The images showed volunteers organizing bloodstained clothes, shoes, backpacks, and final notes to loved ones into neat piles alongside charred human bone fragments. Those not wearing hazmat suits wore t-shirts adorned with the faces of their disappeared loved ones. They worked with picks and shovels to unearth hundreds of bloodied personal items.

The grisly discovery was made by the Guerreros Buscadores, or “Warrior Searchers,” a mostly female civilian search collective that has assumed the task of locating lost relatives after years of neglect by state authorities. They had received an anonymous tip that a ranch in Teuchitlán, just outside of Guadalajara in the Jalisco state, was run by the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) and may contain human remains.

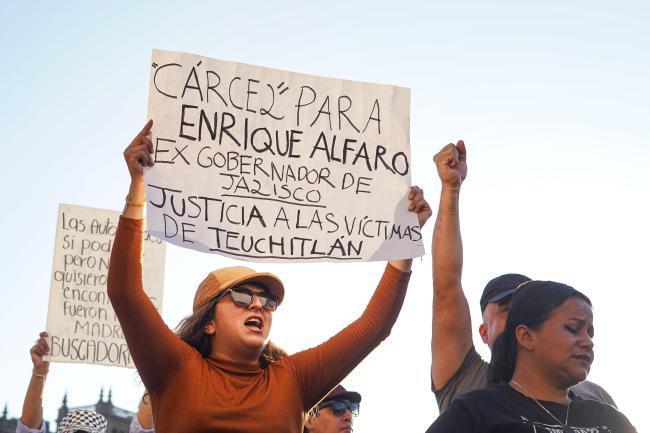

The volunteers shocked Mexico when they released photos on March 5 of the mass grave and alleged crematorium discovered at the ranch. Since the revelation, candlelight vigils have spread across the country, as have protests and calls for state action. The buscadoras have launched a public campaign calling for international support for their demand for answers.

While the images inspired outrage across the country, they have also put some of the women who have spent years searching for disappeared loved ones in the crosshairs of criminal groups and state authorities alike.

The Stigmatization of Searching Mothers

Days after the discoveries at the Izaguirre ranch went viral, several hooded and heavily armed men claiming to be from the CJNG released a video in which they denied the Jalisco Cartel had anything to do with the site. They also accused the civilian investigators of lying.

In the video, a man claiming to be a spokesman unleashed a series of not-so-veiled threats against the women of the search team. Holding an assault rifle and wrapped in ammo, the man said the women have no right to “distort reality” with “false accusations.” He even criticized the “searching mothers” for entering the property at all.

The cartel was not alone in questioning the motives of the women. Some supporters of the Morena ruling party accused the women of sensationalism in an attempt to attack the overwhelmingly popular government of Claudia Sheinbaum. Others blamed the victims of forced disappearance themselves—claiming they brought the violence upon themselves by associating with criminal elements.

“There is often a stigmatization of civilian investigators,” said Laura Contreras, a buscadora from a collective dedicated to the disappeared and victims of femicide in Michoacán known by its Spanish initials as DECOFEM. She explained that their complaints are often ignored by local officials who do not want to be bothered and are sometimes coopted by criminal elements. Her sister, Tania, was disappeared by the Cartel Caballeros Templarios in 2013. “Part of our job is to pressure them to do theirs,” she said.

The recent threats against the buscadoras brought to memory the tensions between the activists and the previous government. In May of 2024, then-president Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) accused civilian search groups and journalists of manipulating government statistics and misleading the public out of “a delirium of necrophilia” after search collectives drew attention to the discovery of a mass grave near Mexico City.

It was far from the only time AMLO attacked the buscadoras publicly.

“Machismo, I think, is also a factor” in ignoring or criticizing civilian women investigators, Contreras said, referring to a dismissive and often misogynistic view of women in some elements of Latin American society. “They don’t want to take us seriously.” Nine buscadoras were killed and one disappeared between 2021 and 2024, according to the Foundation for Peace, a human rights watchdog organization in Mexico.

State Complicity in Mexico’s Disappearance Crisis

Six months before the recent discovery, the Jalisco state prosecutor’s office and the National Guard had inspected the same location. They said in official statements that they had arrested 10 people, rescued two who had been involuntarily “deprived of liberty,” and recovered one body, but found no other human remains.

In a March 11 statement by the Federal Attorney General’s office, the AG said it was “simply not credible” that local authorities could not have known about the site, and faulted the lack of a basic forensic report. The office went on to propose taking over the investigation of the Izaguirre ranch after local authorities said in recent public statements that they had “searched certain parts of the ranch” but could not complete their task because the “ranch is huge.”

Federal authorities have since arrested two Jalisco state police officers in connection with kidnappings believed to be associated with the Izaguirre ranch.

The recent probes and protests by women investigators in Mexico have re-opened an old debate about a lack of political will on the part of authorities to investigate reports of violent crime in the country, which has a nearly 95 percent impunity rate for homicides.

Following the discovery of 24 bodies in another clandestine grave in Zapopan, Jalisco in December 2024, a study by the Committee for the Analysis of Missing Persons from the University of Guadalajara pointed out the “systemic and active involvement” of local police in forced disappearances. According to Jalisco’s Prosecutor’s Office for Disappeared Persons, 306 public servants were prosecuted in forced disappearance cases between 2018 and 2024.

According to official government statistics, 111,916 people have been “forcibly disappeared” in Mexico since statistics began being collected in 1962. That number, however—which does not include those whose remains have been located—has long been a point of dispute among those whose loved ones have gone missing and political leaders alike. NGOs in Mexico have given estimations between 125 to 150 thousand.

The United Nations and Amnesty International have both criticized a lack of transparency in the methodology used to record disappearances, particularly after former president AMLO controversially claimed there were only 12,377 “confirmed reports” of disappearances in December 2023.

“No Body, No Crime”

According to the most recent detailed report from 2024 by the governmental body that keeps statistics on the search process, the National Search Commission discovered 5,600 “clandestine gravesites” that contained more than 52,000 bodies between 2007 and 2023.

“You have to understand that if there is no body, authorities don’t have to deal with an official crime,” said Contreras. “A lot of crimes start as something else, like a rape, or even a barfight that goes too far, and then the perpetrators disappear the victim to hide it.”

To seasoned investigators like Ana Enamorado, who has spent more than 15 years as a buscadora in México, threats from organized criminal groups and state pressure to avoid drawing public attention to those forcibly disappeared are far from new dynamics. Her only protection is a “panic button” given to her by local police. “Sometimes we are surveilled or intimidated,” she said. “And yes, although we feel fear,” that hasn’t stopped her, as women like her are motivated by “our need for justice.”

Enamorado’s son, Oscar Antonio Lopez Enamorado, went missing in 2009 after being lured to Jalisco from Honduras by false promises of work. Shortly after he disappeared, she followed him to Mexico to begin what would eventually become more than a decade-long search to find answers—or, at the very least, his remains. “We fight so that no other mother, sister, or daughter has to endure this,” she said.

Fifteen years later, she has yet to find any trace of Oscar. But as she continues her search, she aids other women in the country who have also lost loved ones as part of the Regional Network of Families of Migrants in South and Central America.

“What’s happening in Mexico currently is incredibly serious,” she said. “It’s a war. I don’t think there is another way to describe it. Violence has become so normalized that it rarely even shocks people anymore.”

She described a long history of apathy on the part of security forces regarding those who have gone missing. She is often told by officials “not to get involved” in criminal investigations. “They tell me it’s dangerous,” she said in a restaurant in Mexico City, where she shared her life story. “They tell me that I could end up interfering with official processes. They tell me to wait, but they do nothing.”

At one point, she was told by authorities that they had found the body of her son Oscar. At first, she believed them, and went to retrieve the remains. But upon further investigation, she learned that police had never performed a forensic analysis or DNA tests on the body. “So, I paid to have it done myself,” she said. “It was not the body of my Oscar.”

Enamorado isn’t alone. Studies conducted by the government have identified thousands of cases between 2006 and 2022 in which a breach in the custodial chain of bodies held by authorities, environmental conditions, or outright incompetence on the part of security forces have made identification of human remains more difficult or impossible.

Others have had the names of their loved ones removed from the national registry, and their cases closed without notice. Some family members have even been accused by government investigators of lying to hide the whereabouts of their missing loved ones.

The State’s Response Falls Short

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has taken a more measured tone with civilian investigators than her predecessor. In the wake of the fallout over the mass grave’s discovery, Sheinbaum called for better protection for the women searchers in public comments, and released a statement calling for six “immediate” actions to be taken against crime and to find those forcibly disappeared. These included strengthening the National Search Commision and establishing new protocols for alerts on missing persons.

Still, activists say the state’s proposed response to the crisis is lacking. “These protocols already exist,” said Enamorado. Two collectives of buscadoras published an open letter to Sheinbaum stating that her announcement “reflects a deep lack of knowledge about the institutional mechanisms and procedures that already exist in the country.” Search groups have called for real material reform of state investigations, particularly at the local level, and repeated long-standing calls for open dialogue with Sheinbaum herself.

The frustration of the buscadoras runs well beyond a disagreement over policy. They claim that their years of efforts looking for thousands of missing people should never have been necessary at all. “The responsibility rests on the state,” they wrote. Instead, say the women, the state has “often been our biggest obstacle.”

Daniela Díaz is a journalist in Mexico focused on implementation of the peace and women’s issues. She has been published at VICE World News, World Politics Review, and a host of Colombian media companies.

Joshua Collins is a freelance reporter in Colombia focused on civil rights, migration, and the impact of crime upon human rights.