This is an excerpt from Translating Blackness: Latinx Colonialities in Global Perspective. Copyright Duke University Press, 2022.

After the execution of dictator Rafael Leónidas Trujillo in 1961, a revolutionary energy manifested in every demographic of the population. Farmers began to organize to reclaim land ownership, migration to the city and to the United States increased as a form of economic mobility for the poor, and the youthboth working and middle classbegan to organize politically through community-based organizations and formal political parties. The youth struggle, as Efraín Sánchez, leader of the Movimiento Popular Dominicano (MPD, Dominican Popular Movement), explains, took place in two arenas: poor and working-class neighborhoods and universities.

“We were concerned with access to basic human dignity, which had been denied to us for so long,” Sánchez tells me of 1960s working-class youth organizing. “With workers’ rights and the participation of working people in the political processes.”

For young, middle-class Dominicans, the fight was both political and ideological. Organizing within The Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo (La UASD), young Dominicans read Marxist theory together while envisioning a national project very much inspired by the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. A student activist I will call Mariam Almonte, from Villa Altagracia, remembers those early days as a sort of political awakening for the youth in her barrio.

“I went into the student meetings with my eyes shut and came out with them open,” she says. “We were reading Marx and seeing our country as a battleground and his work as a manual No one was in school just to studywe were there to fight for the future of a country we were all hoping to create post-Trujillo. We felt the country was a canvas and we had the brushes in our hands.“

In 1962, thanks in great part to the work of young activists and students like Almonte and Sánchez, the revolutionary energy of the moment led to the election of social democratic leader, politician, and writer Juan Bosch as president of the Dominican Republic. Bosch had been in exile since 1942 due to his opposition to the Trujillo dictatorship. During his two decades in exile, Bosch created the Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (PRD, Dominican Revolutionary Party) and orchestrated strong political resistance against the regime. Bosch’s social democratic agenda garnered immense popular support, and he won the election with an overwhelming majority.

The military and the Catholic Church, however, opposed Bosch’s agenda, which included labor unions and socialist reforms in education, health care, and other services. On September 25, 1963, after only seven months in office, a U.S.-supported coup led by Colonel Elías Wessin y Wessin overthrew Bosch. A three-man military junta then replaced the Dominican Republic’s first democratically elected government of the 20th century. The coup prompted a lot of anger and frustration among the general population and activated unprecedented participation in political activism, culminating in a civil war in 1965.

“They tore away our democracy,” Sánchez recalls.

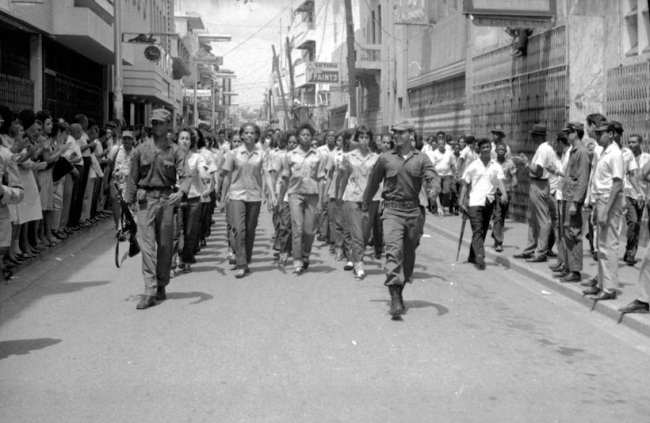

Known as La Guerra de Abril, the civil war that took place between April 24 and September 3, 1965, began when a group of deserted soldiers, along with civilian PRD supporters, seized the Radio Santo Domingo building, issuing calls of sedition and branding themselves “constitucionalistas” (supporters of the constitution). Their goal was to restore Bosch. During the first days of the conflict, constitucionalistas distributed weapons and Molotov cocktails to their civilian comrades who poured into the city from all over the country to join the effort. After only four days of battle, and what looked like a clear victory for Bosch, on April 29, U.S. president Lyndon Johnson authorized a large-scale military intervention aimed at preventing the development of what he saw as a potential second Cuban Revolution.

Perhaps because of the overwhelming support it sustained among the peasantry and leftist intellectuals alike, or perhaps because it opens the wound of the democratic republic that could have been and never was, La Guerra de Abril is one of the most studied Dominican events of the 20th century. In 2015 a transnational commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the war was organized by the Dominican state. It included photographic exhibits, publications, public events, and the formal recognition of multiple people in a ceremony held at the national palace. Aside from a handful of mostly middle-class women, all published photographs, books, and public consecrations of the heroes of the 1965 war are of and about men. Yet feminist scholarship, feminist testimonies, collective memory, and the testimonies of revolutionary women gathered by journalist Margarita Cordero in the late 1970s all demonstrate that the 1965 war would not have been possible had it not been for the women who risked their lives transporting weapons, serving as messengers, tricking U.S. Marines, and engaging in combat.

“We women were the ones who sustained the constitutional areas of the revolution in every sense of the word,” Cordero explained to me. “We were the ones who took care of the wounded, the ones who prepared the food, and the ones who made love with the combatants….Many of us did not fight in active combat, we were not exceptional, but what we did was valuable for the War.”

Cordero was a member of the Juventud Estudiantil del Catorce de Junio, 14J, or “Jecajú,” the student arm of the communist Catorce de Junio party. She was at La UASD in a meeting with fellow students on April 24 when the news of the revolution first reached her. Over the course of a few hours, as the revolution gained force, the different political sectors united. The predominantly middle-class communist party, Catorce de Junio, joined the revolution by the evening of April 25 under the direction of General Rafael “Fafa” Taveras.

The participation of middle-class women in the days that followed was significant for the organization of the movement and for the coordination of military actions. Women communicated with the different commandos through messengers and took over the quotidian tasks of care for wounded soldiers. “Women were the backbone of this revolution,” Taveras told me in an interview. “Without them, there is no Guerra de Abril.”

However, middle-class women did not, contrary to what some historians have argued, participate in active combat. Rather, the women who fought and died on the front lines were working-class and poor women from the neighborhoods on the outskirts, better known as La Parte Alta. In early May, many of these womenmost of them Black and Brownwere killed during the U.S. Marine-supported “Operación Limpieza” (Operation Cleanup).

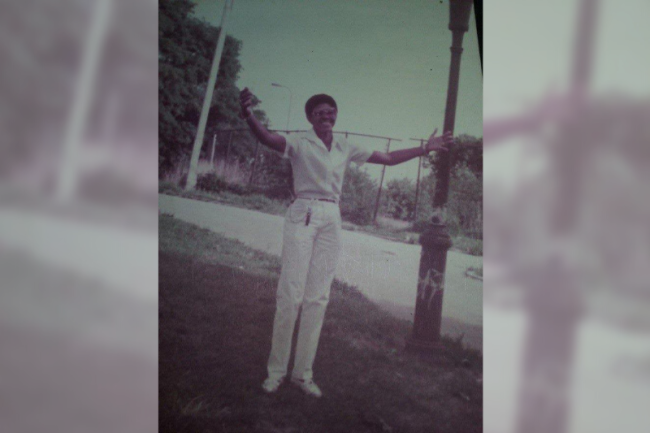

Yolanda, a 76-year-old Afro-Dominicana who now resides in Italy, lived in 1965 in La Parte Alta’s iconic Ensanche Luperón, one of the main battle sites of the U.S. military intervention. Yolanda participated in La Batalla del Puente Duarte on April 27, in which the constitucionalistas overthrew the military and essentially won the war prior to the intervention. She continued to serve the constitucionalistas, working as a messenger and spy in the weeks that followed the intervention. Yolanda recalls the day Operación Limpieza reached her neighborhood as a “brute” massacre that destroyed the bodies and morale of many working people.

“I was with the people, you know. With the revolution .I would go to the American military and wash their clothes and I would collect food and cigarettes and steal bullets from them and bring them down there to the boys who were hiding,” she explains.

“But then the cleansing’ happened, and it was a massacre, a brutality….The persecution did not end with the revolution, no sir. I never felt at peace again in the country. They were always after us. Then came Balaguer and all that nonsense continued. It wasn’t until I left for Italy that I had peace from that.”

Despite their contributions, the majority of working-class Afro-Dominicanas like Yolanda have been relegated to obscurity by a male-dominated archive that is more comfortable with the mythification of a handful of light-skinned middle-class women than with acknowledging the tangible and essential roles of many Black and Brown working-class Dominicanas.

“The War birthed many myths about women,” Cordero argues. “But these pictures you see with women holding weapons on their shoulders, riding tanks…are selfies .The women who participated in combat were not the militant Left….It was the women from La Parte Alta…Those women actually fought in battle.”

One of these “selfies” is the iconic image of Tina Bazuca. The famous photo depicts a smiling, light-skinned teenage girl holding a rifle in her right hand and a pair of sunglasses in her left. The caption for the photo, as well as the narrative around its subject, describes her as an “exceptional 16-year-old girl, who one day joined the revolution.” The photo, which has also become the logo for the highly profitable Tina Bazuca beer made by the artisanal República Brewery, shows the teenager wearing a skirt and sandals, seemingly not at all preoccupied with the war she was supposedly fighting.

The image, which has become emblematic of La Guerra de Abril, is a misrepresentation. The girl in the photo is, in fact, Julia Cabral Carezzano, a light-skinned upper-middle-class Dominicana whose brother fought in the revolution. Cabral Carezzano posed with her brother’s rifle but was not actually involved in the revolution.

But Tina Bazuca did exist. The real “Tina” was 28-year-old Augustina Rivas, a rayana from Dajabón. Rivas was born on May 13, 1937, a few days after Trujillo ordered the Parsley Massacre that killed more than 20,000 people in her hometown. In 1954 she moved with her family to the city in search of work. They lived first in Santiago and later in the Villa Consuelo barrio in Santo Domingo, most likely to work on the many construction projects of Ciudad Trujillo. Those who knew her describe Rivas as a “mari-macha” (tomboy/butch) with a hot temper and a real preoccupation with justice. She was a fighter for workers’ rights and an active member of the Sindicato de Trabajadores Portuarios de Arrimo (POASI) dockworkers’ union. She worked all kinds of jobs not traditionally considered feminine, including security guard and dockworker. During her free time, she volunteered as a boxing coach for children and teenagers and was an active member of her neighborhood workers’ organization.

When the revolution began, Rivas joined the constitucionalistas, immediately standing out among the women due to her superb combat abilities. Sánchez, who served in the same military commando as Rivas, remembers her as the most skilled of the guerrilla fighters: “She was so good they had her training men.” It was because of her uncanny abilities as a sniper that Rivas earned the nickname “Tina Bazuca.”

Stories about Tina Bazuca spread like wildfire among the women of the revolution. Yolanda, who never met her, remembers, “We all knew her even though we didn’t know her….She was a legend.”

After the revolution, Rivas continued to work for workers’ rights with POASI. However, facing persecution during Balaguer’s Terrible Twelve Years, she migrated by raft to Puerto Rico in 1976. Unlike Yolanda and other Dominican women veterans who found refuge in the social democratic environment of 1980s Italy, Rivas was quickly deported from Puerto Rico back to Santo Domingo. After multiple subsequent attempts to migrate and establish herself in the U.S. diaspora, in 1991 Rivas was forced to return to Santo Domingo, where she struggled to find work and support herself and her daughter. Five years later, she died of a massive heart attack at age 59.

Of the multiple testimonies and stories about La Guerra de Abril that have been entrusted to me over the years, Tina Bazuca’s is the most remarkable. She lived an extraordinary life against death from birth, yet her extraordinary life has been obscured by a fictionalized image that mimics and reproduces Dominican colonial desire for whiteness. What does it mean for Dominicans to remember “Tina Bazuca” but not know who she actually was? How do we grapple with the fact that the extraordinary life and contributions of an Afro-Dominicana are only remembered through an invented story about a posed photo of a young light-skinned girl? That the Cabral Carezzano photo has been celebrated and commercialized while the real Tina Bazuca experienced persecution, migration, deportation, hunger, and violence tells us a lot about the Dominican state valuationor lack thereofof Black women’s lives. It exemplifies the gender-based violence through which Black Dominicanas’ deeds and bodies are appropriated and performed through whitewashed representations that are more acceptable to the public. It illuminates Dominican colonial desire for whiteness at the expense of Black lives.

Since the foundation of the Dominican nation, myths about white Dominican women have fueled patriotism and a nationalist agenda at the expense of Black and Brown Dominican women. In the 19th century, the image of the white Dominican virgin in need of protection fueled anti-Haitianism and plagued national rhetoric. After the fall of Trujillo in 1961, Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa Mirabal, who were brutally murdered in 1960 as a result of their political work against the regime, became symbols of a new patria in which women could become political actorsthrough men’s protection. The death of the Mirabal sisters, three light-skinned upper-class women from the Cibao region, is often invoked as the single most traumatic event of the Trujillo regime, even when compared to the genocide of more than 20,000 ethnic Haitians and Afro-Dominicans in Dajabón, the execution of dozens of political dissidents, and the rape and torture of hundreds of women and girls.

I do not want to diminish the significance of the Mirabal sisters, either in their political work against the Trujillo regime or as symbols of the struggle to end violence against women. Rather, I want to call attention to the “other women” who are erased from the history of the very nation they helped build: women like Yolanda, who have taken their fight against death to the diaspora precisely because, as she put it, “if I did not leave, I would be dead.” We must unsilence these womenpoor, Black, Brown, rayana, migrant, trans, queerin the archives. We need to say their names.

This excerpt has been lightly edited for length and style. For figures, endnotes, and quotes in Spanish, see the original: Chapter 3 “Against Death: Black Latina Rebellion in Diasporic Community,” pp. 121-131, in Translating Blackness: Latinx Colonialities in Global Perspective (Duke University Press, 2022). Excerpt reprinted with permission.

Lorgia García Peña is a scholar of Latinx Studies in the Department of Studies in Race, Colonialism and Diaspora at Tufts University and the co-founder of Freedom University. She is the author of Community as Rebellion and the internationally acclaimed The Borders of Dominicanidad: Race, Nation and Archives of Contradictions.