from the last in its approach to the hemisphere. The U.S. government should also understand that questions regarding what happened in Bolivia in 2019 are not going to go away any time soon.

Guillaume Long is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) in Washington D.C. He was Ecuador’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.