“If we look at it from the legal perspective, living here is a crime,” explained Susana Salazar, gazing out over snaking dirt roads, powerlines, and the patchwork of improvised homes that over 10,000 families call home. Salazar lives in Colonia Colosio, reportedly the largest squatter settlement in Mexico, which sits less than five miles from the Arizona border in Nogales, Sonora. “But, if we look at it from a humanitarian perspective, this is fulfilling a need.”

This needto adequately house a burgeoning population of migrants, deportees, and maquila workersis currently transforming Nogales’s urban landscape.

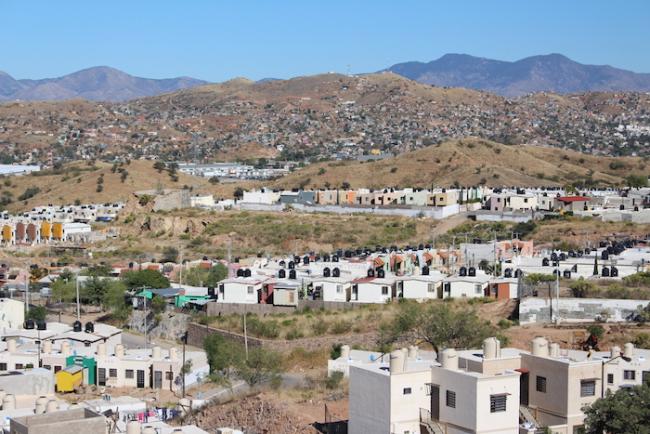

A massive concrete water tank sits on a hilltop at the edge of Colosio, near Salazar’s home. As one of the highest points in the area, this is a convenient location for a municipal water tank, but residents of the Colonia do not receive its waterinstead, most buy water at high prices from tanker trucks that prowl the neighborhood. The tank, meanwhile, supplies water to Las Bellotas, a subdivision packed with uniform row houses that nudge up against Colosio.

These urban developmentsand the challenges of living in themembody contrasting visions for a just and livable border city. Unfolding in parallel to the migrant detention and deportation crisis in Arizona, housing dynamics on the Mexican side of the border are another outcome of the free trade and immigration policies that have converged on the Sonoran Desert.

“Nogales has been growing like mushrooms, spreading out from the center and filling in any place it can,” explained Carlos Guzmán, an inspector in Nogales’s Department of Planning and Urban Development. Guzmán has seen his city explode in recent years with the rapid growth of the maquila low-wage manufacturing industry, and sprawling developments to house workers and migrants. Officially, the population of Nogales, Sonora, in 1960 was just under 40,000. By 2010, it had soared to over 220,000, though some estimates have it closer to 350,000.

Like the rest of the U.S.-Mexico border region, U.S. trade and immigration policy has been an important driver of this demographic explosion.The city was founded in 1884 as a waystation along the railroad connecting Mexico to the newly acquired U.S. territory of Arizona. Steam engines filled up on water at a spring surrounded by walnut trees nogales in Spanish.

Nogales’s population growth took off when Mexico instituted the Border Industrialization Program (BIP) in 1965, which incentivized U.S. manufacturers to set up factories on the Mexican side of the border. The passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 spurred further industrialization and population growth by phasing out all tariffs between the U.S. and Mexico. As a result, millions of peasant farmers who were driven off their land due to U.S. competition migrated north in search of higher wages. While many of these migrants crossed into the U.S., more remained along the border to work in factories or were deported back to Nogales.

Today, trade continues to flow through the same international corridor that the railroad initiated in the 1880s. Officials in Hermosillo, Sonora, and Phoenix, Arizona, are attempting to re-brand the transnational trade zone as the “Arizona-Sonora Megaregion,” to promote cross-border collaborations in industries such as aerospace, automobile manufacturing, and mining. As Samuel Arroyo, director of Nogales’s Department of Planning and Urban Development, put it, “We’re sitting on top of a vein of gold here.”

Socioeconomic inequality has been another ongoing factor shaping urban development throughout Nogales’s history. Powerful land-owning families have influenced decisions about the city’s growth, favoring development in its rugged western hills. According to Guzmán, “From that point, the city began to grow in favor of those who had the most power. A lot of the problems that we have with urban planning today are related to decisions that were made between the 1940s and the 1960s.”

The Kyriakis family is a case in point. Demetrios Kyriakis emigrated to Nogales from Greece in the mid-twentieth century, soon becoming a successful businessman and landowner. According to Guzmán, the Kyriakis helped attract the maquila industry to Nogales by selling land to developers. In 2006, the family inaugurated the Nogales Mall, with the aim of “modernizing the city” and anchoring a commercial district near some of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods.

The Kyriakis continue to shape a vision of Nogales as open for investment and tourism in short, a vision far removed from the daily experiences of the majority of Nogales residents. The United Nations and several Mexican government agencies recently ranked Nogales ninth among 152 cities nationally in an index of prosperity. The ranking took into account the city’s ability to attract investment and to promote the growth of jobs and housing construction. But, according to official 2010 statistics, 34 percent of Nogales residents live in poverty and another 5 percent in extreme poverty.

As systemic forces funnel migrants from other regions of Mexico and Central America toward Nogales in search of a better life, a market for low-income housingboth formal and informalhas been booming. Local landed elites and housing companies from other parts of Mexico are developing subdivisions to profit off the increased demand. At the same time, with votes and access to labor on the line, both the municipal government and the maquila industry have tried to influence housing policy.

With so many powerful competing interests at play, Nogales’s housing does not always meet the needs of migrants and factory workers, according to Juan Rábago, an architect in the planning department. In many subdivisions, or fraccionamientos, he explained, homes are built cheaply with little thought for quality of life. As he drove through one of the Kyriakis’ subdivisions called California, he pointed to areas of “green space” that amounted to little more than dry grass and litter. “The Kyriakis don’t care about Nogales. All they care about is making money,” added another planner in the department, who asked not to be named. The Kyriakis family company did not respond to our request for an interview.

Nogales is not unique in that housing for its poor and working class has become profitable for investors. Construction and finance sectors across Mexico have profited from a booming “affordable housing” industry. As political scientist Susanne Soederberg has charted, a complex network of public and private institutions extends housing loans to new populations while providing massive subsidies to construction companies. Mexico’s mortgage industry, she argues, increasingly follows the U.S. model that helped tank the global economy in 2008.

On face value, the resulting homes satisfy Mexicans’ right to housinga basic human right enshrined in Article 4 of the country’s constitutionbut they are often tiny, poorly constructed, and inconveniently located. La Mesa, for instance, is a residential development 13 miles from Nogales’s center and a relic of pre-2014 federal housing law, when the development of new land was on city outskirts. For La Mesa’s residents, the long commute for work, healthcare, or other daily business has caused some to move away from the fraccionamiento, as evidenced by its high rate of abandoned homes.

One proposed solution to La Mesa’s isolation is currently taking shape. In August 2016, construction began on a 70-hectare industrial park to generate jobs for La Mesa’s 5,000 families. At the groundbreaking, developer Antonio Dabdoub relayed his vision, that “the growth of housing and of the maquila go hand in hand” and that the industrial park would “support all the people who live here and that it be like a big family.” According to Arroyo, director of the planning department, “this action will help mitigate the sense of isolation that people feel there.”

Beyond concerns with livability, the requirements of loans and federal housing subsidies still exclude millions of low-income Mexicans from even entering the affordable housing market. The Mexican government touts INFONAVITits federal housing credit program for the working classas “the main Mexican state institution for ensuring that families can exercise their constitutional right to decent housing,” citing that the program grants seventy percent of home loans issued nationwide. Yet, given the insecurities of factory work and often-transient nature of border populations, many Nogales residents cannot afford the monthly pay-in which can be as much as 30 percent of their salaryor provide required evidence of steady employment. Such dynamics also contribute to the rates of abandonment in La Mesa, where many of the houses are financed through INFONAVIT.

Low-income housing developments are often envisioned as a utopian alternative to informal settlements like Colonia Colosio but the results are often far off from their idealizations. For the urban planners and architects who work under Arroyo in the planning department, the way to meet the housing needs of nogalenses is through regulation of building codes and collaboration with developers. “Everyone has a right to Nogalesthat is the vision that we have,” explained Arroyo. He added, “But, if we don’t prepare, we’re going to keep growing in anarchy.”

Indeed, visions for the city’s future often take on an idealistic quality. A case in point is the Lisboa development, which replaced an abandoned mall, a space where Rábago from the planning department recalls neighborhood kids going to smoke. In contrast to neglected spaces that he said attract “delinquent activity,” Lisboa is organized to promote healthy, productive, engaged citizens, with its neatly ordered streets, manicured public spaces, and homeowners’ associations.

According to Alma Quetzalli Tolano, an architect from the firm that designed Lisboa, living in one of their subdivisions requires a cultural adjustment. “Many people comment that our houses are too small, but when you ask them where they lived before, they usually come from the country we need to teach them the culture of how to live in a place like this.”

Centauro de la Frontera, a housing project approved in 2010, was hyped as an innovative solution for addressing informal urbanization. The project was set to contain 22,000 low-income houses, as well as schools, clinics, shops, and parks. In the words of Mexico’s then-Secretary of Social Development Heriberto Guerra, Centauro would “modify the paradigm of life of those living in irregular zones.” Uniradio Noticias called it, “the first step in the Nogales of the future that is better organized and better urbanized.”

What came to pass was much different. The project fizzled after a series of scandals, most notably, the disappearance of 29 million pesos roughly 1.6 million dollars – designated for infrastructure projects under Mayor Ramón Muñoz (2012-2015). Employees of current Mayor Cuauhtémoc Delgado’s administration wear neon green t-shirts emblazoned with a cartoon rat decrying the previous administration’s fiscal delinquency.

Whether or not low-income fraccionamientos can serve the same populations as informal settlements is debatable. For some factory workers, it might be a question of preference, but for others particularly recent migrants the price point and mortgage requirements of the most affordable subdivisions are unaffordable.

For those who do choose life in a low-income subdivision, informal adaptations help make the homes livable. At every turn in fraccionamiento Las Bellotas, which abuts Colonia Colosio, there is evidence of the tiny homes’ transformation to better suit inhabitantsextra rooms added to a house, or an entryway converted to a small shop. Along the main road, residents have painted murals to provide character to the neighborhood’s otherwise planned uniformity.

Such modifications technically violate the rules of the planning department, but inspectors like Guzmán recognize that such alterations come from a place of necessity. “Developers have adapted these homes to the price needs of the common family, but in terms of size and design, they’re not adequate,” he admitted.

In 1995