This investigation was originally published in Spanish by Quinto Elemento Lab on September 26, 2023. This is Part I of a three-part English translation.

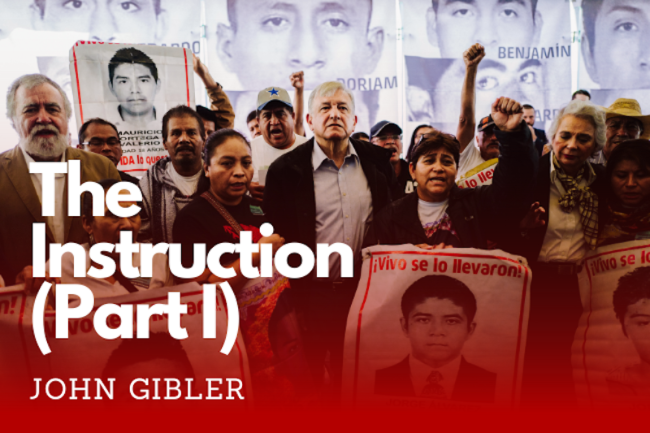

From a city in the United States, Omar Gómez Trejo, former head of the Special Investigation and Litigation Unit for the Ayotzinapa Case, details how a “State decision” made it possible to cancel in 2022 the arrest warrants against 16 military personnel and to put together in 24 hours the arrest warrant for former Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam, the author of the “historical truth.” This is Part I of the story of how the Mexican government dismantled the team in charge of investigating the forced disappearance of the 43 students.

On Friday, August 12, 2022, Alejandro Gertz Manero, the octogenarian attorney general of Mexico, called the then head of the Special Investigation and Litigation Unit for the Ayotzinapa Case (UEILCA), Omar Gómez Trejo, to his office.

“Omar,” Gómez Trejo said the prosecutor told him, “I need a favor, a worksheet where you tell me how the case is going, what’s going on, what progress is being made. I have a breakfast next Monday.”

For three years, Gómez Trejo, a 43-year-old human rights lawyer with a gray beard and tattooed arms, had been at the helm of the most extensive, complex, and arduous legal investigation in recent Mexican history: the forced disappearance of 43 students from the Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College in Ayotzinapa during the long night of September 26-27, 2014.

Gómez Trejo didn’t know it then, but that breakfast would be attended by President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Interior Minister Adán Augusto López, Supreme Court Chief Justice Arturo Zaldívar, and Deputy Secretary of Human Rights Alejandro Encinas. He had no way of knowing it then, but during that breakfast meeting, Mexico’s highest public officials would all agree to a series of actions that would blow up the Ayotzinapa investigation and provoke his departure from the country.

So, unaware of what was to come, that summer Friday on the 25th floor of the Attorney General’s Office (FGR), Gómez Trejo told his boss that yes, he’d get right to it.

The Years of Terror

Around 5:30 p.m. on September 26, 2014, two buses of students left Ayotzinapa. The students had been trying for days to get buses and organize a caravan from the country’s rural teacher training colleges. They planned to travel from Ayotzinapa to Mexico City to participate in the march commemorating the October 2, 1968 student massacre in Tlatelolco.

Between 7:30 and 8:00 p.m., the two buses separated; one stayed at the Huitzuco intersection, a place known as Rancho del Cura, and the other headed to the Iguala toll booth. The students did not know that they had been infiltrated and identified, and that they were being monitored by military intelligence agents. And they had no way of knowing that the commanders of the two Army battalions in Iguala, the 27th and 41st, and many of their subordinates were part of an illegal enterprise known as Guerreros Unidos, which trafficked heroin from the mountains of Guerrero to the barrios of Chicago.

About an hour later, Ayotzinapa students took three more buses from the Iguala bus station and left for the highway by two different routes. Iguala police chased them and attacked them with gunfire, stopping the five buses in two different places. Police from nearby Huitzuco and Cocula, state and ministerial police, federal police, and soldiers arrived at different times to support or observe the attacks. None intervened in favor of the students. The police subdued and took 43 the students from two of the five buses.

The attacks lasted all night. Journalists, civilians, and a soccer bus were also attacked. In the predawn hours it began to rain. When a group of reporters from the state capital of Chilpancingo arrived, they saw some of the wounded from the soccer team, the police checkpoints, the lifeless bodies of two students in the street, and masked soldiers moving in the shadows.

The first news reports were confusing. Uncertainty grew. But from the very beginning, the survivors and other witnesses said that it was police who had attacked them and who took the 43 students.

Confronted with the facts, state policy during the government of Enrique Peña Nieto was to lie. To sustain the lie, the federal authorities in charge of the investigation tortured detainees, invented a crime scene, threatened witnesses, destroyed and planted evidence, falsified documents, hacked and spied on journalists, investigators, and the lawyers of the families of the disappeared students, and even killed and disappeared witnesses and people involved in the attacks.

In those years, from 2014 to 2018, the government insisted on its integrity and good will while inflicting torturein sessions recorded by security agentsand lying. They had the audacity to baptize their policy of deception as “the historical truth.” And neither the testimonies of survivors and witnesses, nor the journalistic investigations, nor the first two reports of the Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (GIEI)created by mandate of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)provoked more than minimal adjustments to their lie.

They were years of terror.

The Commitment

From the beginning, López Obrador’s relationship with the struggle of the families of the 43 disappeared students was one of tension and distance. During the years of terror, his position was above all characterized by silence.

That was until May 25, 2018, when at a campaign event of the then-presidential candidate in Iguala, a commission of mothers and fathers of the disappeared students went on stage and asked him to take a stand. There, for the first time, López Obrador pledged to investigate the case and create a truth commission led by the IACHR and the United Nations.

“Since then, the president publicly stated that he was going to promote a truth commission,” says Santiago Aguirre, lawyer for the families and director of the Miguel Agustín Pro Juárez Human Rights Center (Centro PRODH). “The mothers and fathers, in good measure with the accompaniment of Tlachinollan [Human Rights Center] and the Centro PRODH, from that moment on said ‘No, here there is an issue of pending justice.’ The government should not only focus on clarifying the truth, but also on pursuing justice.”

Mario González, father of the disappeared student César Manuel González Hernández, told me in 2018 that he did not look favorably on the then-candidate’s proposal: “More than the truth commission, what we want is the truth. We already have the commission. We would have to start from the recommendations and investigations of the GIEI.”

López Obrador repeated his commitment on September 26, 2018, as president-elect. For the first time in the four years since the forced disappearance, he appeared alongside the families at a protest event: “We are going to know what really happened,” he said. “We will find the young men and punish those responsible.”

On December 4, 2018, in his first act of government, López Obrador created by decree the Commission for Truth and Access to Justice in the Ayotzinapa Case (COVAJ) and ordered all state institutions to hand over any documentation they had on the disappearance of the students. The UEILCA was created almost seven months later, on June 26, 2019, by an agreement of Attorney General Gertz.

The Prosecutor

His brothers called him “the mute.” Omar Gómez Trejo says he was very withdrawn and quiet. He kept his hair long and always wore a baseball cap and jacket, a sport he played since he was a child. He liked ska and playing José José songs on his guitar. He spent entire days reading Fernando del Paso, José Saramago, and Antonio Tabucchi. He argued with his PRIista father. He believed in the rule of law.

He studied law at the Higher Studies Faculty, Acatlán, part of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), and did his social service at an office of the Organization of American States. A year after graduating, in 2004, he completed a six-month internship at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in San José, Costa Rica. Back in Mexico, he studied for a master’s degree in human rights at the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences. He was then offered a job at the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Guatemala, and began living between there and Mexico.

About five days after the attacks in Iguala, Gómez Trejo’s boss at the UN offices in Mexico City asked him if he could go with a colleague as a human rights observer to interview family members and students. “I remember we came back with a lot of information from those first interviews. When we were on our way back from the school, my UN colleague was crying in the back of the car and I was crying in front. And the driver didn’t understand what was going on…. That moment of the return was very hard, very hard, because you realize that you are facing something very, very terrible.”

A month later, the then attorney general of Mexico, Jesús Murillo Karam, called the head of the OHCHR in Mexico and offered him a helicopter trip to observe the Cocula trash dump, where, he said, two students were found. Gómez Trejo and his UN colleague were also selected for this task. They each went home for a change of clothes and then to the Attorney General’s Office (which was then known as the PGR). They boarded the helicopter and were flown to a soccer field in Cocula, which had been converted into a base of operations for the PGR and the Secretariat of the Navy (SEMAR).

There they were asked to wait for the “boss,” who turned out to be Tomás Zerón de Lucio, director of the PGR’s Criminal Investigation Agency, who ordered them to be taken to the dump. “And then they put us in a van where there were two men armed with machine guns…. We were all cramped together.” Once in the dump, “the public prosecutors began to explain to us; down in the dump we could see how the experts were working. We stayed in the upper part.” The explanations were not clear: “I didn’t understand anything at all,” Gómez Trejo says.

Three months later, on January 27, 2015, Gómez Trejo was sitting in a neighborhood restaurant eating lunch with two colleagues from the UN. Murillo Karam and Zerón’s press conference was being broadcast on television. During that press conference they presented the “historical truth” of what happened in Iguala, based on videos of three alleged confessions. The investigations led to the conclusion, according to Murillo Karam, that the 43 students were killed and incinerated in the Cocula garbage dump by members of Guerreros Unidos, who then put the remains of their charred bones in plastic bags and threw them into the nearby San Juan River. A colleague who had a lot of experience documenting cases of torture, upon observing the videos of the detainees shown during the broadcast said: “Look, those guys look really worked over.”

While the state was constructing its supposed truth, the GIEI arrived in Mexico. Gómez Trejo knew two of its members: Guatemalan prosecutor Claudia Paz y Paz and Colombian lawyer Alejandro Valencia. It was the latter who sought him out to tell him that they needed to hire someone in Mexico to help them, and asked him if he was interested. “Yes, of course,” he replied. He then had an interview with another member of the group, the Basque doctor Carlos Beristain, who asked him to join immediately. From that day on he was the technical secretary of the GIEI.

The GIEI

I met Gómez Trejo at that time. One day in the spring of 2015 we traveled together to Iguala and Cocula with two other people. We went to conduct interviews with key witnesses in the Ayotzinapa caseme as a journalist, Gómez Trejo as the technical secretary of the GIEI. We talked to the two workers at the Cocula trash dump. They told us that they went to unload the garbage on Saturday, September 27, 2014. They went after noon because the road was wet due to the rain the night before. There was no one there. They did not see anything. They dumped the trash, and then they left. According to Murillo Karam and Zerón, hitmen were still incinerating the 43 students right there at that moment.

After that day, I only saw Gómez Trejo at GIEI press conferences and presentations of their reports. He continued to travel to Guerrero to conduct interviews and inspect sites. He participated in search expeditions; sometimes they would run into snakes, sometimes armed residents. Other times they were followed. When the GIEI met in his apartment, everyone put their cell phones in the refrigerator.

Just before the first anniversary of the attacks, in September 2015, the GIEI presented its first report. The document disproved, based on evidence, the PGR’s investigation. From that day on, the Mexican government began to close its doors to the group and hinder its work, while conducting a media campaign against it. Even so, the experts presented a second report six months later, which documented the participation of various state security forces in the disappearance of the students and the torture of the detainees.

The biggest revelation was a series of videos and photographs showing an operation by the PGR and the Navy, directed by Zerón, at the Cocula trash dump and the San Juan River, carried outaccording to the recording of a couple of independent journalists, verified in the metadata of their imageson October 28, 2014. The GIEI assured that there was not a single document of that operation in the case file. Government officials returned a day later, when they supposedly found a plastic bag with bone fragments, including a single charred piece of bone belonging to the Ayotzinapa student Alexander Mora Venancio. What were they doing there the day before and why didn’t they document their actions, as required by law?

On October 30, Zerón showed his own videos at a press conference. He pointed to the moment when Gómez Trejo and his UN colleague arrived in Cocula as observers. He paused the recording and emphasized the fact that Gómez Trejo, working with the UN in 2014, was then the technical secretary of the GIEI.

Showing their faces and writing their full names on the screen, Zerón sent a double message. One was direct: the government did nothing wrong, even the UN observed us. And the other was indirect: we have you in our sights, Mr. Technical Secretary of the GIEI. Because it was a pantomime. The PGR tortured the detainees, nobody was incinerated in the Cocula trash dump that September night, they planted the bone fragment of Alexander Mora Venancio in the San Juan River. It was all a set-up.

And although they did not know it at the time, the government had already infected the cell phones of the members of the GIEI, Gómez Trejo, journalists, and lawyers for the families of the 43 disappeared students with the Israeli spyware program, Pegasus.

“Yes, it scared me,” Gómez Trejo tells me when I ask him about that time. “Because there were people who I later found out worked with Tomas Zerón who approached me. And then there was a day when they came to my house: ‘Oh, what’s up, boss?’ Is this where you live?’ And that’s when I understood that I had to distance myself. So, I had to leave Mexico to avoid, well… whatever. I mean, those people were really powerful at that time.”

The government refused to renew the agreement with the GIEI, removing the group of experts from the case and the country in April 2016, days after the presentation of its second report. Gómez Trejo left Mexico with Chilean lawyer and GIEI member Francisco Cox on a flight to Santiago, Chile. He carried two suitcases. “It was hard,” he says. “There was a sense of guilt, you know? Why do I have to leave Mexico? We did good. We did good work.” From Chile he traveled to Guatemala, then to Washington, then on to New York, where he lived for a month in a hostel, wandering the streets of Manhattan until the UN offered him a job again at OHCHR, but this time in Honduras.

At the time, Juan Orlando Hernándezcurrently facing drug trafficking charges in the United Stateswas president. During his administration, Honduras had become the deadliest country for land and environmental defenders. On March 2, 2016, a commando in the service of a former military officer and businessman killed Indigenous defender Berta Cáceres in her home. Gómez Trejo was tasked with investigating her murder.

“So, Honduras turned out to be a disaster because of all the emotional weight of what Ayotzinapa represented,” he says. He resigned after a year with the idea of returning to Mexico and looking for a job as a waiter on the beach.

One day, as he was preparing to return, James Cavallaro, a law professor and former president of the IACHR, called him. He was in Honduras. They went to dinner and Cavallaro told him to go to Washington because the IACHR needed someone knowledgeable about the Ayotzinapa case to move forward with the follow-up mechanism it had negotiated with the Mexican government after it decided not to extend the mandate of the GIEI.

Gómez Trejo went to Washington to work for the Special Follow-up Mechanism for the Ayotzinapa Case (MESA). His work consisted of studying the case file, mainly the more than 400 volumes that had been added after the group of experts had departed.

“I was never allowed to travel from the United States to Mexico,” during that time, he says, “because apparently there was a request by someone from the Mexican state that I be prohibited from traveling to the country. They negotiated that with the executive secretary of the Inter-American Commission.”

With the change of government when López Obrador entered office, the situation changed. Gómez Trejo returned to Mexico in March 2019. The return was difficult: “The first few days I was scared shitless. I wouldn’t even leave the house. It’s just that all those who were [involved in the torture and manipulations in the PGR] in 2016, when I left, all of them were still in there.” (The PGR changed its name to the Fiscalía General de la República, FGR, in December 2018.)

Human rights defenders Ana Paula Hernández and Abel Barrera convinced him to apply for the position of special prosecutor for the Ayotzinapa case. At the time, the government was drafting the agreement that would establish the UEILCA. Gómez Trejo’s friends told him that he knew the case file like few others. He called the lawyer for the families of the disappeared students, Santiago Aguirre, to consult with him and ask him to discuss it with the fathers and mothers. When they said they agreed, Aguirre sent Gómez Trejo’s résumé to Human Rights Undersecretary Alejandro Encinas.

Alejandro Gertz Manero, the attorney general, interviewed him. Gertz asked him: “Why hasn’t the case been solved? What do you think is the main motive for the disappearance of these students? And how old are you, brother?” Noting how young Gómez Trejo was, then 39 years old, he said: “I was already a prosecutor. I was a public prosecutor when you were not even born yet. Imagine that. We will be in touch with you. Thank you very much for the time you have taken. See you later.”

The interview for the position of special prosecutor in the most controversial case in Mexico in recent years lasted barely fifteen minutes. The following Monday he was summoned to take a “confidence exam” (similar to a background check), from 11 a.m. until 9 p.m., with no time to eat. The next day he was the special prosecutor on the case.

Time to Purge

And so, from one day to the next, Gómez Trejo went up to the 25th floor of the FGR, took the oath of office before the constitution, and went down to the office, where 70 people were waiting for him. Looking them in the face he thought: “Holy shit, what are we going to do?”

The first thing he did was interview everyone in the office. He made an initial assessment of who actually worked and who said things like: “You won’t be able to do anything, boss, this is tied up from above.” “Whoever they bring in is not going to make it.” “No, boss, I can’t come to work tomorrow, the thing is, I’m the godfather of a quinceañera and it’s far away. I’m going to take my whole family. If you want, I’ll invite you. You should come along.”

One day, he recalls, “they had prepared a document for me with all the torture investigations and it was on my desk. One of those old public prosecutors who play dirty, who charge money for cases, and so on, came in and stole it from me. He put his documents on top of it and then picked it up, he took everything to his desk. I saw it. I went downstairs to look at the cameras, I saw when he left my office with my documents. I went to his desk and there were my documents.”

He asked for an internal proceeding to be filed and the thief’s superior told him: “I can’t do anything, boss. I trust him. He is my friend.” Gómez Trejo fired them both. To say that he fired them is a figure of speech, because in the world of the FGR you can’t fire certain people from the institution, you can only move them from one part to another. And while Gómez Trejo was investigating and trying to respond to the document theft, another official arrived on the sly to make copies of that same document.

“So that’s when I started firing people. I started to purge,” he says. “Every month I would take advantage and send five people out, 10 out. I let a lot of people go. The most important purge I did was in January 2020. On the last day of December, 15 to 20 staff members stopped working with me.”

While he worked on purging the team and firing officials, he gathered trusted collaborators and added young people like Damián, a pseudonym, an Agatha Christie-reading lawyer who knew about the Ayotzinapa case because he too had worked with the GIEI.

“We were like an oasis in the middle of the desert, in an institution with an archaic culture: it was people from that same institution who participated in the criminal acts [of the Ayotzinapa case],” says Julio, also a pseudonym, who joined Gómez Trejo’s team and, at the time of our interview, continued to work at UEILCA. “We had a lot of freedom in our work in the unit before August 2022. There were certain limitations when it came to finding [in the investigation] a high commander or a public servant linked to a renowned [state] organization. Many public servants from many spheres participated [in the tortures and lies], high-ranking officials who had not been prosecuted before. The director [Gómez Trejo] was very involved in the work of the investigation. We worked freely, but with a steady pace. We wanted to doing things right.”

Why are there three different agencies investigating the same case? What is each one’s role? The UEILCA is the specialized unit for the investigation and prosecution of the Ayotzinapa case that works within the FGR. Legally, it must have absolute independence. It is the only body with the legal power and authority to investigate, gather evidence, detain, bring the case before a judge, and present evidence against people involved in the disappearance of the students and crimes related to the cover-up, such as torture. The GIEI is a group of independent experts who provided technical assistance from March 2015 to April 2016 to the PGR, and then to the FGR from March 2020 to July 2023. The COVAJ is the strangest of the triad. Its name says it is a truth commission. According to Aguirre, one of the legal architects who designed it, it was created to give legal legitimacy to Encinas’s political work.

“The idea arose that there should be a presidential decree that would create a commission headed by Encinas so that it would have legal powers,” Aguirre tells me. “Not as a truth commission like the traditional ones that have existed in Latin America, which have the main task of producing a clarifying report, but as a mechanism that would remove the political obstacles in the case.”

The three agencies would work together, each with its own role, to investigate, gather, and share information to solve the case and pursue justice. That was the plan. It did not happen that way.

The agreement that created the UEILCA orders it to bring together all the legal cases related to the disappearance of the 43 students. This was one of the recommendations of the GIEI since 2015 and one of the requests of the families. Once the UEILCA’s work got underway, all the investigation files related to the events of September 26 and 27, and to the crimes committed by public officials during the “investigation” of the Peña Nieto government, began to arrive at the unit. Gómez Trejo ordered the creation of two teams: group A for the September 26-27, 2014 attacks and group B for the cover-up.

All of the charges in the PGR’s Ayotzinapa case were for kidnapping or homicide. At the UEILCA, Gómez Trejo and his team changed the classification of the crime against the 43 students to forced disappearance. “It was one of the first things we did: reclassify the crimes, re-orient the investigations, reorient the cases.”

Don’t miss Part II and Part III of this investigation.

John Gibler is the author of four nonfiction books about politics in Mexico including I Couldn’t Even Imagine that They Would Kill Us: An Oral History of the Attacks Against the Students of Ayotzinapa (City Lights, 2017).

The author would like to thank Global Exchange for support for research and translation.