Leer este artículo en Español.

Perhaps the hardest part is not leaving, but knowing you won’t be free to return.

In May of 2022 I fled Manizales, three months into my gender transition. Public and private spaces had become uninhabitable. After 12 years of local LGBTIQ+ activism, the visibility of my transition was the perfect excuse for me to stop being a mere object of finger-pointing and become instead the target of public scorn, invasive practices, questioning about my gender identity, and other forms of discrimination.

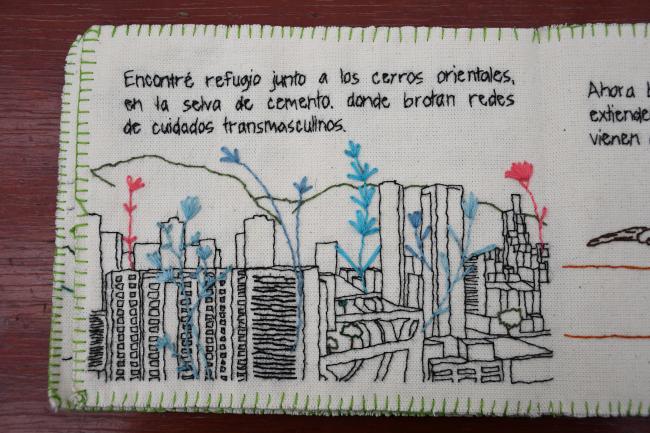

At the first opportunity I packed my things and fled, holding onto the hope that someday I would be free to return to live in my hometown. However, traveling periodically from Bogotá to Manizales, in Colombia’s coffee belt, became a way of traveling through time. Geographical borders became time portals; some loved ones remained nostalgic about a past completely distant from my present, and the transphobia rooted in the city became unbreathable.

I had been living in Bogotá for almost two years, feeling like a passing traveler awaiting his return to his place of origin. But in April 2024, in the middle of a trip to Manizales, I realized definitely that I would never be free to return. I surprised myself with this unattended pink elephant in the room of my life, left unattended for too long. It was an unresolved pain that for two years I had refused to face: migratory grief.

Politicizing Wounds through Research-Creation

Finding myself hopelessly confronted with the fact that I was no longer a visitor in Bogotá but a resident, and that to the contrary I had become a visitor in my own town, I decided to seek out Valentino, a lawyer, activist with the organization Transgarte, and a trans man. Valentino had also had to abandon his place of origin due to discrimination and faced multiple hostilities every time he returned to visit his loved ones in Puerto Colombia, on the Caribbean coast.

I proposed to him that we embark on an academic-activist exercise of research-creation, in which we would explore our experiences of internal migration and forced displacement to Bogotá. I proposed that we meet regularly to build an open dialogue in which he would also ask me questions, disrupting the researcher-researched binary logic and alternating between both possibilities. To avoid falling into dynamics of epistemic extractivism, I proposed an exchange that he accepted: Valentino would use our conversations to make a series of podcasts for his organization Transgarte, and I would produce a textile book with our stories. For the first time in my life, I was not the one who recorded the interviews and asked the questions.

Over the following weeks I devoted a great deal of energy to finding a concept that would allow us to put our experiences in dialogue. However, each day I found more differences than similarities. Valentino was forcibly displaced from Puerto Colombia due to the police and community harassment he suffered because of his gender identity and activism, endangering the safety and integrity of his life and his organization. On the other hand, I experienced a process of internal migration motivated by family, social, and community discrimination. This exodus was triggered by my transition to masculinity and exacerbated by the visibility of my activism in the territory.

In the midst of this search, I ended up writing about the grief of destierro, or expulsion from the land. Those words resonated with Valentino, who told me that they reminded him in particular of a poetic image of “the sea retreating, leaving behind wet and cracked mud.” To graphically explain this reference, he sent me an image of the Aral Sea in Qatar. My head exploded. That’s when I understood that what had been taken from Valentino was the sea, not the mountains.

While I had been uprooted from the land—destierro, Valentino had been uprooted from the sea—desmar.

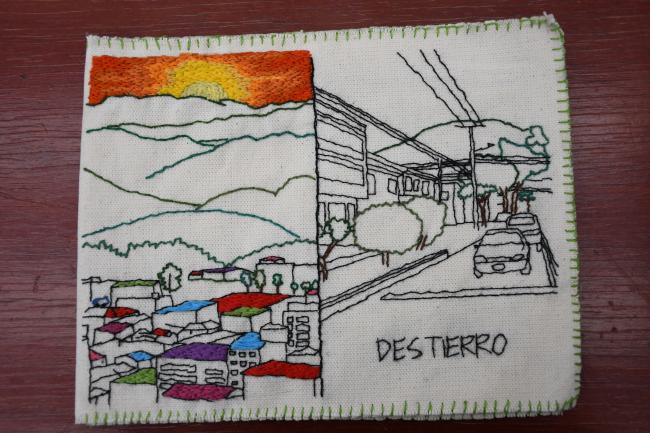

What seemed like a new bifurcation in our quest turned into an opportunity for creation. So I decided that I would make two embroidered books instead of one: Valentino’s would be called Desmar, and mine, Destierro. From this epistemic-textile twist I ventured into a universe that until then I had not known: the digital drawing board, a device that for years I had observed in other hands, now emerged as a key tool to visually represent our maritime and mountain trajectories and guide the embroidery process.

Geographies of Expulsion: “Small Town, Big Hell”

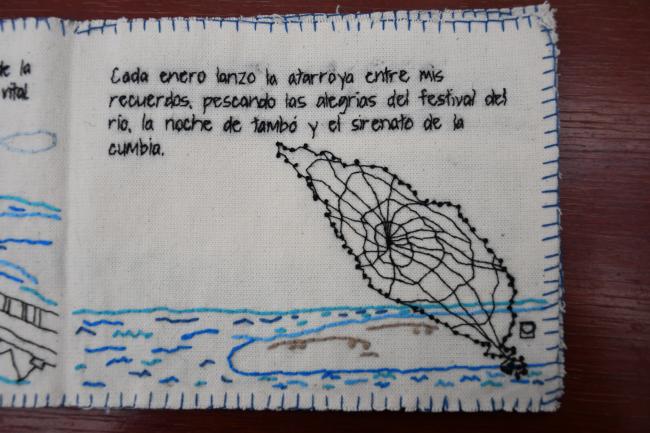

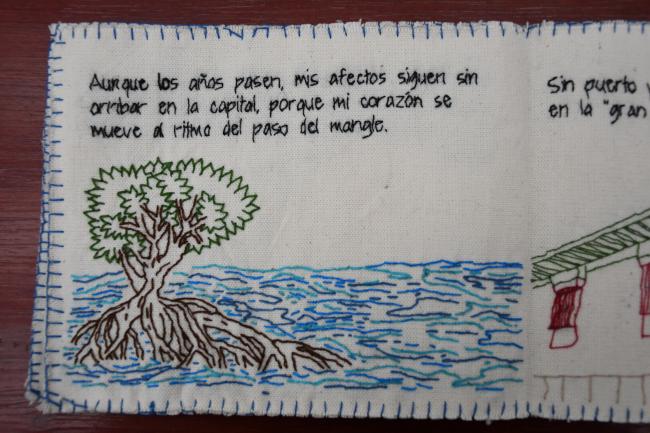

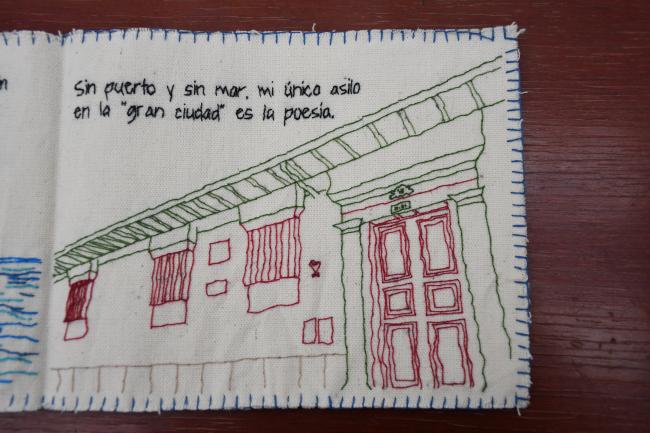

For desmar I drew a photograph taken by Valentino of a fisherman’s landing and a drawing he made from a memory he had of the port. In another fragment, I represented the fishing net with which Valentino learned to fish, the red mangroves typical of Puerto Colombia, and the Casa de Poesía Silva in Bogotá, a cultural center where Valentino has had the opportunity to find refuge in the written word.

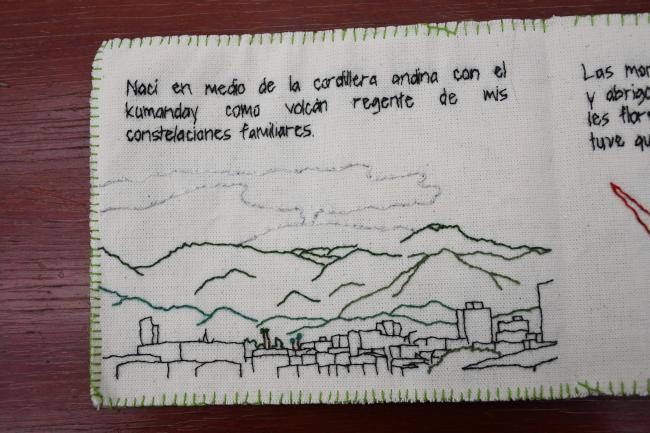

For destierro, I drew on different photographs of the mountains where I had walked, the longed-for natural landscapes that contrast with the cement that pulses through the city. Between lines, strokes, dialogues, readings, and embroideries, I began to find common threads between our trajectories: the paramilitarized culture, the deep-rooted religiosity, and the small geography of our places of origin.

Puerto Colombia is a municipality in the Caribbean region of Colombia located in the northeastern part of the Atlántico department, where the armed group “Clan del Golfo” operates, and whose main religious symbol is el Santuario Mariano Nuestra Señora del Carmen (Our Mary of Carmen Sanctuary), which holds annual festivities that draw many visitors to the territory.

Manizales is located in Colombia’s Andean region and is the capital city of the department of Caldas, which includes La Cordillera range and an extensive network of religious landmarks that cross the entire municipality. The most prominent is la Catedral Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Our Lady of the Rosary Cathedral Basilica), a tourist attraction because it is the tallest cathedral in the country.

Both territories share conservative religious characteristics and the presence of armed groups founded by former paramilitary leaders—Vicente Castaño and Don Mario of the Gulf Clan, and “Macaco” in La Cordillera. The two regions are permeated by a paramilitarized culture of religious fundamentalisms tinged with transphobia, and a history of practices of social extermination perpetrated against social sectors that transgress the moral margins of what is considered socially acceptable. These socio-political characteristics make the perfect breeding ground for acts of stigmatization and violence that complicate the possibilities of continuing to live in these places for those who are transmasculine, activists, and recognized participants in social movements.

Both Puerto Colombia and Manizales are geographically small, which facilitates social discrimination, police profiling, and transphobic labor exclusion. They also tend to exhibit other discriminatory practices that oscillate between what the transmasculine researcher Nikita Dupuis-Vargas Latorre categorizes as processes of forced feminization and the punishment of transmasculinity. Thus, under different situations with common characteristics, both places end up triggering our respective flights to Bogotá, in search of the anonymity offered by a big city and the possibility to meet peers, join networks of transmasculine care, reestablish wellbeing, and identify other opportunities.

Embroidering the Punishment of Destierro and Desmar

After years of thinking with words, I learned to think with stitches, spinning ideas, unraveling emotions, joining fabrics, knotting reflections, cutting threads of violence, and interweaving resistances. Embroidery became the thread that connected ideas, territories, and experiences to understand the ways in which destierro and desmar are imposed as forms of punishment on transmasculine activists, materializing what researchers Francisco Romero Fernández and Marce Joan Butierrez call the spatial perspective of oppression.

The punishment of destierro and desmar are imposed at various levels and through various institutions including the family, the police, politics, labor, and the economy, undermining the possibilities for transmasculine activists to remain in our places of origin in a visible manner. The administration of these types of sanctions is facilitated in small towns and cities because the lower population density simplifies the processes of profiling, persecution, prosecution, and discrimination in different dimensions of life.

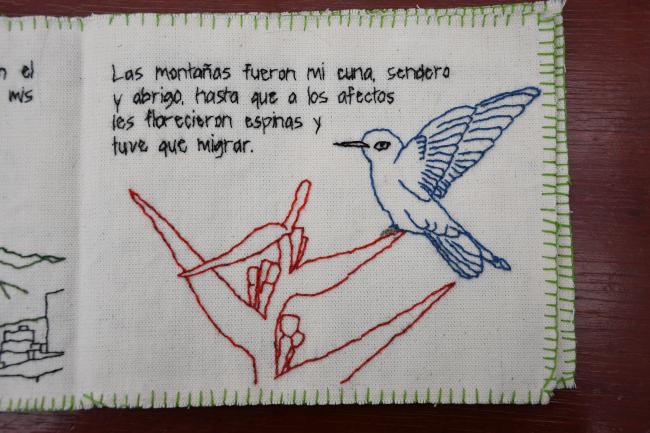

However, forced displacement and internal migration not only generate geographical distances from our places of birth. Destierro and desmar create profound ruptures with respect to daily practices and the ways we construct our gender identities anchored to the ecosystems in which we were born, turning Valentino into a fisherman who does not fish, and me into a mountaineer who does not traverse mountains. In other words, the visible and militant recognition of our gender identities as transmasculine ultimately stands in irreconcilable contradiction with the recognition of our identities in a territorialized and maritimized way.

On one occasion, I asked Valentino if he had contemplated the possibility of fishing in a lake in Bogotá. Without hesitation he told me no; he explained that while he had always used a net, in the interior of the country fishing is practiced mainly with a rod—a technique that for him does not compare with the experience of casting a net in the open sea.

On another occasion, some friends asked me how I had managed to tone my calves without practicing sports. That was when I understood that my body bore the traces of my territorial origin, reflecting the years I had spent walking and cycling up and down the hills of Manizales. I also understood that this was a physical imprint of my class origin, because if my parents had had a car I would not have walked so much through the hills of Manizales.

Nikita argues that transmasculinities in Bogotá are produced in orality. When we arrive in the capital we have to reinvent the ways in which we produce our transmasculinities, without fully rooting ourselves in the new territory. In Valentino’s case, the Casa de Poesía Silva has become a habitual place for him to make connections through poetry. In my case, transmasculine networks of care and affection have been the bridge that has allowed me to take root in Bogotá.

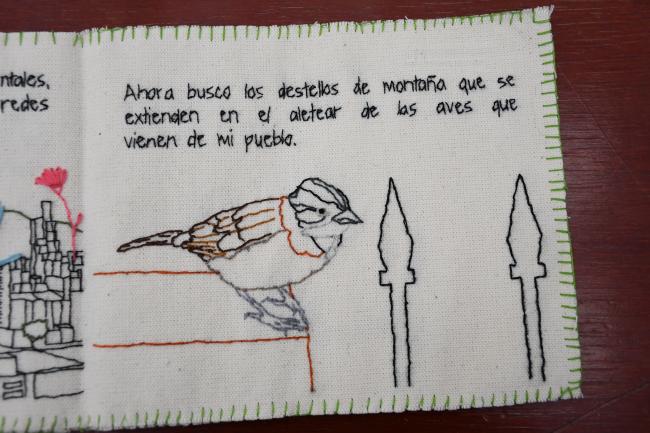

Although at this point the struggle of destierro seems to be a resolved issue, all it takes is for me to have to go to an unknown place in Bogotá to feel like “a villager in the big city” again. Whenever I go somewhere new, I give myself enough time to get lost and find myself again, because it is certain that I will get lost. Inevitably, even after three years in the capital, I still feel like an outsider.

Uno se va del pueblo pero el pueblo siempre se queda en el corazón. One may leave home, but home always remains in the heart.

Today, I live with the nostalgia of the lost landscape, like an eternal migrant who does not know if he will continue to live in Bogotá but who will not return to Manizales either. I have a point of departure, but I have no point of arrival. As the Egyptian poet Ahmad Mohsen says: “there is no road longer than flight.”

Morgan Londoño Marín is a sociologist, political embroidery apprentice, and the son of public education. His research focuses on violence, human rights, genocidal social practices, and gender.