Leer este artículo en español.

BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA. Chants and leaps extended into the night of April 23 in front of the Casa Rosada. “UBA defends itself,” “Why are you so afraid of educating el pueblo (the people)?”, “Milei, garbage, you are the dictatorship,” “The patria (homeland) is not for sale!”, repeated groups of people in front of the fences installed to block the way to Argentina’s government house.

The demonstrators waved flags and put up posters under the watchful eye of rows of police officers stationed in front of them, on the other side of the metal wall.

The energy of these groups of protesters did not appear to run out, even after hours of protesting in the streets of the city. They had taken part in one of the largest marches seen in recent years in the country, and the largest so far during President Javier Milei’s administration.

They came out to defend public university education and formed, together with thousands of others, an unprecedented tide of at least 800 thousand people.

They told Milei and his followers that they were there, and will continue to be there, to defend free and public university education.

Public Higher Education At Risk

At the beginning of April, alarm was raised about the risks that public university education was facing in Argentina. There was concern about whether or not Milei’s administration would maintain the budget extension allocated to public universities.

This extension does not take annual inflation into consideration, equivalent to a little more than 270 percent. Therefore, in practice, the budget for universities was reduced by 70 percent, according to the Asociación Civil por la Igualdad y la Justicia (Civil Association for Equality and Justice, ACIJ), quoted by elDiarioAR.

Already on April 5, Emiliano Yacobitti, vice-rector of the University of Buenos Aires (UBA)the most prestigious university in the country and one of the most important in Latin Americapointed out that the situation could reach its limit. Yacobitti warned that a large part of the university was going to “shut down during the second term” if Milei’s position did not change.

Milei has attacked public education on several occasions. As a presidential candidate, he proposed to eliminate mandatory education (primary and secondary). Last March during the IEFA Latam Forum (a meeting of businessmen within the energy sector), he said that public education “has done a lot of damage by brainwashing people.” He aimed his criticism specifically against UBA’s Faculty of Economic Sciences.

Tension continued to increase and on April 10, UBA’s Consejo Superior (Higher Council) declared a budget emergency and agreed to join the National Federal University March scheduled for April 23.

“Under the current conditions, the possibility of maintaining all activities aimed at guaranteeing the quality of education, the continuity of research, extension, and assistance functions is seriously affected,” said UBA.

The call for the march was promoted by the Frente Sindical de Universidades Nacionales (National Universities Union Front), the Federación Universitaria Argentina (Argentine University Federation, FUA) and the Consejo Interuniversitario Nacional (National Interuniversity Council, CIN). Gradually other social sectors (union organizations and collectives) supported the call.

The actions leading up to the march included vigils, open classes, and cultural events. The university demonstrations were replicated in other provinces of the country on the same day, April 23. The entire university system is at risk. The response could not be any less.

Attempts to Silence Dissent

In reaction to the call for the march, the ruling party claimed that there were political interestsother than those of the studentsdriving the call for the march.

In addition, tension persisted regarding the security of the mobilization. There were fears of repression, as occurred during the demonstrations against the so-called Omnibus Law, which sought to deregulate the country’s economy in January.

It is worth recalling that after taking office in December 2023, the libertarian Milei began to promote different measures that resulted in thousands of layoffs of personnel from different public institutions, the reduction of salaries and pensions, among other cuts that have also affected thousands of people who today are also denouncing a food crisis.

At its start, Milei’s government introduced an anti-picketing law to inhibit road closures and blockades, in anticipation of protests in response to the new measures. The administration has deployed the Federal Police, the Gendarmería (national frontier guard force), and the Prefectura (navy) in response to different protests, which have all been peaceful.

However, the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, CABA, is in charge of security in the capital city, and it authorized the march. The operation of the National Security Minister Patricia Bullrich was therefore only deployed around federal government buildings, such as the Casa Rosada. There, they set up metal fences and police officers maintained their presence.

Far From Being “Settled”

The night before the mobilization for public university education, Milei broadcast a recorded message on national television. He assured that his economic measures, the gradual dismantling of the State, were having positive results. He said that thanks to the budget cuts and other actions of his government, they had achieved financial surplus. He spoke of a “hazaña mundial” (worldwide feat) and lashed out at previous governments.

He also stated that a deposit was made to update the operating budget for the universities and, as such, the university issue was “settled.”

His closest staff and those in the Casa Rosada also maintained this position of having “settled” the university issue. Despite the massive demonstration, they opted to say that nothing was going to change and that the interests of his government’s opponents were at stake.

The fight for public university education in Argentina is not new. In different episodes and under different political leaders, students protested to defend their right to education. A right that has never been so threatened in Argentina’s democratic era, which began in 1983 after the dictatorship.

“No University, No Future”

Blocks of young students, drummers, retirees, union workers, families and diverse groups of people packed the areas near the Palace of the National Congress and the Plaza de Mayo, the starting and closing point of the mobilization. They posted stickers, posters, and stencils. They sang and shouted, “Defend education,” “Education belongs to el pueblo, we will defend it,” “Without science, there is no Conan” (Milei’s five dogs are all clones of his dog Conan who died in 2017), “No university, no future,” “Let’s take the streets so we don’t lose the classrooms.

The messages multiplied. So did the shouts. Among the crowds, different scenes took place. A parent told their child that they were observing the struggle for them to have more opportunities in the future. The child, excited, pointed a finger at the demonstrators passing by.

On Avenue 9 de Julio, a group of friends jumped up and down, setting off blue and red flares and beating drums.

A group of veterans met on Callao Street. As they looked at each other they smiled and took some books out of their bags. “Look, I thought it was more than wise to bring the Constitution.” “I brought this one, one of the books I read when I started university.”

One person appeared on their balcony and started clanging pots to encourage the marchers. In response, the young people began to clap their hands, generating a dialogue of sounds.

“Che, there are a lot of us, we can’t go any further. I’m running out of breath, but it’s good for them to see that we are here,” said an older person as they walked towards the Cabildo public building.

The streets of one of the most emblematic areas of Buenos Aires became the scene of yet another symbolic moment in the struggle of el pueblo argentino (the Argentine people).

“Education Sets Us Free”

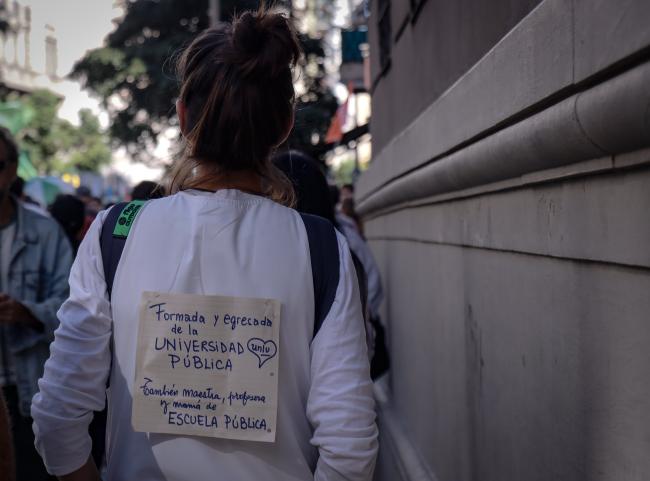

If there is something that unites different social sectors, it is the defense of public education. Many posters pointed out that social mobility in the country has been possible thanks to this right. “Thanks to UBA, today I have a good quality job.” “I was the first one in my family to go to university, I don’t want to be the last one.”

Many social leaders rallied in support of the students. At the closing rally in the Plaza de Mayo, there were union leaders, academics, mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, among others. They outlined what had happened during the first four months of Milei’s government, talked about the setbacks, and the problems. But they called to keep up the struggle, to join the cause.

“I also studied at a public university,” said several others, and shouts of support rang out.

“La educación nos salva y nos hace libres (Education saves us and sets us free). We call on Argentine society to defend it,” said Piera Fernández De Piccoli, president of the Argentine University Federation, from the podium.

In his triumphalist broadcast the night before, Milei said, “The era of the present State is over.” Of course, it’s not why he said it, but the crowd that came out to defend education shows that Argentina is indeed entering another era that will resound in the streets: “Viva la universidad, carajo.”

Lizbeth Hernández is a Mexican freelance journalist and photographer. She covers social movements, human rights, feminism, LGBTI+ issues, migration, women, and territorial defense in Mexico and other Latin American countries. She has collaborated with The Washington Post en Español, El País, Aj+ en Español, NACLA Report, Alharaca, Presentes, Wambra, Animal Político, Contracorriente, Volcánicas, among others.