Amor prohíbido murmuran por las calles

Forbidden love they murmur in the streets.

–Selena, 1994

No puedo ser feliz

No te puedo olvidar

Siento que te perdí

Y eso me hace pensar

I can’t be happy

I can’t forget you

I feel like I lost you

And that makes me think

– Ignacio Jacinto Villa, 1954

I

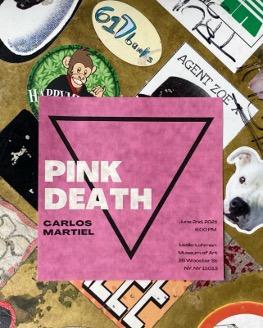

You are unable to attend the performance, Muerte Rosa/Pink Death, at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art in New York on the evening of June 2, 2021, made by one of your closest friends, one of your sisters, Carlos Martiel. Martiel is a visual and performance artist born in 1989 in Havana, Cuba. They escaped the Cuban regime in 2012, migrating, sexiling, and living all over Latin America, working as a cook, messenger, and delivery person. Restrictions on travel and movement because of the Covid-19 pandemic prevent you from being at the performance in person. But your blood is there.

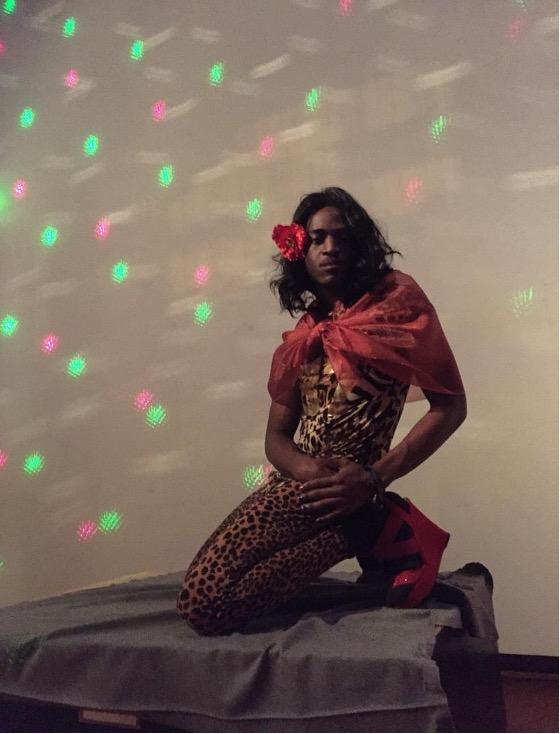

Leslie-Lohman is having its first public event since closing at the beginning of 2020. And there is Martiel, standing nude and in silence for hours, pinned to the wall by one side of an inverted triangle. The triangle is formed by a large string soaked with your HIV-positive blood. The waves of visitors who enter the museum space may choose whether to join the fleeting silhouetted geometry.

“In Nazi Germany, a small piece of pink cloth in the shape of an inverted triangle was used to identify homosexuals, bisexual men and transgender women in concentration camps,” Martiel explains on the back of a pink-hued flyer visitors receive upon entering the gallery. “Decades later, during the HIV/AIDS pandemic of the 1980s in the United States, the pink triangle was reappropriated in a vertical position as a symbol of resistance and solidarity.”

Martiel’s flyer continues:

Pink Death is a performance inspired by the experience of one of my closest art friends, [Georgie] Sánchez, who has been living with HIV since 2018. It refers to the situation of vulnerability suffered by BIPOC communities in the United States and the Caribbean.. This reality is linked to stigmatization, racism, poverty, HIV criminalization, and the lack of access to an adequate health system…

Your collaboration with Martiel requires an exchange of blood, a blood pact, created in part from the undetectable entanglements between HIV/AIDS, art, cuir/kuir/queer/trans activisms, and anti-colonial futures and fissures. A blood pact can take the form of an action, or even a question. For example, what material practices of collective repair have responded to the state and social violences that have radically curtailed cuir/kuir/queer, travesti, and trans lives from the early HIV/AIDS crisis until today?

II

Holding each other tightly, catwalking, pussy-walking, up and down the streets of New York, Martiel and you are singing, gesturing, and imitating divas Ivy Queen, La Lupe, Isabel Pantoja, Cardi B, Lola Flores, Violeta Parra, or Mercedes Sosa until your lungs fail you. Martiel tells you, “Una se compone de fortalezas cósmicas pero también de quebrantos.” One is constituted by cosmic forces but also by ruptures/fissures. Martiel’s mentor, visual artist Tania Bruguera, used to tell you, “Debemos estar en sincronía con el tiempo político.” We must have political timing specificity.” Fucking likewise requires an attunement with political time. Dime con quién chingas y te diré quién eres. Tell me who you fuck with, and I’ll tell you who you are.

Love, lust, and friendship, just like blood pacts, are political acts, as reflected in the political slogans: “No existe sexo sin racialización” (there is no sex without racialization), “la heterosexualidad es un proyecto colonial” (heterosexuality is a colonial project), “lo queer no te quita lo racista (being queer doesn’t make you any less racist). Contemporary Artists, activists and writers from the global majority like iki yos piña narváez, Francisco Godoy Vega, Lizette Nin, Lucia Egaña Rojas, Duen Sacchi, Mag de Santo, Leticia Rojas Miranda, and Colectivo Ayllu have already for years now been actively reminding us of this. How can we politically [a]synchronize our ruptures, our quebrantos, and our colonial wounds?

III

Muerte Rosa begins the same way you begin any shared activity, by way of chismeando (gossiping) or by going to a protest. During one of your conversations on the topic of the material and psychic effects of racialized violence, epidemics, and sexuality, Martiel tells you:

I’ve lived social injustice. I’ve eaten it for breakfast. I’ve gone to sleep with it. It is right under my skin. People don’t realize that racist violence and social injustices are negative vibrations or rhythms that played over and over can have severe pathological consequences on our bodies and psyches. Through visceral political critiques often using my body, I address contemporary issues and social injustices related to censorship and oppression.

In an attempt to neutralize these negative vibrations or rhythms, you decide to make a collective action that speaks to a shared experience of racist violence and social injustice. You create a piece that enacts a shared visceral political critique: a sharing of blood, a sharing of a wound, viral and unseen, an undetectable colonial wound, connecting you across generations of sickness, a genealogy of HIV/AIDS in which non-white bodies continue to experience the weight of pandemics. You choose to make this blood sharing a gesture of friendship. You conjure a language of the heart—the central muscle that pumps blood—in which love is one of its fundamental ingredients.

IV

You are talking with Martiel about a historic gathering you find significant, “The Personal and the Political: Losing Parents to AIDS,” held in 2014 at the New York Public Library and hosted by HIV/AIDS historian, novelist, and activist Sarah Schulman, queer journalist and teacher Mathew Rodriguez, artist Kia Michelle Benbow, known professionally as Kia LaBeija, and author Alysia Abbott.

During the event, Schulman asks everyone in the audience who has lost a loved one or a family member to HIV/AIDS to raise a hand. Along with dozens of people in the crammed 150-seat Celeste Auditorium, you raise your hand. You share with Martiel that this is the first time you publicly identify as belonging to this genealogy. Four years later, at the Callen Lorde Community Health Center, you are told you are living with HIV, just like your late uncle, Edgardo Sánchez.

You witness how certain gains in mainstream LGBTQI+ culture displace, exclude, and dispossess non-white queer, trans, and travesti communities. Recalling the decade-old flash art collectives Queer Crisis and Undetectable, facilitated by ACT UP and Gran Fury activist Avram Finkelstein, you think of the concept of undetectability as a framework for studying overt and subtle representations of HIV/AIDS in cultural production, queer identity, and the persistence of ignored sexually dissident experiences in art and art history.

Turning back time, going against a “chrononormativity,” a term Elizabeth Freeman uses in her book Time Binds (2010), you feel a carnal and emotional connection with the past your uncle has lived. Every day, you wake up to a virus inside of you, trying to kill you. Even after your uncle’s death, that virus becomes a fleshy and muddy creature binding the two of you together, forming a viscous genealogy—a history of both of your bodies, your bloodlines: an hourglass waiting patiently and running on gravity to mark the occasion when your age will unavoidably meet his age at time of death. This viral creature is also an unfulfilled wish. You barely remember him telling you of his desire to move to New York, to leave everything behind. Things would be different in the United States, he said, unlike in Puerto Rico; you remember promises of better health care, better jobs, and an “American dream.” But you remember his side-eye and you laugh out loud, realizing that the only American dream today is a large mall with empty, unopen stores in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

In her book, Freeman criticizes capitalism’s temporal synchronization of bodies for generating heteronormative sociality. Arguing in favor of an “erotohistoriography,” she urges the use of the body as an escape, as a “tool to effect, figure, or perform” encounters with history that are asynchronous, non-heteronormative.

Your uncle’s own timeline transports you to the activism of Puerto Rican Moisés Agosto-Rosario, the cofounder of the Latina/o Caucus, a New York working group of ACT UP, which was most active between 1990 and 1994, the years when your uncle first learned he was HIV positive. Written in 1991, a poem from his book, Poems of Immune Logic, articulates the colonial origins of HIV/AIDS. Titled “Retroira/Retro-ire,” the poem visualizes HIV/AIDS as a different illness, an “Acquired Immunocolonialism Syndrome (AICS)” dating back to 1898, the year the United States invaded, bombed, and occupied Puerto Rico.

Agosto-Rosario’s poem configures the ongoing HIV/AIDS epidemic as part of the colonial matrix of power at play in the death or survival of queer, travesti, and trans people of color. Here, the merging of “retro” (to look backwards) and “ire” (anger) acts as a prism to examine how colonial violence, systems of neglect and oppression, as well as disease are deeply intertwined across a multiplicity of timelines and geographies. There is a specific ire, an anger, that blends with the HIV virus, a retro or past ire, against the virus of colonialism, dating back to 1492.

You feel the retro-ire. The poem’s rhythm connotes an urgency. Words like “baggage” and “cunty plethora of pertinent infections” evoke a sense of historical aggregation—colonialism as an ancestral weight, wounds upon wounds—while the line “cross the pond” suggests a flow of bodies and disease—even your own story of sexile from Puerto Rico. “Tamarind or guava” emplace the poem in colonial landscapes, architectures of consumption and extraction. These delicious fruits are contrasted with the reality of the holocaust of HIV/AIDS: “the people are [still] dying,” a collective loss shaped by colonial histories and systemic inequities. The poem highlights how these deaths, which are rooted in racial capitalism, are rendered invisible or ungrievable within dominant visual and political systems.

V

“Great art can only be created out of love,” wrote writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin in a 1965 text introducing an exhibition of paintings by one of his closest friends, Beauford Delaney. In this political moment, and amid global climate crisis, what are the material conditions of love and intimacy, whether remote or in person? How do we practice intimacy when, as Baldwin similarly described elsewhere, we are dealing all the time with the “most inarticulate people… totally unlettered in the language of the heart”? bell hooks asserted in All About Love that “love is a force as real as gravity” and “an action rather than a feeling.” Today, she explained, still “far too many people in our culture do not know what love is,” nor do they know that “the choice to love is a choice to connect—to find ourselves in the other.”

In the edited collection AIDS and the Distribution of Crises (2020), scholar C. Riley Snorton rethinks HIV/AIDS in relation to “the prison, or living under occupation, or in underdevelopment, or living while Black, while trans, while undocumented, while poor.” In other words, under the intensifying and poisonous tentacles of racial capitalism, death continues to be forced upon marginalized groups. Snorton proposes instead a useful framework for rejecting the terms and conditions of existing HIV/AIDS discourses—a useful rejection that can be mobilized to shade existing cultural and art historical discourses. Snorton writes, “to engage in critical analyses of HIV/AIDS means to refuse the terms on which HIV/AIDS has been given; to refuse its biopolitical and necropolitical machinations; to refuse the representational structures that present some deaths as the requirement for the optimization of life itself; and to insist on different vocabularies for living, which involves asking more and better questions as well as laying claim to the survival of the damned.”

Where can you find this different vocabulary for living, this language or grammar of the heart? Martiel tells you that they see the performance artist as a behique, a pagan saint, or a Taíno doctor. They don’t mean the saints on altars, the scapegoats, or intellectual terrorists. They mean that “art is born out of the need to express the inner conflicts of human beings… to connect with whomever, regardless of your birthplace, your skin color, or your gender.” The “ritualization of the body through art creates empathy,” they tell you.

The act of sharing blood with Martiel shows you different ways of being in the world. Here, you understand that the “chromapolitics” of blood—to borrow a term from feminist theorist Tina Campt—signal life-force or fuerza vital. Sharing the blood may be a way of feeling the gravitational pull of radical love that hooks writes about, an action or utterance of a different vocabulary of being, like Snorton suggests—one of the ways towards languages of the heart.

Georgie Sánchez is a writer and Ph.D. student in modern and contemporary art at Princeton University. Georgie’s writings have been published by the Instituto de Cultura Puertorrriqueña, the Leslie Lohman Museum of Art, Anomaly Journal, the Queens Museum, and The Journal of New Jersey Poets, among others. Georgie’s writings, photographs, and curatorial commitments address Latinx & Diaspora studies, HIV/AIDS, Queer/Cuir perspectives, and sexual dissidence.