Para leer este artículo en español, haz clic aquí.

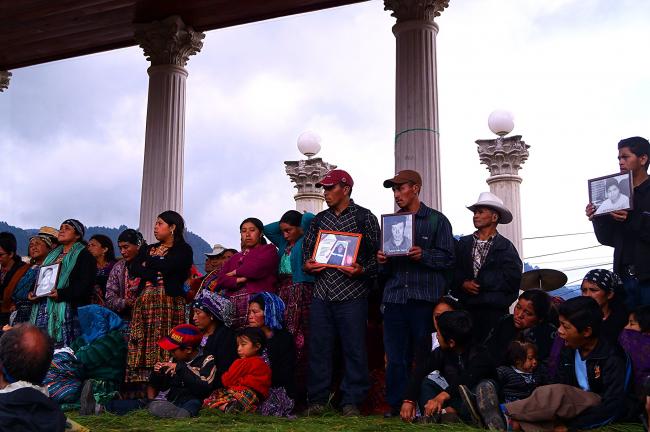

In the last decade, national protests throughout Guatemala have symbolized a growing anger and mistrust towards a historically corrupt and genocidal government that has looked out for the interests of the oligarchs, criollos, gringos, foreign corporations, and landowners. On October 4, 2012, the Indigenous authorities of the 48 Cantones of Totonicapán organized thousands of people to block the Pan-American Highway to call for constitutional reforms and denounce high electricity prices, among other demands. The military and the police, sent in to brutally end the protests, fired on unarmed people at the Cumbre de Alaska, killing six and injuring over 40. It was the first known state-sponsored massacre since the end of the war in 1996.

Nine years after the Alaska massacre, those responsible continue to live in impunity. After repeated stalling, the case crawled forward on September 3 when a judge sent a colonel and eight soldiers involved to trial for extrajudicial executions. The case’s slow progress is a reminder that even though the war ended, the violence continues, and while peace was declared, there remains no justice for victims or accountability for the perpetrators of human rights crimes, who continue to hold considerable power in Guatemala. The end of the war also signaled an increasing invasion of extractivist industries, with the support of the oligarchs, and further displacement of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories.

Despite the threat of violence, the communities of Totonicapán, and other Indigenous and campesino communities, continue to resist. Today, Maya, Xinca, and Garifuna communities and ancestral authorities from throughout Guatemala, and national organizations such as CODECA (Committee for Campesino Development), are at the forefront of protests that seek to challenge the colonial and dominant structures that have existed in Guatemala for the last 500 years.

#ParoPlurinacional

On July 29, thousands of people took to the streets and blocked highways throughout Guatemala to call for the resignation of President Alejandro Giammattei; one of the largest concentrations took place in Totonicapán. Several subsequent protests and blockades led by ancestral authorities and CODECA continued in August.

The recent wave of protests and national strikes continues those that began years ago. In 2015, mass protests over the La Linea corruption scandal led to the resignation of former president Otto Perez Molina, who is currently on trial, along with other former high-level government officials, for racketeering, fraud, and illicit enrichment. The United Nations anti-corruption unit, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), spearheaded the investigations. Despite CICIG’s gains in combatting impunity, structural change was not achieved, and there was swift backlash from the Guatemalan State. After a series of moves to weaken CICIG, President Jimmy Moralesflanked by 68 uniformed military membersannounced in August 2018 that he would not renew the body’s mandate. Then, during the 2019 elections, former Attorney General Thelma Aldana, who worked closely with CICIG, was barred from running for president, charged with trumped up crimes, and forced into exile. She gained political asylum in the United States in 2020.

In November 2020, the Guatemalan Congress voted to decrease funding for human rights and health programs, such as fighting malnutrition, and increase funds for lawmakers’ meals and expenses. The move, which came amid the Covid-19 pandemic and in the wake of two destructive hurricanes, triggered new protests against the government. During the demonstrations, fire was set to the Congress building in Guatemala City as thousands took to the streets. Known on social media as #NoNosPela, the protests expressed outrage over the mishandling of the pandemic and hurricane relief effortsproblems that continue to impact people today. The demonstrations were seen as a continuation of the 2015 movement.

In April 2021, Congress prevented Gloria Porras, a judge known for fighting corruption, from taking her position within the Constitutional Court. Human rights groups expressed concerns that Porras’s exclusion would further debilitate an already weak justice system and that many legal cases, including those regarding struggles against megaprojects and the prosecution of war criminals, would be seriously hampered. Then, on July 23, Attorney General Maria Consuelo Porras fired the head of Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI), Juan Sandoval. FECI worked alongside CICIG in investigating government officials and corruption, and it has continued to do this work since CICIG’s expulsion. Sandoval’s illegal and arbitrary firing took place soon after FECI began investigations into President Giammattei, including for allegations that he accepted bribes from a foreign-backed mining company. Sandoval was forced into exile, adding to a long list of those forced to flee Guatemala for their work in denouncing corruption and impunity. In exile, Sandoval claimed that “the Guatemalan justice system has been overtaken by the mafias in power,” and that Porras was a “friend” of the president who obstructed FECI’s investigations into Giammattei and other government officials. On September 3, Guatemalan prosecutors issued a warrant for Sandoval’s arrest, and the Constitutional Court declared that those who are found guilty of corruption can avoid receiving a prison sentence.

Sandoval’s dismissal triggered national protests and a national strike that has again placed Guatemala at a political and social crossroads. But the protestssome of the largest since the 2015 anti-corruption uprisingare not just about Sandoval’s firing. Rather, they represent a larger historical trajectory that seeks to push back against the dominant powers in Guatemala that have caused harm while treating the country like their private finca (plantation). These dominant powers include capitalist business interests, represented by CACIF (Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and Financial Associations), government officials, the military, and foreign corporations, among others. These dominant and repressive powers have come to be known as the “Pact of the Corrupt” (Pacto de Corruptos). CACIF in particular wields considerable power. Oligarchs own Guatemala’s largest businesses, such as fast-food chain Pollo Campero (owned by the Gutierrez family) and beer label Gallo (owned by the Castillo family). CACIF has labelled the blockades as “illegal” and criminalizes protesters. As a result, there are calls in Guatemala to envision a “Future without CACIF” (#UnFuturoSinCACIF).

The Indigenous communities, ancestral authorities, and campesinos that have historically resisted state violence again have been at the forefront of these protests, as they have been the primary forces organizing strikes and blockades throughout the country. Their demands range from calls for the resignation of Giammattei and Porras to structural changes that include a plurinational constituent assembly. Thelma Cabrera, a member of CODECA, which has led calls for a plurinational state, explains that resignations alone are not enough. “As a people, we have been excluded, discriminated against, exploited, impoverished,” she says. “We propose a process of a Constituent Assembly, that the peoples be represented through a Plurinational State, with autonomy and representation of all the peoples that inhabit Guatemala.” Through the protests, she says, “the people rise up in the face of a system that oppresses us and that excludes us, exploits us, murders and imprisons us.”

While global media coverage of protests in Guatemala often centers Guatemala City, Indigenous and rural communities have often been in active resistance. In response to the protests, Giammattei has militarized the country by declaring multiple states of prevention and states of calamities, which restrict public gatherings and civil liberties, often using the pandemic as the justification and excuse.

Covid-19, Natural Disasters, and Displacement

The gross mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic and the response to the 2020 Hurricanes Eta and Iota demonstrates the ineptitude, incompetence, inability, and unwillingness of the Guatemalan State to protect and promote the well-being of the people. For instance, aid for victims of the hurricanes has been politicized, with one report of 1,000 bags of rice being sent to the president’s Vamos political party headquarters in Cotzal. In August 2020, with the need for medical doctors more urgent than ever amid the ongoing Covid-19 emergency, one member of Congress advocated for the expulsion of Cuban doctors from Guatemala. Also during the pandemic, starvation led many to beg on the streets and wave white flags to ask for help. Communities confronting the long-term effects of the hurricanes, which damaged roads and destroyed crops, are at greater risk of hunger.

Meanwhile, the government’s Covid-19 response has raised suspicions of corruption. The Giammattei administration purchased 16 million vaccines for $80 million, but the doses never appeared. Instead, Guatemala has relied on donated vaccines, but they have not been enough as only 4.5 percent of the population (mostly concentrated in urban centers) has been fully vaccinated. Of Guatemala’s 340 municipalities, 289 (85 percent) are in alerta roja (red alert), the highest risk category within the country’s four-tier Covid-19 alert system; 32 (9.4 percent) in the second highest risk category; 19 (5.5 percent) in the third highest risk; and none in the safest category (green). With over 11,000 people dead from Covid-19 and one of the lowest vaccination rates in the western hemisphere, people have asked: Where are the vaccines? (#DondeEstaLasVacunas) and where is the money? (#DondeEstaElDinero).

Even the Guatemalan consulate in Los Angeles has been implicated in corruption; Consul General Tekandi Paniagua was removed in June 2021 for mismanagement of aid for hurricane victims and profiting from selling Covid-19 tests. A Los Angeles Times report found that “more than $100,000 in masks, food, medical supplies and personal hygiene items collected in Los Angeles, in November 2020, to help those affected by hurricanes Iota and Eta did not leave for the affected communities in Guatemala; instead, they had begun to be distributed by Consul Paniagua to local entities.” The consulate in Los Angeles was also implicated in a scheme that saw Guatemalan immigrants charged up to $175 to take a Covid-19 test (which are free at the consulate) and not provided with a receipt.

Structural inequalities and violence in Guatemala have been the leading factors forcing thousands to migrate and live in exile abroad since the 1970s. These conditions continue today. At the same time, border militarization, and the dehumanization and criminalization of migrants also negatively impact Indigenous peoples and Guatemalans who face human rights violations by U.S. and Mexican government officials. For instance, U.S. state-sanctioned kidnapping of children continues under the Biden administration. Hundreds of unaccompanied minors and children have been placed in harsh living conditions without their parents as family separations are used as a cruel form of deterrence. This includes children being incarcerated in military bases such as Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, where a tent city was created in March 2021 to house up to 4,000 children and teenagers. In July, whistleblowers denounced “gross mismanagement” and “organization chaos,” such as the failure to provide minors with clothing, as well as filthy conditions, inadequate Covid-19 measures, dismal mental services, and a lack of oversight and accountability at the site. The Biden administration’s refusal to eliminate Title 42a provision that uses the risk of contagion to justify the rapid “expulsion” of migrants from the United States, placing migrants in a vulnerable position in Mexicodespite knowledge of its ill effects demonstrates their cruel position towards migrants fleeing Guatemala and elsewhere.

Intergenerational Struggle Towards the Future

In 1820, the communities of Totonicapán rebelled against the abuses of the Spanish. They created their own government that lasted nearly a month under the leadership of Atanasio Tzul, who was named governor. Subsequently, the colonial armed forces were sent in to end the movement, the communities were repressed, and Tzul and others were imprisoned. Their legacy is often erased within official historical narratives that center Eurocentric and non-Indigenous histories. The following year, the criollo elite declared independence from the Spanish, and they eventually formed the Guatemala state, which would exclude Indigenous and Black communities.

Two weeks before the firing of Sandoval, the representatives from Totonicapán travelled to the National Palace of Culture in Guatemala City to recover Tzul’s chair, which had been confiscated and housed by the government in a museum. During the ceremony, Martin Toc Sic, the President of the 48 Cantones stated:

Atanasio Tzul’s dream was to have a fair country, with opportunities After 201 [years], the 48 Cantones remain strong, more convinced than ever that this country deserves an opportunity; an opportunity where we all feel free, proud of our authorities…The 48 Cantones will always demand opportunities, and not only for Totonicapán, but for the entire country. The [return of the] chair was an obligation of the state [and] today we take it with the commitment to continue doing our job well, ad honorem, because that is how our parents taught us to work without receiving anything in return and that is how it will always continue.

Tzul’s chair is a symbol of intergenerational struggle and resistance, and hope for a better future.

Guatemala today is at another political juncture in a long trajectory that has seen repressive powers exploit, displace, and persecute Indigenous and oppressed peoples. Historical long-standing demands from social movements and calls for a plurinational constitutional assembly underline how real and effective change must be structural if the state is to respect the dignity and well-being of its people.

Giovanni Batz holds a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin and is currently a President’s Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Native American Studies at the University of California, Davis. His publications can be found here.