Read this article in Spanish.

Translated by Julianne Chandler.

In the Mayan highlands of Guatemala there is a summit called Alaska. Known locally as Chuipatán, it is located in K’iche’ territory at 3,015 meters (9,891 feet) above sea level. On Thursday, October 4, 2012, the cantones (districts) of Totonicapán occupied this and two other points on the Pan-American Highway to protest the high cost of electricity and the closure of the teacher’s college. No one imagined that the day would end with what many have called the first massacre by state forces since the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996. In a country that suffered one of the worst military campaigns against Indigenous peoples on the continent between 1981 and 1984, the Alaska Massacre brought back bitter memories.

Around 2:30 in the afternoon, two trucks and a pickup from the Guatemalan Army parked half a kilometer from the 5,000 protesters. They were carrying military riot gear and soldiers armed with Galil rifles. Community leaders, with their staff of authority or ch’ami’y, approached to dialogue with the troops but were greeted with tear gas. The soldiers began to fire their weapons. The unequal confrontation left six Indigenous men dead and 34 wounded that day. Subsequently a case was brought against a colonel and several soldiers, but it was later delayed due to various impediments. Each of the protesters had family and a place in their community. Their widows and orphans reclaim their lives and memory; these are some of the stories they told me.

Rafael Batz and Santos Hernandez Menchu

Pasajoc is a small village on the outskirts of the town of Totonicapán. Before the demonstration, Rafael Batz and the young Santos Hernández lived there with their respective families. Rafael’s house is surrounded by tall cornfields. Made of adobe, it has a tile roof and a wooden frame. Rafael was a mason. One of his last gifts to his daughters was to build rooms for them so they wouldn’t have to pay rent. Around the door he hung white flowers. He told one of them: “I’m going to plant you flowers here because I like flowers.” He called it “the garden of Eden.”

Rafael cultivated a small plot of corn. Like most K’iche’ families, Rafael knew how to string and weave textiles. With the money he bought firewood and additional corn to supplement his crop, and as well as the costly electric bills. In 1998, under the wave of privatizations in Latin America, the Guatemalan government sold the rights to distribute electricity. Monthly bills rose considerably in rural areas. The 2012 demonstration was a last resort after two years of schemes and failed dialogues between the Spanish company DEOCSA and the government. Rafael’s family was one among thousands that struggled to meet the payments each month.

In 1982, Rafael married Francisca. They met in Pasajoc and built their home there. The land “was his inheritance from his father,” recalls Francisca in tears. “We lived here for 30 years with my husband.” So they wouldn’t have to depend on men, Rafael taught his daughters to work and sow the land. “This is how they are going to do it,” Francisca recalls her husband saying. “This is how they will prepare the rows of milpas.” During his life, Rafael held various community positions: manager of roads and baths, school representative, member of the parents’ association.

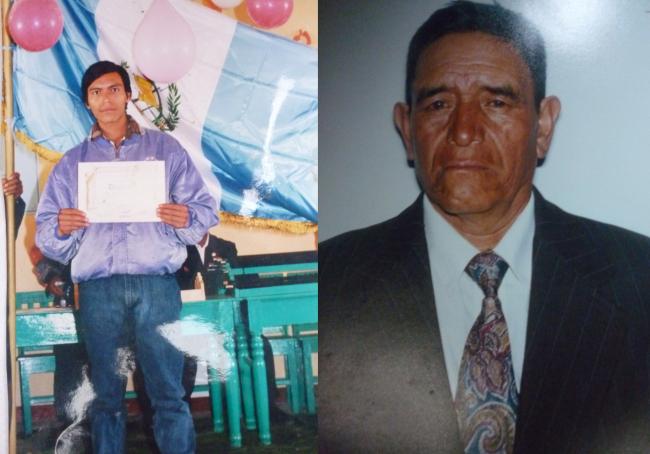

Santos was the youngest of the protesters who died on October 4. He was 33 years old. Santos received two Galil rifle shots: one entered through the left buttock and the other pierced his back, destroying his heart. At the time he had a 10-month-old baby with whom, according to his wife, he used to dance. “When he listened to music or I sang, whatever it was, he always danced. And since the baby already knew, she knew him, she would look at her father, and he started to dance.” The young couple had been married for two years.

In 2012, the government of General Otto Pérez Molina abolished the teaching school, one of the few employment options for thousands of Indigenous youth. With this policy, the privatization of education accelerated, along with the motive to look for a future in the United States. Santos worked as a bricklayer in the houses built with remittances from K’iche’ migrants. One of those migrants was his brother-in-law, a young man who had returned from the United States to invest in a sawmill. “He wanted to learn with me,” recalls his brother-in-law, “we had plans, but then he didn’t get to do it.”

The two men imagined the trip to the north together: “When I left I didn’t have a house and this is what I went for, my little piece of land that you can see from here to the river,” said Santos’s brother-in-law. “He would tell me, ‘Well yes, you went and did something. I’m going too, I want my house, I want my land. I also want to get ahead.'”

Eusebio Puac, Francisco Puac, Eligio and Jesus Caxaj

Eusebio Puac was born in 1979 in Chipuac, a village from which Mt. K’uxlikel can be seen. According to local legend, this was the site of the resistance camp led by the ancestors against the Spanish in 1524. Eusebio cultivated his milpa here. With his wife they had five children ages 17, 13, 10, seven, and a 10-month-old baby. After work, Eusebio assiduously practiced the trumpet, since he belonged to the brass band of the evangelical church Columna de la Verdad. On Mondays, Thursdays and Sundays they went to worship together. His wife Joaquina told me:

“E are’ keltib’iltab’ik, katotaj che uchak are’ kub’an estudiar ri trompeta”.

“He doesn’t go out, he finishes work and then he studies his trumpet.”

Eusebio’s father taught him the family trade. “When he started weaving, he was 12 years old. He started early, yes, as necessity compels us,” said Joaquina. In recent years the cost of materials had become more and more expensive, and it was impossible to make a living from weaving alone. When I met them in 2012, Eusebio’s family treasured the last corte (Indigenous skirt) that he had made before his death. They also kept his trumpet and the album of Christian hymns with which he learned the melody. The photo below reveals the deep sadness and mourning on their faces a month after the massacre.

Francisco Puac and his family wove for a merchant in Totonicapán. His wife, Celestina, talks about the intensity of the daily work routine: “He worked a lot! From seven to 10 or 11 at night.” They had been married for 25 years. In a corner inside the house, Celestina made a small altar with religious images and a photograph of her husband. Alongside the altar mother, son, grandfather, and sister-in-law gather to spin wool. In another room nearby, Francisco made his cortes. He was 42 years old when he died, and for at least 30 years he had worked on that same loom. His daughter, a cheerful and affable girl, lists the figures her father wove “He knew how to make a rose, a doll, a deer, a pine tree, a heart, a pansy flower, a basket, a tulip, a fish, and a quetzal.”

Chuimekena’ means “where the water is hot.” Francisco used to go with his wife to La Guaca, famous thermal baths in the town. His neighbors remember how Francisco helped Chipuac become recognized as a village. Sometimes, on Saturdays, the family would enjoy a “rabbit recadito and goat stew with herbs” while listening to marimba music from Explosión Musical. “My dad liked the songs ‘Una carta y una flor’ and ‘Flores pa’ mama’.”

Nearby lived Eligio Caxaj, an 80-year-old man, along with his son Jesús Baltazar Caxaj, daughter-in-law and three of his grandchildren. Every day his daughter-in-law brought him breakfast. Afterward, an intense workday began for Jesús Caxaj on the wooden loom. At noon he had lunch with the family and, at the end of the afternoon, “We warmed up coffee and ate bread,” says Jesús’s wife. Josefa met Jesús in a nearby chapel. They had lived together for 17 years. Weaving is not easy, Josefa explains:

“Stringing [the loom] cuts our fingershow the blood comes out! It’s hard to do, but as I told my husband: ‘I’m going to help you and we’ll find a way.’ I have to send our children to school, pay for food. There’s no money.”

Their young children attended school and the eldest was in his last year of the teacher’s college. Jesus was also a plumber, in charge of communal water. On the afternoon of the demonstration, Jesús was shot in the lower abdomen, causing a laceration to the iliac artery. He was 40 years old. Don Eligio could not bear Jesús’s death: “When he heard his son died, he simply couldn’t stand the sadness. On Thursday [my husband] passed away, Friday we buried my husband,” Josefa said. She continued, “On Sunday morning, my father-in-law died.” No one outside of Chipuac spoke of the death of Don Eligio in relation to the massacre, nor was he included on the lists of victims.

Lorenzo Vásquez and Arturo Sapon

During his lifetime, Lorenzo Vásquez was a farmer, weaver, soldier, and stonecutter. He was also part of the Water Committee of the town of Vásquez. He was born in 1971. As a young man he liked to play concertina. Lorenzo and his brother-in-law were soldiers in the Guatemalan Army. On two occasions he tried to get to Houston. As his daughter recalls, “He sold the land my grandmother gave him. He walked through the water [of the border river], he said. Sometimes he also made us laugh when he told us: ‘There were turtles in the water, so I left on the boat. And they caught me, so I came back here.'” The border police intercepted him in the attempt. When we met in 2015 his daughter was in first grade and his son, 10 years old, was in fourth grade.

During the demonstration Lorenzo was shot in the right and left arm, as well as in the leg. One of the perforations burst a vein in his right arm, complicating circulation. Lorenzo survived for another three years. Maura, his wife, remembers her husband’s pain:

“‘I have no spirit, I have nothing. That soldier took my feet and my hands. I saw it,’ said my husband. ‘I saw when the bullet came’and he crossed his arms’and it entered my hand.’ He did not feel, then, when the other [shot] entered his leg. He could not feel.”

Lorenzo was initially immobilized in a wheelchair and later suffered from pain that prevented him from working. Over time he became depressed. Lorenzo attended the Vida Nueva Evangelical Church to sing hymns. He died on September 7, 2015, from shots fired by the institution he once served.

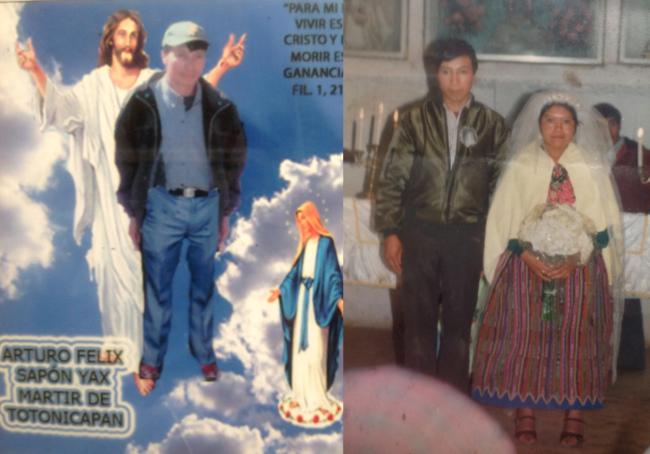

Arturo Sapon lived with his family in Panquix, a remote village where women herd black sheep and grow vegetables. He worked as a bricklayer and, after five o’clock, he played soccer with his brothers. Arturo had been married to Trinidad for 20 years. On the day of the massacre she spoke on the phone with him before the arrival of the soldiers. Little did she know that just two hours later the neighbors would return with Arturo’s body in a pickup. Hi daughters and the other widows sat frozen in a solemn silence when she recalled the experience:

“Oh God, qas ya no. Xinsetatik xinokloq. ‘Ay le wachajil’, xinche. Xinxukulej ri kik’ and ¡Jesus, ri kik’! Qas chila xinxib’ij wib’ and chila xinreq nuyab”.

“Oh God! No more. I ran. ‘Oh my husband,’ I said. I knelt on his blood and, Jesus, the blood! That scared me and I began to get sick.”

Four years later, Trinidad was still suffering from severe headaches associated with susto, a word used by the K’iche’s to refer to sudden upheaval and trauma. She frequently experienced insomnia. Her youngest son was also sick for several years: “Xaq iwab’, man k’ota utzil ruk ‘e xaq koq’ik,” she said. “He only stays sick, he’s not doing well, he keeps crying.” Arturo’s neighbors made a photographic composition in his honor: Arturo is standing in the sky, among clouds, and is received with open arms by Jesus and Mary of Nazareth.

A monument was erected in honor of the victims at the Alaska summit. One day the sun rose to reveal the monument destroyed by strangers, the names of Arturo and the others unrecognizable. This year a new one was built and the widows visited the cemeteries in the villages. The trial will resume in 2023 in the midst of a rather bleak panorama of cooptation of justice by businessmen and the military.

Recovering the memories of those who died at the Chuipatán summit is a way of reinscribing their stories; of uniting the broken pieces of the monument, of bringing fire and words together, something like what the ancestors of Chuimekena did five hundred years ago in the forests that surround Mt. K’uxlikel.

Sergio Palencia Frener is a sociologist, anthropologist, and writer. He is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at The Graduate Center, CUNY. He works on history, conflict, and resistance in Mesoamerica.