Leer este artículo en español.

GUATEMALA CITY. Amid unprecedented legal actions against the electoral process, Guatemalans will head to the polls on August 20 in the most consequential vote in the country’s recent democratic history.

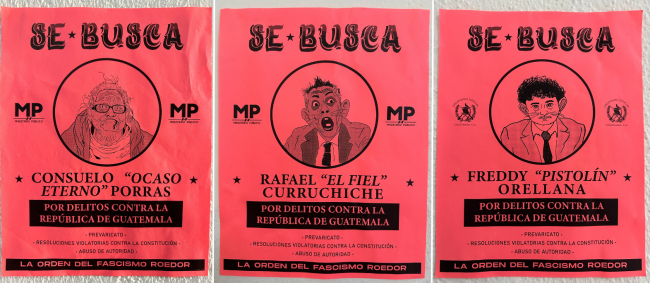

The presidential runoff pits progressive Bernardo Arévalo de León of the Movimiento Semilla party against Sandra Torres of the National Unity of Hope (UNE), one of Guatemala’s most enduring electoral vehicles. Immediately following Arévalo’s surprise showing in the June 25 first round, the public prosecutor’s office or Ministerio Público (MP) attempted to illegally revoke Semilla’s legal status. The multiple attacks aimed at derailing the second-round voteor the “extreme judicialization” of the electoral process, as the Organization of American States put ithas laid bare an ongoing technical coup d’état that seeks to undermine the popular vote.

The electoral cycle in Central America’s largest economy went from the ballot box to the courts, threatening to alter the constitutional order and create a climate of political and social instability even before the next administration begins.

According to Andrea Reyes, a lawyer and former student activist who won a seat in Congress with Semilla in the June 25 election, political elites have turned to these “desperate acts of intimidation given the overwhelming rejection of the status quo at the ballot box.”

“The ruling coalition does not want to allow citizens to freely choose their rulers based on the rational, logical, and even emotional arguments they deem appropriate,” Reyes says. “Not only has an open smear campaign been unleashed. Dangerously, state bodies obliged to defend the constitution have tasked themselves with undermining the certainty of the electoral results, putting the peaceful transition of power at risk.“

In the face of allegations of voter fraud, electoral fearmongering, and other elite efforts to hamper democracy, strong pronouncements from electoral observers, the international community, and different civil sectors of Guatemalan society helped uphold the first-round results and protect Arévalo’s spot in the runoff. According to recent polling, the upstart candidate is now projected to win. “But,” Reyes says, “the threat of destabilization and the criminalization of our movement will remain even after the second-round vote.”

Eight Years of Reconfiguring Counterinsurgent Governance

The administration of unpopular outgoing president Alejandro Giammattei and his VAMOS party will be remembered not as a series of mishandled state-building projects hampered early on by the pandemic but as the regime that prompted the worst deterioration of the rule of law since the return to democracy in 1985. Since Giammattei’s election in 2019, Guatemala has drifted toward authoritarianism with a marked destruction of judicial independence.

The criminalization of anti-corruption prosecutors in the last four years highlights the increased deployment of counterinsurgent governance tactics. The International Center for Journalists has recorded more than 750 attacks on journalists under Giammattei. Dozens of journalists, prosecutors, and judges have been forced into exile, while others have been entangled in expensive level battles or imprisoned. Harassment and intimidation campaigns have become prevalent online. At the same time, the mishandling of the Covid-19 pandemic created fresh avenues for government corruption, as the population bore the brunt of state inefficiency and a bungled vaccination campaign.

“We detect an institutional capture of the justice system,” says Carlos Mendoza, academic coordinator at Diálogos, an independent research cluster based in Guatemala City. “There is a virtual alignment of the three powers of the state aimed at dismantling public institutions to secure impunity through political and economic privileges, which has increased explicit expression of violence and repression, the militarization of civilian life, and an overall rise in social conservatism.”

Attacks on Guatemala’s democracy have escalated since the country’s landmark UN-backed International Commission against Impunity (CICIG) began to highlight ruptures in Cold War-era class formations. Launched in 2007, CICIG uncovered high-level corruption networks. Its investigations revealed that the country’s ruling coalition consists of a loosely connected group of well-established political elites, private sector leaders, organized criminal factions, and former military personnel that have easily come together around shared objectives: upholding methods of exploiting the state, safeguarding impunity from punishment or judicial accountability, and preventing any threats to the existing order.

CICIG’s exposure of multiple corruption schemes masterminded by the now-defunct Patriot Party, led by President Otto Pérez Molina and Vice President Roxana Baldetti, triggered notable anti-government protests in 2015. Both disgraced former leaders were stripped of their immunity from prosecution, forced out of office, and eventually sentenced for corruption.

“This turn of events led to a nationwide conversation regarding the elite networks entrenched in the Guatemalan public administration,” recalls Mendoza. “We now understand how historical stakeholders cling to power through the extraction of public funds without facing the consequences.”

Remedies Against Electoral Disillusionment

Coming just days after Pérez Molina’s resignation, the 2015 general elections occurred amid a “civil hangover,” as Rachel Nolan described in NACLA at the time. Jimmy Morales, a political newcomer backed by traditional elites, beat UNE’s Torres in a runoff. On the heels of the historic anti-corruption protests, disillusionment with the electoral offerings fed an understanding that real progress would have to wait until 2019. But the 2019 election was no different. As Rachel Schwartz wrote in NACLA: “Those who took to the streets to protest government corruption in 2015 and have patiently waited to reap the fruits of subsequent political reforms will have to wait a bit longer. Guatemala’s civil hangover’ has not yet lifted.”

Although hopes for improvement were low in 2019, the reality has been even more grim. Giammattei’s regime signifies an evident return to counterinsurgent practices, marking an inflection point in Guatemala’s 25-year peace trajectory. The outgoing administration’s policies steadily sent the country down an authoritarian path similar to that of many of its neighbors in the Western Hemisphere.

“The judicial system ceased to impart justice during this administration,” says Lissette Vásquez, a human rights advocate and legal expert. “The judiciary became a tool for enacting revenge, intimidation, and persecution against anyone who dissents, monitors, investigates, publishes, protests, demonstrates, or mobilizes against the abuses and restrictions to the freedoms and rights of citizens.”

According to Vásquez, strategies aimed at influencing the outcome of the vote also included the use of public resources for the official VAMOS party campaign.

Amid this adverse political environment, Arévalo and Semilla pitched discourses of hope versus fear, and change versus continuity, proposing reformist policies to revert increasing authoritarianism. Yet the progressive presidential hopeful barely registered in the pre-first-round polls, trailing behind Torres and fellow frontrunners Edmond Mulet and Zury Ríos. Arévalo’s underestimated centrist reformism flew under the justice system’s radar.

“Unsurprisingly, voters are extremely dissatisfied with the established political elite and have shown their discontent through the electoral process. Even though the ruling coalition tried to eliminate electoral challengers and manipulate the system in their favor, Arévalo and Semilla gained momentum,” explains Mendoza. “If Semilla were seen as a genuine contender, [Arévalo] would likely have also faced false accusations of electoral misconduct that could have prevented him from participating.”

From Anti-Corruption Movement to Anti-Corruption Party

Semilla originated as a political analysis and discussion collective in 2014 but gained significant momentum during the popular anti-corruption mobilizations in 2015. For Samuel Pérez Álvarez, who participated in those protests as a student activist and was reelected on June 25 for a second term as a Semilla party lawmaker, Arévalo’s unexpected first-round performance represents “the most popular rebuke since the 2015 demonstrations of the corrupt conservative status quo that has dominated the country for decades.”

Arévalo, 64, has served as a member of Congress as Semilla’s leader since 2020. Born in exile in Uruguay, he is the son of Guatemala’s first democratically elected president, Juan José Arévalo Bermejo, remembered for being the first popularly elected president after the 1944 Revolution in Guatemala. Current candidate Arévalo is a trained sociologist and a doctor in philosophy and social anthropology. He was ambassador of Guatemala to Spain in 1995 and 1996 and vice minister of foreign affairs in 1994 and 1995. Between 1984 and 1988, he was prime secretary and consul of the Guatemalan Embassy in Israel.

Winning Guatemala’s top office will require Arévalo and Semilla to beat one of Guatemala’s most enduring political parties. Represented by Torres, a former first lady and two-time failed presidential candidate, UNE boasts a formidable electoral apparatus that has previously benefited from illicit funds, according to prosecutors.

Torres made it into the presidential runoff in 2015 and 2019 but in both cases, she suffered substantial defeats against conservative opponents. “Conventional wisdom in Guatemalan politics suggests that anyone can defeat Sandra Torres in a runoff election,” explains Mendoza.

Despite UNE’s social democratic roots, Torres’s politics have become increasingly conservative. “We have seen a hard pivot towards social conservatism, with UNE aligning with the congressional alliance built around VAMOS and Giammattei in recent years,” says Mendoza. In her third presidential bid, Torres drafted an evangelical pastor as her running mate. Her platform leans heavily toward keeping abortion and same-sex marriage illegal.

According to legislator Pérez Álvarez, many Guatemalans view Torres as “an opportunist who changes her stance based on convenience.” A recent poll found half of Guatemalan voters view Torres unfavorably. “Her greatest strength and weakness lie in her control over a powerful political machinery, which enables her to secure votes in her rural strongholds but also tends to alienate many Guatemalans tired of corrupt politics as usual,” says Pérez Álvarez.

Torres’s campaign team did not respond to a request for comment.

Between Pessimism and Optimism

Román Castellanos, a Semilla lawmaker reelected in the June 25 vote for a second term in Congress, warns that the recent judicial maneuvers aimed at stripping Semilla of its legal standing are likely just the beginning of a larger campaign to undermine the growing movement.

“The MP has raided our offices as they try to find all possible arguments to wear down the party’s image and [attempt to] cancel our party,” Castellanos says. “We understand that, even if we were to win, we could not expect the persecution from the MP, FECI [Special Prosecutor against Impunity], and the courts to diminish.”

“We are facing a crucial moment in our history,” Castellanos adds, where legitimate elections stand as a “last defense against authoritarianism.” The thwarting of those election, he says, would allow unscrupulous and indifferent elites to “kidnap popular sovereignty.”

The 2023 Guatemalan election is breaking paradigms. Winning an election without being financed by corruption, drug trafficking, organized crime, or the robust private sector is possible. And political parties can be diverse, organic, and digital, not merely vehicles for electoral contention. “We are ready for a new era in politics,” maintains Castellanos. “This is an anti-corruption movement’s victory, channeling a rebuke of the system to reach the second round in Guatemalaand with the opportunity to win a mandate.”

Castellanos emphasizes that the choice is not just between two candidates. “August 20 goes beyond ideological or partisan attachments,” he says. “Instead, the ballot box offers us two diverging paths: embracing the current model or transitioning into a newer one.”

Vaclav Masek is a Guatemalan sociologist and graduate research fellow at the Center for Advanced Genocide Research at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. @_VaclavMasek / vaclavmasek.com