On February 15, Petrópolis, a city of approximately 307,000 residents in the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro, received more rain in three hours than the historic monthly average. Mudslides killed 229 people and 20 remain missing. Deaths were concentrated in the low-income community of Morro da Oficina, buried by a mudslide following the historic rains. Classified as “substandard” by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), Morro da Oficina was built precariously on a steep hillside, the result of unequal access to land and the high cost of housing relative to income per-capita. A 2017 study by the municipal government found 15,240 homes in the district at immediate risk.

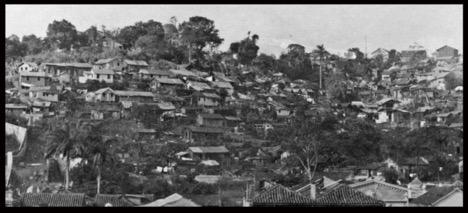

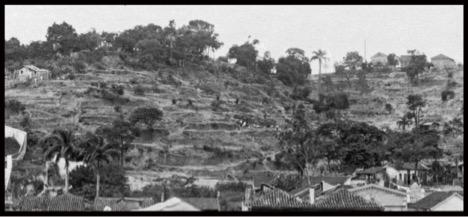

Landlessness and precarious housing are historic problems in Brazil. The privatization of land emerged in direct response to the 1850 closure of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, compelling landowners and the imperial government to design other sources of credit and legal means of labor control. Following the abolition of slavery in 1888, unequal access to land underwrote the conscription of agricultural labor through sharecropping. In urban areas, city officials used control over housing to discipline the free population, waging a sustained campaign of neighborhood demolitions in the name of public health and urban renewal. Such “urbanization” campaigns sought to bring areas of free Black labor, and independent residence under the jurisdiction of city officials. Many of the first images of these communities document only their violent disappearance. The 1916 photographs taken of the Morro de Santo Antônio from the roof of the Teatro da República, for example, are titled simply “ before the action of Public Health” and “ after the action of Public Health.” In the second photo, empty foundations terraced into the hillside are the only remnants of the now-vanished community of clapboard homes.

Today, access to land and housing in Brazil remains starkly determined by class and by race. In the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro, 31 percent of people of color live in substandard housing compared to 14 percent of whites. During the 20th century’s military dictatorship (1964-1985), land concentration enabled the forced transfer of populations from rural to urban areas as a means of labor conscription and industrial development. With the return to democracy in 1985, minimal rights to land and safe housing were protected by law. The 1988 constitutional congress responded to longstanding social movements for land access and housing rights by recognizing the social function of property and the rights of landless persons to up to 250 square meters of land constituting an exclusive residence maintained over five years. These legal protections were expanded in 2001 under Federal Law (L10257) codifying the use of urban property for the public good, thereby paving the way for low-income communities to receive federal funding to improve homes and infrastructure and make underutilized land available for housing.

Since 2016, however, such federal programs have been dramatically scaled back. In 2020, the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro replaced the federal program Minha Casa Minha Vida (My House, My Life), which supported low-income housing, with a new program directing funding towards private construction firms for the development of middle-income units. At the same time, Bolsonaro’s Partido Liberal (Liberal Party) has diverted federal funding from environmental agencies, including the National Agency for the Monitoring and Alert of Natural Disasters (Cemaden), which was created by President Dilma Rousseff after the mudslides in 2011 that killed more than 900 in the region of Petrópolis. Amidst February’s torrential rains, Rio de Janeiro’s governor, also a member of Bolsonaro’s Liberal Party, ignored the evacuation warning issued by the Cemaden. The newspaper Folha de São Paulo reported that the state agency responsible for the evacuation received only 47 percent of its allocated funding for 2021.

This systematic defunding of public services pertains to a larger pattern of governance by Bolsonaro and his Liberal Party. A Senate investigation into executive mismanagement of the coronavirus pandemic last year found them responsible for misinformation and the irregular use of public funds which resulted in deaths and crimes against humanity. The government’s failed response to the pandemic has proven two times more lethal for communities classified as substandard, contributing to the existing forms of environmental violence such communities already suffer.

The 2012 legislation (L12608) that created the Cemaden also made federal, state, and local governments directly responsible for “discouraging the settlement of environmentally vulnerable areas and promoting the relocation of populations residing in such areas.” But in an interview for Revista Piauí, Claudia Renata Ramos of the Movimento do Aluguel Social e Moradia de Petrópolis (Petrópolis Social Rent and Housing Movement) described how political attention in the wake of the disaster has once again failed to center the underlying question of housing inequality. In a clip aired last week on the podcast Foro de Teresina, Ramos observed that “despite all the commitments made by our politicians, despite all the politicians coming here to Petrópoliseven the president will be arrivingask if they have gone to the bairros or looked for the social movements working with those communities.”

Petrópolis represents a clear omission of rights to safe housing protected under L12608 and articles 182 and 183 of Brazil’s Constitution. As socially induced environmental change makes marginalized communities like Morro da Oficina even more vulnerable to climatic disasters, they are also protected by the Constitution’s article 225, which guarantees the rights of citizens to an “ecologically equilibrated environment.” In actuality, this remains a gray area of Brazil’s environmental law. More often than not, environmental laws have been used to justify the eviction of landless persons and marginalized communities without democratic processes of consultation, compensation, adaptation and/or relocation. No clear legal precedent exists to adjudicate responsibility for the larger structural circumstances that have put certain communities at environmental risk, nor create accountability for the loss of life caused by an environment thrown out of “equilibrium” by the privatization of land, the commodification of housing, and the commercial extraction of fossil fuels. But this is in fact the immediate political question posed by the landslides at Petrópolis: what justice does Brazil’s Constitution provide for the victims of such an unnatural disaster?

Chris N. Lesser is a doctoral candidate in Geography and Earth and Ocean Sciences at The University of California, Berkeley and the Universidade Federal Fluminense, in Rio de Janeiro.