The Colombian government and the ELN, the largest remaining guerrilla group in Colombia, completed their first phase of direct negotiations on Monday. As conflict continues to rise in rural areas, the stakes could not be higher for residents of ELN strongholds, where forced displacements have become commonplace, and armed groupsrather than the governmentimpose the law. This is the seventh round of attempted peace talks with the Marxist rebel group since it was formed in 1964. The latest round of talks began on November 21 in Caracas, Venezuela, moderated by representatives from Norway, Chile, Mexico, Venezuela, and Cuba, as well as representatives from the United Nations and the Catholic Church.

A ceasefire has yet to be reached, but in a joint statement by the ELN and Colombian government the parties announced agreement on a series of points detailing how talks will continue, as well as beginning “emergency humanitarian measures” in zones most affected by ongoing conflict.

“Here in Colombia we all have to change,” said Pablo Beltrán, chief negotiator for the ELN, in a press conference Friday, announcing the end of the first round of talks. “But we must all remain committed [to the peace process]. Colombians can no longer view one another as enemies,” he said, insisting that they must all strive towards “building a nation of peace and equity.”

President Gustavo Petro has described a peace accord with the ELN as a key first step in what he calls “Total Peace” for Colombiaan ambitious plan that involves direct negotiations with all willing criminal armed groups in the country.

The ELN is the first large armed organization to formally begin talks with the Colombian government since the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) demobilized in 2016. Some “blocs” of the Gaitanista Self Defense Forces (AGC), often referred to as the “Clan del Golfo” by the government, have expressed willingness to negotiate as well. The AGC is the largest criminal group in the country and grew out of the paramilitary forces that fought on the side of the government during the civil war with the FARC.

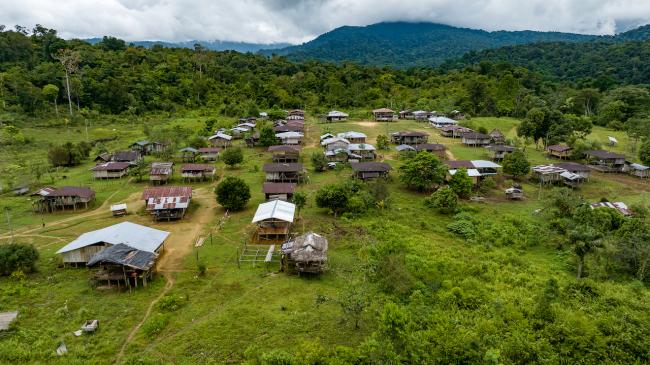

Colombia is still reeling from the after effects of 52 years of civil war with the FARC guerilla group, which was marked by highly aggressive military strategies and social crackdowns on the part of the government and their paramilitary allies, with U.S. support. Petro promised on the campaign trail to move away from the failed military strategies of previous administrations by opening talks with the myriad armed groups who still operate in the country, in addition to building infrastructure in conflict zones. To do so, he will need to overcome not only complicated security, logistical, and political challenges, he will also need the support of the communities who live in conflict areas. These territories have been neglected by the government for decades, and regaining that trust won’t be easy.

In regions like Catatumbo in eastern Colombia near the Venezuelan border, which is one of the biggest coca producing regions in the world, skepticism runs deep.

“The community has very little faith that the government will live up to its word. We’ve heard these promises before,” said Andrés Silva Rojas, a farmer who advocates for sustainable farming practices among coca growers in the region. The Colombian government is totally absent in Catatumbo. Instead most of the area is completely controlled by ELN forces.

Rojas explains that many in the community strongly supported the country’s historic peace deal with the FARC in 2016. But the government’s promises to build infrastructure and create economic opportunities outside of illicit markets never materialized. Instead, renewed violence between armed groups in the region and aggressive military operations that have at times targeted residents themselves, have convinced many that the government is unableor unwillingto implement real reform.

“In 2016-2017, a lot of these farmers took real risks signing up for crop substitution programs, promising to move away from coca if the government provided other options,” said Rojas. “Six years later the guerrillas are still in charge here, no payments for those crops ever arrived, and we still live without serviceable roads, medical care, state education, and in many cases even without potable water,” said Rojas. “The only time we see the government is when they come to burn our [coca] fields down.”

Violence in rural areas has grown considerably since the 2016 peace deal with the FARC was signed. Petro has promised to fully implement the historic peace accord of 2016, especially government investment in infrastructure and economic opportunities in formerly FARC controlled areas, which have been the focal point of increased violence. Former president Iván Duque, who was elected on a campaign promising to dismantle parts of the historic accord, preferred aggressive military solutions to social strategies. For four years, his administration stonewalled or reneged on promises of investment and state-building to fill the vacuum left behind when FARC fighters disarmed en masse.

That vacuum was quickly filled by other criminal groups instead. The ELN, and their bitter enemies the AGC, have both rapidly expanded into formerly FARC-controlled areas since Colombia endedat least on paperits more than half-century of civil war.

Between January and August of this year, nearly 55,000 people were directly displaced by violence in Colombia, the highest number registered since 2015, prior to the FARC’s demobilization. The Norwegian Refugee Council estimates that over 100,000 people were subjected to forced confinement by armed groups between January and November because of threats, active fighting, or transportation restrictions that the groups have imposed.

And fighting between armed groups over territory for extorting residents, smuggling corridors, illegal mining, and coca cultivation regions has skyrocketed. In 2021 coca production in Colombia reached historic highs, according to an October report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, an increase of 43 percent over the previous year. The Red Cross Colombia identifies five separate conflicts raging currently in the country, all of which involve the ELN at least to some degree.

“The guerillas were shooting from near one group of houses, and the paramilitaries near another,” said Margarita Mondragon, a social activist in Santa Rosa, in the northwest department of Bolivar. “The gunfight occurred right in the middle of civilian housing, catching residents in the crossfire,” she continued, referring to a confrontation between the ELN and the AGC in October.

Mondragon describes violence and forced displacements as simply part of daily life. She firmly believes military strategies have only made the situation worse and that “negotiations are the only way to resolve this endemic problem.” But she also feels that representation of affected communities at the bargaining table, something both the ELN and the government have said is crucial to the success of the talks, is sorely lacking.

“It isn’t clear if the ELN representative negotiating in Caracas even speaks for the front’ of ELN in my community,” she said. Talks have been complicated by the fact that the ELN does not have a clearly vertical command structure like the FARC did. Instead, it is made up of semi-autonomous “fronts,” a factor that complicates negotiations.

When asked if residents in his community have been consulted or informed about ongoing talks that will affect the future of Catatumbo, Rojas replied, “absolutely not.”

In last Friday’s press conference, Otty Patiño, the government’s representative in the negotiations, admitted that this is an area of the process that needs to be improved, stating, “there has been representation of Colombian society, but we must work on incorporating more sectors, and there will be consultations with more community groups.”

For residents who live in affected areas, the situation couldn’t be more urgent. Conflict in Arauca, another department on the Venezuelan border, between the ELN and an ex-FARC dissident group that rejected the 2016 peace deal, flared up in January and has recently worsened. Killings also continue in Cauca, Chocó, Nariño and northern Antioquia, all areas with a heavy ELN presence.

An all-time record of 199 activists and social leaders have been killed in Colombia so far in 2022.

Although Mondragon fears that some of the ELN fronts will not agree to peace and become “dissident” groups like some FARC regiments did in 2016, she is hopeful about the talks. “Unlike past negotiations, ELN is dealing with a democratically elected leftist president, and following massive popular protests [in 2021],” she said. “This is a very different situation than the last talks in Cuba, and the guerrillas know disarmament has popular support.”

Rojas is more circumspect. “We’re just doing what we have always done as a community. As you know, we lead very individual lives. There is no government here.”

Rojas described by phone how heavy rains washed away the only road to his town, leaving him unable to leave his farm for weeks. He takes a “believe it when he sees it” attitude towards the talks.

“Maybe they can start by building us those roads they promised six years ago.”

Joshua Collins is a freelance reporter in Colombia focused on civil rights, migration, and the impact of crime upon human rights.