This article was originally published by openDemocracy.

It was inconceivable, just five years ago, that ultra-conservative Colombia would decriminalize abortion, or that Catholic, neoliberal Chile would be gearing up to vote on a new constitution that enshrines sexual and reproductive rights, including on-demand abortion.

Yet in February, Colombia’s constitutional court removed abortion (up to 24 weeks) from the criminal code in response to a court case brought by Causa Justathe spearhead of a wide-ranging social and legal campaign of more than 120 groups and thousands of activists.

Colombia is now “at the forefront of the region and the world,” according to doctor and feminist activist Ana Cristina González, a spokesperson for Causa Justa.

The campaign, launched in February 2020, “was the result of political build-up, national and internationally” that changed “the public debate on abortion in Colombia” and became a “collective and articulated movement,” González explained at a meeting in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Abortion was banned completely in Colombia until 2006, when an initial constitutional court rulingprompted by several of today’s Causa Justa activistsdecriminalized terminations on three grounds: if the life or health of the woman was at risk; in cases of severe fetal abnormality; and if the pregnancy was the result of rape.

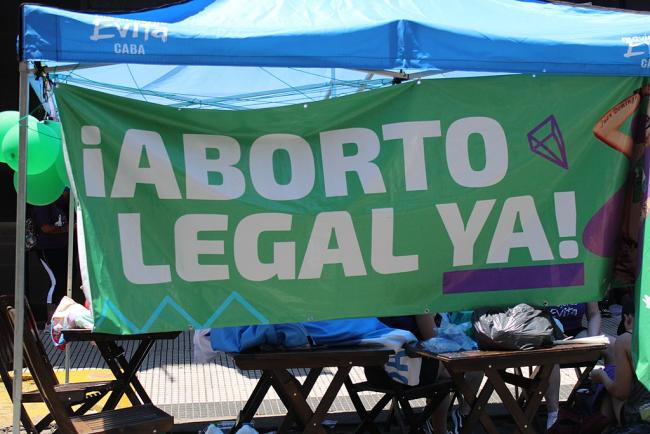

A similar breeze was blowing in Uruguay in 2012, when the country legalized abortion up to 12 weeks. And again in 2020, when Argentina’s parliament passed a law to allow abortion up to 14 weeks, after a decades-long struggle. The green tide, named after the green scarves worn by campaigners for legal, safe and free abortion, inspired and energized the whole region.

Advances in Chile and Mexico

Latin America continues to push the limits of what is possible. Barely a month after the Colombian ruling, Chile’s constitutional conventionwhich is drafting a new constitution for the countrypassed (by a large majority) an article enshrining sexual and reproductive rights as fundamental and guaranteed by the state. These rights include abortion on demand.

The article establishes that “all people are holders of sexual and reproductive rights [including] the right to decide freely, autonomously and in an informed way about their bodies, the exercise of sexuality, reproduction, pleasure, and contraception.”

In addition, the state will guarantee the exercise of these rights “without discrimination, with a focus on gender, inclusion and cultural relevance,” and “assuring all women and persons with the capacity to gestate, the conditions for pregnancy, for voluntary termination of pregnancy, and for protected and voluntary childbirth and maternity.”

Abortion was banned in Chile in all instances during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship and only permitted in 2017 in cases of rape, fetal inviability, and risk to the woman’s life. The public will vote on the new constitution in September; if approved, it will become the first country in the world to give constitutional status to the right to abortion.

Last year, Mexico’s supreme court ruled the criminalization of abortion unconstitutional, and invalidated a federal law that allowed health personnel to refuse to perform terminations on the grounds of “conscientious objection.”

This ruling means no woman can be imprisoned for ending her pregnancy, sets jurisprudence, and puts pressure on states to legalize abortion.

In fact, seven Mexican states have already legalized voluntary abortion up to 12 weeks, five of them in the last 18 months: Mexico City (2007), Oaxaca (2019), Veracruz, Hidalgo, Baja California, Colima (2021), and Sinaloa (2022).

Today, 37 percent of Latin America and the Caribbean’s population of 652 million live in countries where women have won rights to legal abortion or are no longer imprisoned for terminating a pregnancy (including Cuba, Guyana, and Puerto Rico). Five years ago, it was less than 3 percent.

None of this would have been possible without feminist activism, networks and demonstrations, and public conversations about the autonomy of women.

In addition, thanks to feminist innovation and advances in medicine, the mortality rate from illegal abortions has been falling consistently. Between 2005 and 2012, the number of treatments for complications due to unsafe abortions fell by a third, according to the Guttmacher Institute, which also says that the use of the drug misoprostol “became more common throughout the region” and “appears to have increased the safety of clandestine abortions.”

Feminist innovation? It was Latin American feminists who first learned, in the early 1990s, that misoprostol was effective and safe for terminating pregnancies. Today, this drug is recommended by the World Health Organization and approved by health authorities in many countries.

They also launched a global day of actionnow International Safe Abortion Daya day of struggle that is observed around the world on September 28.

But There’s More to Do

However, despite these significant advances, millions still live in a horrendous reality. Abortion is completely banned in the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Suriname. In El Salvador, women can face up to 50 years in prison if they have a miscarriage or a stillbirth.

In Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela, abortion is allowed in limited circumstancesmost commonly when the health or life of the woman is at risk. Belize and Bolivia also take into account financial and family hardship and, along with Brazil and Panama, rape and severe fetal abnormalities.

Raped girls and women are forced to give birth in the countries with total abortion bans, but also in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela. In Ecuador, where the parliament recently approved abortion in cases of rape, the president Guillermo Lasso just partially vetoed the bill.

There seems little hope of any change to abortion restrictions in Central America, but the next big win could come in the region’s most populous country, Brazil, with its 212 million inhabitants.

Abortion is only permitted in cases of rape, fetal anencephaly (a severe brain and skull defect), or if the women’s health is at risk, and the practice is hampered by the far-right government of Jair Bolsonaro, which mobilizes groups of fanatics to harass women and health personnel. But Brazil has elections this October, and the current frontrunner, former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, recently said he would be in favor of legalizing abortion.

As Causa Justa’s González said, there’s no full democracy when half of the population has no right to decide about their bodies and their livesand criminalizing abortion does exactly that.

This is, in short, a battle for freedom and full-blown democracy.

On the other side of this battle, there are powerful and coordinated attempts to roll back hard-won sexual and reproductive rights, not just in the Latin American region but across the world. This backlash includes well-funded, international networks to misinform and manipulate women and to promote unproven and potentially dangerous practices, including a “treatment” to “reverse” medical abortionsboth revealed by openDemocracy investigations.

There are also armies of lawyers trained and paid for by international conservative groups to litigate or lobby against women’s rights. Those are the groups that drew up a carefully drafted agenda to end the constitutional right to abortion in the United States.

It looks increasingly likely that the anti-abortion movement will succeed there, forcing U.S. women into a frightening world of backwardness, persecution, and unsafe, clandestine abortionsa world that their Latin American sisters have experienced for decades.

But, at the moment at least, in Latin America the anti-abortionists are losing. And we are winning.

Diana Cariboni is based in Uruguay and started writing for Tracking the Backlash in 2018. She is now our Latin America editor, coordinating our investigative reporting in the region. She was previously co-editor-in-chief of the IPS news agency and led its Latin America desk for more than ten years. She wrote the book Guantánamo Entre Nosotros’ (2017) and won Uruguay’s national press award in 2018. Follow her on Twitter (@diana_cariboni). Contact her at diana.cariboni@opendemocracy.net with tips for new stories in Latin America.