This piece appeared in the Summer 2022 issue of NACLA’s quarterly print magazine, the NACLA Report. Subscribe in print today!

Leia este artigo em português. Translated to English by Joyce Silva Fernandes.

Black people make up the majority in Brazil. Over half of the nation’s 215 million inhabitants56 percent or about 120 million peopleare Afro-Brazilian, making the country home to the largest Black population in the Americas. As a result, analysis of all political, economic, societal, and cultural matters in Brazil must consider racial issuesor rather, issues of racial inequalityas a central axis.

For generations, a consensus reigned in both the academy and public opinion that Brazil’s leading problem was the problem of class inequality. The Right and the Left shared this perspective, refusing to recognize and confront racial inequities. The myth of racial democracythe national narrative of harmony between races and the idea that racial mixing offered prime evidence of the absence of racial hostilitiesserved to defend these beliefs.

However, from the 1990s onwards, new studies seeking evidence-based understandings of race relations in Brazil began to question the thesis of a country, always positioned in contrast with the United States, where harmonious and egalitarian race relations flourished. Images deployed to promote tourism abroad featured smiling Afro-Brazilians having funcaricatures that presented a carnivalesque representation of a country whose underlying inequalities could not be understood without analyzing and comparing the lives of Blacks and whites.

Indeed, in the social imagination and across the spheres of health care, politics, employment, and, above all, education and housing, two distinct Brazils are observable. One is a country of privileged people, while the other is a country of people whose lives are marked by poverty, the absence of multiple rights, and personal experiences of violent and traumatic events motivated by racial hatred.

For Black people, the data emerging from research in the 1990s and 2000s did not reveal anything new. Black social movements and popular organizations, many of them led by women, and Black workers’ collectives had been denouncing racism as the leading cause of the country’s racial inequities since the late 1960s and 1970s, then in a context of military dictatorship. With a critique of fictitious racial democracy, the Black movement interpreted the Black population’s life conditions as a consequence of the lack of a politics of inclusion and guarantees of citizenship, which remained absent after Brazil finally abolished slavery on May 13, 1888.

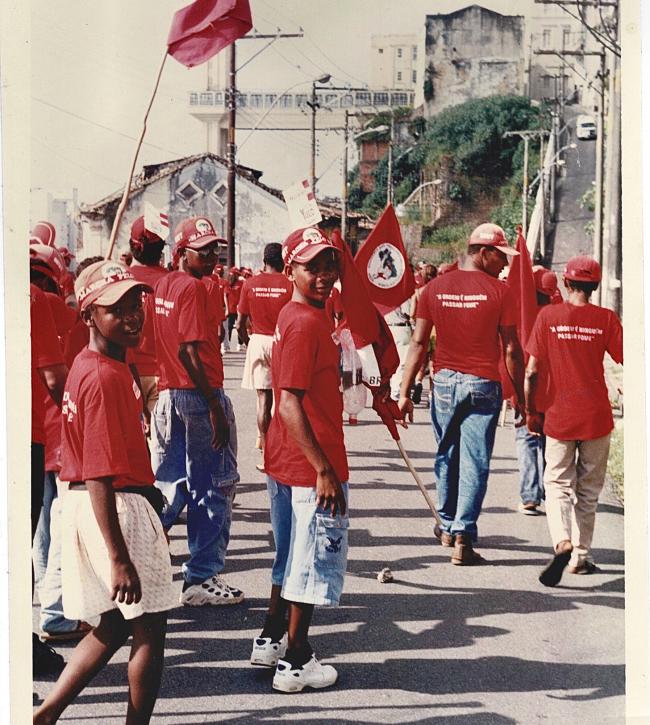

The photograph included here highlights an important moment for Black movements within the broader context of left-wing struggles in Brazil. In it, a group of Black adults and children dressed in red, a color associated with leftist social movements, march in the city of Salvador, the largest Black city in the Americas. It is a demonstration of the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) around the year 2002. As they walk, boys look back innocently, as if signaling what the future will bring for those who fight for their rights. The backs of their shirts read: “Order means no one going hungry.”

When a workerformer trade union leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of the Workers’ Party (PT)was elected president in 2002, his victory was also the result of Black movements’ engagement and mobilization. Black movements helped build Lula’s political project by putting forth policy proposals that concerned the Black population. Though far from precipitating the end of racism in Brazil, the participation of Black leaders in government promoted deep changes in society, particularly through the expansion of rights. The recognition of domestic workers’ labor rights and the adoption of affirmative action policies benefiting Black students in universities were among the most important advances.

On the eve of Brazil’s general elections later this year, this issue of the NACLA Report seeks to view contemporary Brazil through this racial justice lens and to discuss crucial issues debated in social movements, the public sphere, and universities that have guided the course of national politics.

Pitting the far right, embodied by current president Jair Bolsonaro, against the diverse coalitions rallying behind Lula’s candidacy, the October presidential election represents the possible return of the Left to power. More than a battle between two political parties, this election offers Brazil a choice for a new political, ideological, and civilizational path. Depending on the outcome of the vote, the country may cement its distance from the minimal parameters of a democracy. Or, conversely, Brazilian society may return to a democratic world where actions are guided by adherence to the constitution, consideration of the recommendations made by international health authorities, and, above all, respect for human rights.

The articles in this Report reflect this quite peculiar moment in Brazilian politics, particularly as experienced by Black people. It has been precisely during a right-wing conservative government, which rose to power promising to strip the most vulnerable social groups of their rights, that Brazil suffered the impacts of a pandemic that pushed it to see one of the highest Covid-19 mortality rates in the world and a total number of Covid-related deaths second only to the United States.

Like in the United States, Black people in Brazil died of Covid-19 at disproportionate rates, and in many cases, they were the first ones to contract the virus. Real-life stories of some of the first victims of Covid-19 in Brazil put this reality into stark relief: a doorman in São Paulo; a domestic worker in Rio de Janeiro, infected while taking care of her employers who had just arrived home from Italy; another domestic worker in Bahia, whose employer’s family had also just arrived from Europe. In addition to Black people, those who depend on the public health system were overrepresented among those who died of Covid-19.

The pandemic deepened already poor working conditions and increased unemployment, which disproportionately affects Black people. Brazil got back on the world map of hunger, and public schools showed an increase in the number of students who abandoned their studies, plunging the country into a 20-year educational setback. Femicide increased, as did child sexual abuse, and police actions in communities continued killing Black people en masse, particularly Black youth. These incidents further exposed the problems of police violence and Black genocide as a consequence of the war on drugs. Denialism was also widespread, and the administration’s disregard for the severity of the pandemic, combined with rampant disinformation and fake news, discouraged and delayed a broad vaccination program. These and other negative consequences stemmed from the government’s incompetence and negligence in the fields of health care, education, and public safety. Ultimately, research has shown that the impacts of these policies and increased inequalities are most felt by those of a specific race and gender: they are Black people, mainly women and their children.

The articles in this issue aim to offer a record of this moment for the Black diaspora and beyond: they are reflections and analyses written by experts, activists, and scholars in fields such as health, public policy, and LGBTQI+ rights, and by people concerned with the genocide and imprisonment of the Black population. The pieces also deal with how Black social movements, Black women’s movements, intellectuals engaged in anti-racist struggles, and Indigenous populations have articulated and organized themselveswhether through art or mobilizationto respond to genocidal policies and claim space in politics. Particularly in the wake of the assassination of Black activist and politician Marielle Franco in 2018, key debates have emerged or deepened regarding whiteness in the academy, affirmative action in universities, and the creation of projects to archive the Black memories long preserved in traditional communities and urban Black cultural productions.

Taken together, this NACLA Report attempts to highlight the effects of racism, sexism, patriarchy, and exclusionary policies on Afro-Brazilian populations. Attention to these issues is urgent as an authoritarian government deploys anti-democratic experiments, suppresses rights, and exacts violence on Black bodies as a means to demonstrate its power. With fascism on the rise globally and Brazilian democracy in agony, the world will turn its gaze this year toward the country’s general elections. In this context, our goal is to showcase how Black people in this corner of the diaspora resist, organize, and stay alive, developing diverse strategies for survival and well-being in the process.

Axé.

Luciana Brito holds a doctorate in history and is professor at the Federal University of Recôncavo da Bahia in Brazil.

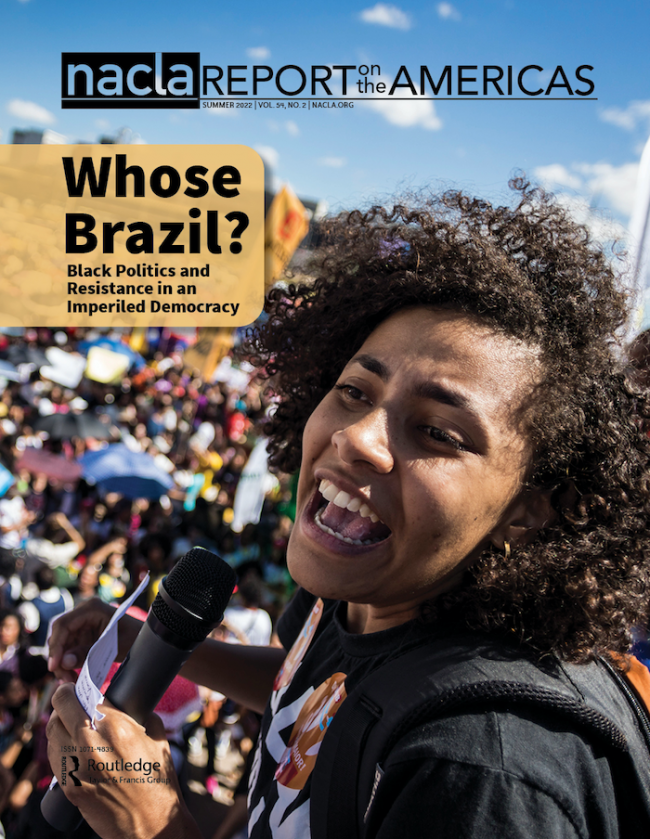

Cover photo: A protest in defense of public education and against President Jair Bolsonaro’s policies, Brasília, May 30, 2019. (Mídia Ninja / CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)