Seven days a week, Vera sits at a fold-out table outside a no-frills boteco in Botafogo, a neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro’s well-off South Zone. Throughout the day, a trickle of people come up to her and hand over cash. They are placing bets in a popular lottery game called jogo de bicho. Vera punches some numbers into a little black machine and hands over a receipt. The whole transaction takes place in public, but both the game and Vera’s job as an apontadora, or bookie, are illegal.

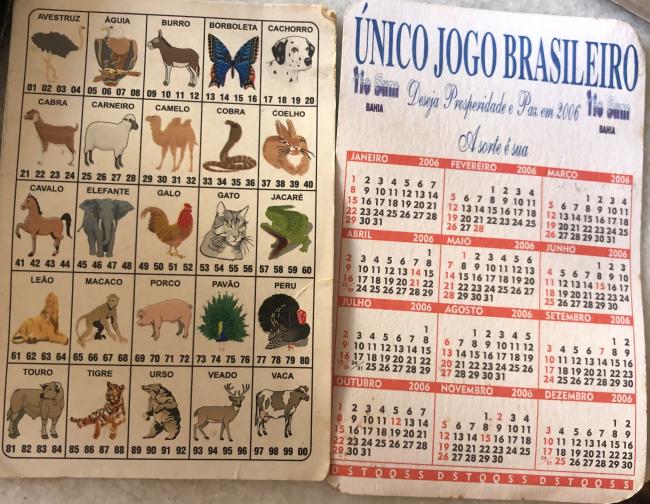

Jogo de bicho, which literally translates as “animal game,” was created in 1892 by João Batista Drummond, a baron who owned Rio de Janeiro’s first zoological garden. Seeking to attract more visitors to his zoo, Drummond started handing out a coupon with a picture of an animal to anyone who bought an entrance ticket. At the end of each day, the baron would draw the picture of one animalfrom a possible 25out of a wooden box placed by the zoo’s entrance. Visitors with the winning animal took home some prize money, worth more than a carpenter’s monthly salary at the time.

The game rapidly evolved into a numbers game and spread across Rio de Janeiro and Brazil. Its transformation from zoo raffle to a popular and profitable lottery was “uncontrollable,” says Michel Misse, a professor of sociology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). The outlawing of the game shortly after its creation did nothing to stop its expansion and popularity. It is widely played in Brazil still today.

A Twilight Zone

Besides the state-sponsored lottery games, gambling is illegal in Brazil and has been since 1946. But while casinos, for example, saw a “golden era” in the 1930s and 1940s, jogo de bicho has been criminalised by the Brazilian state almost since its invention in the 1890s.

“The only game that was never legal in Brazil was jogo de bicho,” says Misse. “By the time gambling was made illegal [in 1946], jogo de bicho was already entrenched and popular.”

Its popularity, combined with the complicity of the police, has allowed the illegal game to thrive for well over a century. Police officers are bribed to let the game function unperturbed, but these bribes are just an extra incentive to ignore an activity they already tend to regard as harmless. “The policeman’s mother played, his mother-in-law played, his sister played How was he going to crack down on jogo de bicho?” says Misse.

The game has long existed in a twilight zone, technically illegal but operating out in the open with little fear of reprisal.

Danilo Freire, a political scientist at the University of Lincoln in the UK, notes that jogo de bicho and bicheiros’ other activities are an important source of employment for the low-income segments of the population. Involvement in the game has always been prosecuted as a minor offence, not a crime. These factors have all contributed to jogo de bicho being generally accepted as an innocuous and even quaint feature of Brazilian society.

This ignores the fact that the game rests upon a violent criminal structure, says Vera Araújo, an investigative journalist who covers public security issues in Rio de Janeiro. “Behind the apontador, behind the people placing bets on the numbers, there is a whole mafia, there are very serious crimes, there are homicides,” she says.

Crime and Carnival

Jogo de bicho’s current structure emerged in the second half of the 20th century; as the game became more profitable and the trade behind it turned more violent, it became concentrated in the hands of a few bosses, the bicheirosalso known as banqueiros (bankers), as it is they who bankroll the winnings.

These bosses exercised territorial control over the game and other illegal gambling activities, such as slot machines and casinos. The nature of their business meant that as well as buying off the police and local authorities, they contracted death squadsoften made up of off-duty or retired policemento guard their gambling spots and act as their personal security detail. Bicheiros are known to be involved in a variety of crimes, including murders and executions as well as corruption and money laundering. But efforts to investigate and prosecute them have often proven unsuccessful, testimony to the wealth and power of these criminal bosses.

And yet, “a bicheiro is not [seen as] a criminal, he’s a minor offender” says Araújo, who blames Brazil’s legislation. The involvement of bicheiros in popular cultural sectors, notably football and Carnival, also helped them maintain a cleaner public image. “From the 1970s onwards, bicheiros were making lots of money, and they started expanding their business. Not so much to make a profit, but to launder their money and buy the support of the local community,” Freire says.

Castor de Andrade, one of Brazil’s most famous bicheiros, did this better than anyone. He embodied the image of the popular yet feared bicheiro who moved seamlessly between the criminal underworld and Rio de Janeiro’s high society. Andrade was the honorary president and main backer of Rio’s Bangu Atlético football club and patron of the Mocidade Independente de Padre Miguel samba school. He helped found the Independent League of Samba Schools (Liesa) in 1984, an organization that is widely known for being a legal façade for bicheiros and that dominates the Carnival samba parades in Rio to this day. Present-day bicheirosusually the sons and grandsons of the capos from the 1980s and 1990scontinue to be involved in samba schools and Carnival, although they now keep a lower profile.

Most researchers concur that the power of bicheiros has passed its peak, weakened by power struggles between their descendants, attempts to crack down on money laundering and corruption, and competition to the jogo de bicho from other forms of gambling, such as online betting. But Vera the apontadora says that she has not noticed a change in the number of people playing over her 30 years collecting bets in Botafogo.

“[The game] is very traditional,” she explains. “And trustworthy!” she adds. “It is the most honest thing that exists. You win ten thousand, you receive ten thousand.”

Legalization on the Horizon?

This “honesty,” carefully cultivated by bicheiros over the game’s decades of endurance and rendered possible by its existence beyond the reach of the taxman, might soon be put to the test: in February, Brazil’s lower house of congress voted to approve a bill which would legalize gambling, specifically casinos, commercial bingos, and jogo de bicho.

There have been various attempts to make gambling legal in Brazil, but these have always come up against the moral objections of the powerful religious lobbypreviously the Catholic Church, today the neo-Pentecostals. The current attempt could still be blocked by the Evangelical lobby, as the bill must be approved by the senate and sanctioned by the president of the Republic to become law.

Were the bill to be passed into law, it would be tricky to enforce. If applied correctly, the law would upset the codes that currently govern the game, notably its territorial division between different bicheiros. The bill’s specification that anyone managing the jogo de bicho must have a clear criminal record would in theory exclude most of the current bosses from bidding for a license to operate the game.

“They would just employ people as a front, to represent them,” says Araújo, who believes bicheiros are in favour of the game being legalized as they would no longer have to pay such large bribes to the police and other public officials to keep their business going. There have been other indications that the bicheiros support the legalization of their trade. Lawmakers with known links to the game’s bosses have pushed for legalization in the past, while bicheiros have invested in hotels which could house casinos if and when these are made legal.

On the flip side, if the game were legalized bicheiros would lose part of their earnings to the tax authorities, as well as face the risk of competition from foreign investors.

The UFRJ’s Misse concludes that bicheiros want the game to be legalized “if they are the ones who can exploit it legally. And there are no guarantees to this.” Misse believes that if the bicheiros are forced out of a legally-run jogo de bicho, they will continue their operations in the shadows. “It is perfectly possible to imagine that congress legalizes jogo de bicho, and that the game continues in a clandestine way.”

Constance Malleret is a French and British freelance writer based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. She covers Brazilian politics, business, and social and environmental issues.